You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Older athletes: time to go ballistic!

How can older athletes maintain speed and power as they age? Andrew Sheaff looks at new research on ballistic strength training

How can older athletes maintain speed and power as they age? Andrew Sheaff looks at new research on ballistic strength training

As dedicated athletes, we’re often focused on our peers and making sure we’re doing what we can to be competitive. However, there is another opponent that we tend to overlook, an opponent we ought to be spending a lot more time focused on. That opponent is Father Time. Beyond the obvious implications for health and longevity, the process of aging can really compromise your performance!

Power losses

While it’s commonly understood that muscle mass and strength decline steadily as the years pass, it’s less appreciated that relatively, muscle power declines significantly faster(1). If speed and power are important to your athletic goals - and they are in just about every endeavor - it’s critical to do anything and everything possible to maintain those attributes. The good news is that it’s been shown that power training, where resistance training is performed at high speed, is reasonably effective at mitigating or even reversing these losses, particularly in the general population(2).

However, the aspiring athlete doesn’t want an adequate solution; he or she wants a highly effective solution. To maintain the speed and power outputs required for successful athletic participation, activities that produce the greatest neuromuscular activation are needed. While moving loads quickly produces benefits, what would happen if loads were moved so quickly that they were actually released? What would be the impact on neuromuscular activation? Fortunately, these very questions have been subjected to scientific study, and we now have answers that can be applied to improve sporting performance.

New research

A group of British researchers decided to investigate the impact of three different styles of strength training execution on neuromuscular activation(3). Twelve recreationally active older males were included in the study, and the average age of the participants was 67 years old. The subjects performed repetitions on a hip sled (see figure 1) at loads equal to 20, 35, 50, 65, and 80% of the maximum load. At each load, the subjects performed repetitions three ways:

- With a controlled velocity.

- Repetitions as a fast as possible in a non-ballistic manner.

- Repetitions as fast as possible in a ballistic manner where the sled was released.

The researchers then measured power output, force output, velocity, rate of force development, and muscle activation of the knee extensors, hip extensors, and plantar flexors during each repetition.

Figure 1: Hip sled machine

A hip sled has a triangular frame constructed using heavy gauge steel, which reclines at an angle to accommodate several different exercises. A roller allows a weighted pad or ‘sled’ to slide up and down the front of the frame. In the ballistic reps, the subjects accelerated the sled fast enough so that they actually launched themselves – ie contact between the feet and the base plate was broken.

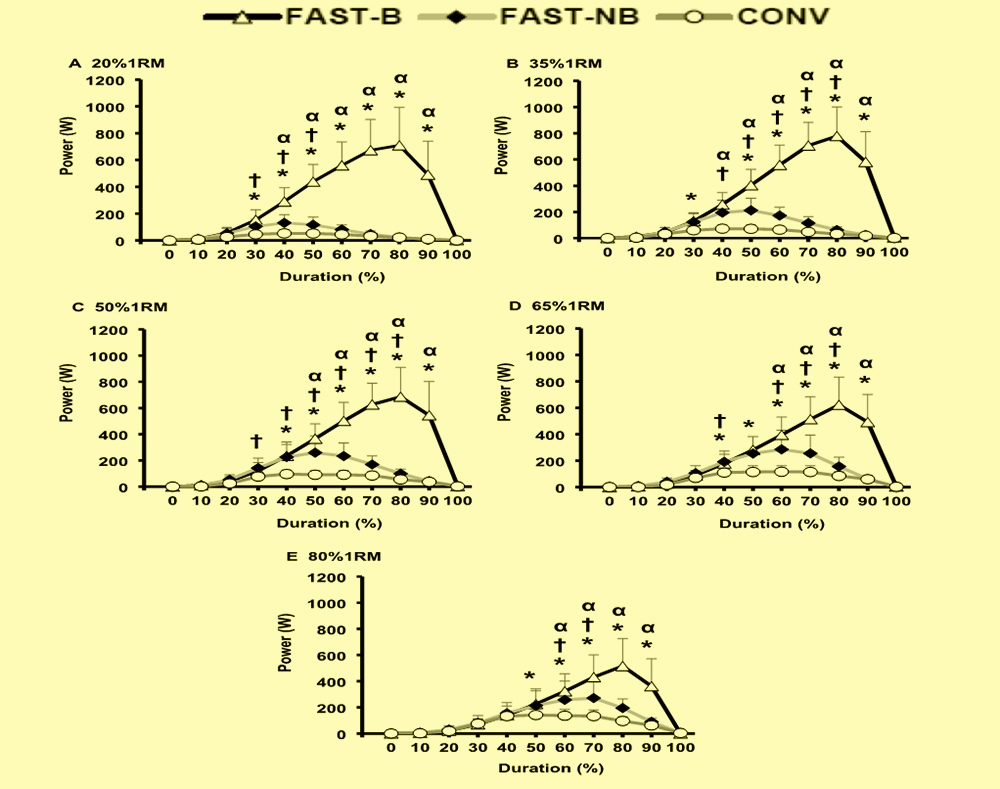

The results were overwhelming in their implications. For just about every measure of neuromuscular activation, the ballistic repetitions significantly outperformed the other contraction types. There was more power output (see figure 2), more force output, higher velocity, superior rate of force development, and greater muscle activation of the knee extensors and hip extensors. Performing repetitions in a ballistic manner produced significantly greater neuromuscular activation compared to fast repetitions or controlled repetitions. What’s also interesting is that while there were some differences in neuromuscular activation across different loads when performing ballistic activities, these differences were relatively small. In a nutshell, it seems that the load you use if of secondary importance when compared to how the repetitions are performed!

While power, velocity, and speed were similar between the ballistic and fast non-ballistic reps during the initial phases of the movement, it was during the latter portion of the repetitions that the differences became pronounced. Because the intent was to throw the sled ballistically with the legs, the subjects had to continue to produce power throughout the full range of motion to continue to accelerate the sled. If they failed to do so, the sled would not have achieved enough velocity to be released. The additional force that was required likely lead to the greater muscle activation of the legs.

What should be noted in addition is that the ‘fast’ contraction style, where the subjects moved the loads as fast as possible without releasing them, was also superior to the standard contraction style in almost every test. This re-affirms previous research highlighting the value of power training. Clearly, moving the resistance quickly is a superior option as compared to moving the resistance in a slow manner.

Use it or lose it!

While aging is inevitable, the impact of aging can often be mitigated by what we choose to do. When it comes to maintaining high force outputs, in particular high force outputs at high speed, practicing these same activities ensures that we can continue to create high levels of force as we age. Unfortunately, these are some of the first types of training that older athletes tend to stop including in their preparation. As the study results indicate, the solution is simple- start throwing your loads!

Figure 2: Power outputs using ballistic, fast non-ballistic and slow smooth reps

Clear triangles = ballistic reps; black diamonds = fast non-ballistic reps; clear ovals = slow smooth reps. At every loading intensity (% 1RM), the ballistic reps resulted in far higher power outputs towards the end of the rep.

It’s understandable if you don’t have access to a weighted hip sled that you can use to launch yourself as the subjects did. Likewise, it’s probably not safe or effective to start throwing around dumbbells or barbells! Fortunately, there are plenty of low cost, easy to implement solutions. For the lower body, any sort of jumping, skipping, or hopping would fit the bill. With these activities, you’re literally throwing yourself into space. These exercises can be done anywhere with no equipment. Simply start with very basic variations performed at controlled intensities, and then progress from there. Over time, you can begin to use more advanced exercises such as depth jumps or sprints, and perform that at higher and higher speeds.

For the upper body, any sort of medicine ball throw would be excellent, not worrying so much about the weight of the ball. You can perform these throws against a solid wall or with a partner. Another simple introductory option is to lean against a wall in a push-up position and throw yourself off the wall. You could eventually progress to use a bench, and then to the ground. As noted above, the percentage of maximal load played less of a role in determining the neuromuscular activation than did the intent to move ballistically. Medicine balls and bodyweight will get the job done.

If you haven’t been performing any sort of high velocity training, it may be worth starting slowly, by focusing on performing the concentric portion (the part where the muscles contract) of your strength training with greater speed. For the majority of the tests that were performed, high-speed, non-ballistic strength training movements created more neuromuscular activation than smooth and controlled strength training. Performing strength training exercises with a fast concentric movement will create an excellent foundation for eventually performing ballistic motions.

References

- Ageing Res Rev. 2017 May;35:147-154.

- J Strength Cond Res. 2014 Mar; 28(3): 616–621.

- Eur J Appl Physiol. 2022 Apr 16. doi: 10.1007/s00421-022-04947-x. Online ahead of print

Related Files

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.