You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Pump your lactate shuttle: make lactate your friend, not foe!

One of the greatest training innovations in the last fifty years has been the realisation that lactate plays an important role in endurance training, and that training at or near your ‘lactate threshold’ pace (the speed at which your blood lactate levels start to rise sharply) can improve overall speed and endurance.

In a recent article, we looked at the science behind this, examining how lactate metabolism functions and how to find your own, personal lactate threshold (see here: spb.affino.com/training/training/tame-your-tempo). We also discussed two ways to use this information in training: steady-pace ‘tempo’ workouts (in which you run the whole way at or near lactate threshold), and ‘predator runs’ (in which you start slowly then speed up, passing through threshold pace in the process). Both are useful, proven techniques.

But there is an emerging array of new methods, also lactate-based, but very different from traditional tempo or predator workouts. Doing these, you don’t work out at steady or gradually increasing effort levels; instead, you alternate through cycles of fast, not-as-fast, fast, not-as fast. That sounds rather like traditional interval training. However, these aren’t intervals as most people understand them, because the not-as-fast portions are too brisk to be true recoveries. Rather, it’s something one of its architects, British coach Peter Thompson (now residing in Eugene, Oregon, USA) has dubbed “new interval training(1).”

The lactate shuttle

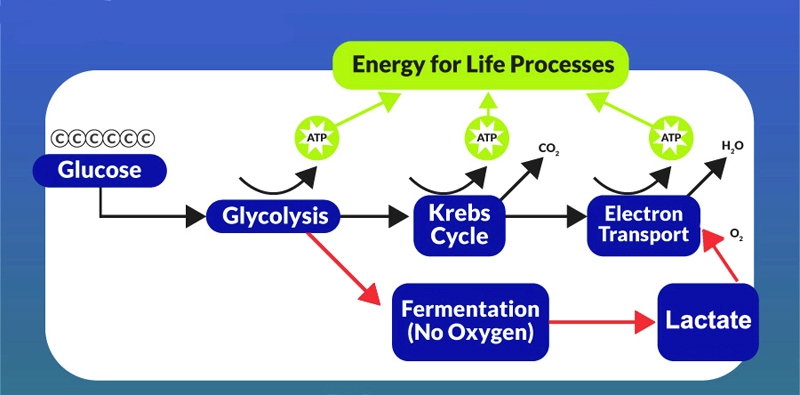

The key to the new approach is the discovery of something called the lactate shuttle. Spearheaded by research done at the University of California, Berkeley, in the late 1990s by exercise physiologist George Brooks(2-4), this type of training begins by asking a previously overlooked question. Blood lactate rises with exercise – something known for decades. But is this actually a sign of the muscles starting to break down into irrecoverable fatigue? Or could it actually serve a purpose?Brooks’ answer was the latter. When lactate levels climb, he found, the body uses the blood to carry it from the hard-working muscles that are producing it to better-oxygenated places where it can more easily be used (see figure 1). One of these is the brain(5). Another is the heart. The arms and other lesser-working muscles also appear to be able power themselves with lactate pulled from the blood, saving glucose for the muscles that really need it. Even the liver gets in on the act, using its own oxygen supply to rebuild lactate into glucose to be shipped back to the muscles(6). (The lungs, on the other hand, are probably working hard enough to be net producers of lactate, rather than consumers(7).

Figure 1: The lactate shuttle and energy production

When oxygen is plentiful (ie during lower or moderate intensity exercise), muscles derive energy through the aerobic energy pathway (top). During intense exercise (when glycolysis rates are very high), more reliance is placed on the red pathway, leading to lactate accumulation (bottom right). However, this lactate can be broken down for energy via the ‘lactate shuttle’ pathway (the rightmost red arrow) providing plentiful oxygen is available. The body achieves this by transporting lactate from working muscles to regions of the body where oxygen levels are higher.

The result is to make the body more efficient at running, pedalling, rowing, or otherwise going harder, faster, longer. Glucose is the body’s ‘high-octane’ fuel. The lactate shuttle helps ensure that it goes where it’s most needed. “It helps establish a hierarchy for glucose use,” says John Halliwill, an exercise physiologist at the University of Oregon. “The organs that most need it get priority and the others rely on lactate.”

Mixing it up

A more efficient lactate shuttle may be a key to better performance, and one way to improve your lactate shuttle is by varying your pace so that it is sometimes slightly faster than lactate threshold, and sometimes slightly slower. A similar method has been used by Italian coach Renato Canova, who has worked with some of the world’s best Kenyan runners. This, in fact, is the gist of Thompson’s ‘new’ interval training (although the primary thing that’s new about it is the understanding of why it works, and from that, how to optimise it).Two of the greatest runners of 1970s did something very similar. America’s Steve Prefontaine (see figure 2), who at one time held seven US records at distances ranging from 2000m to 10,000m (then died young in a car crash) was famous for a workout now known as Pre’s 200s’ in which he alternated between 30-second 200s and 40-second 200s for as long as he could. It sounds deadly until you realise that Pre was a 3:54 miler (about 29 sec/200m), and that 40-second 200s equate to a 33:20 10K, more than 50 sec/mile slower than Pre’s 10K best. In other words, he was running his recoveries at, what for him, might have been 5 seconds/lap slower than marathon pace, had he ever run a marathon. What’s stunning is that he was able to maintain it for a whopping 18 laps (4.5 miles) - a record that held until 2008, when Galen Rupp extended it to 24 laps, which is just shy of 6 miles.

Figure 2: Steve Prefontaine

Another version of this was practiced by Australian superstar Robert de Castella (figure 3), who, among other things, lowered the marathon world record to 2:08:18 in 1981. His version was to run 400m at 1-2 seconds per lap faster than his 5km pace, then ‘pseudo-recover’ at about a minute per mile (8 seconds per 200m) slower. After the pseudo recovery, he’d go right into another fast 400m, continuing the process for 12 laps (4,800m).

Figure 3: Rob de Castella

The key to both of these are the brisk recoveries. A lot of coaches - myself included - like to call them floats. “Float, don’t jog,” is what I tell people. Thompson prefers the term “roll-ons” because you roll on from the faster part of the cycle into a still-brisk pace. Whichever term you prefer, the idea is that these recoveries are brisk. If you get them right, you’ll spend the first two-thirds of the float watching the start of the next speed bout 100m closer, wondering how you’ll ever be recovered enough to speed up again. Then, in the last few meters, you’ll discover you can actually do it.

Magic in the float

The new science by Brooks, Thompson, and others has produced a theory for why it works, and with it, insight into how to fine-tune Prefontaine and De Castella’s decades-old methods. Brooks’ studies suggest that the ‘magic’ in this type of training comes from the float, not from the higher-intensity work that preceded it. The primary function of the fast parts of the workout, it turns out, is simply to work you hard enough to cause your blood lactate to rise. Once that has happened, you transition to the float. This trains your body to clear lactate efficiently, while still running at a brisk speed - though not so brisk that you are still accumulating lactate. In other words, what you are training is the lactate shuttle.

There is no single best way to do this. Rather, it varies with your goals, personality, and, ultimately, inventiveness. Prefontaine did it by running really fast 200s—fast enough to quickly build up a surplus of lactate then following them with recoveries that were a full 33% slower. It’s the equivalent to someone with a 5:50 mile PB doing the fast 200s in 45 seconds and the floats in 60 seconds. It looks superhuman only because Prefontaine was fast, and because he could hold it for such a long time. De Castella ran a higher fraction of his workout at the fast pace, but kept the pace slower. That allowed him to recover from 400m speed bouts in only 200m, rather than having to run a full 400 before he was ready to speed up again.

Alberto Salazar once told me that back in his prime, he used to do something similar, albeit with longer repeats. His workout alternated miles at 10 seconds faster than marathon pace (probably quite close to his threshold pace) with miles at about 20 seconds per mile slower than marathon pace. His goal was largely psychological; a long series of such repeats, he said, made marathon pace feel comparatively easy. But years before Brooks discovered the lactate shuttle, he too had also found a pace-varying speed workout that, although quite different from Prefontaine’s and De Castella’s, was probably working the same physiological processes.

Pacing the float

Scientifically, the goal is to run the float briskly, but not too briskly. It has to be slower than threshold pace, or you’ll continue to accumulate lactate, rather than training your body to clear it. But it shouldn’t be too slow, or it won’t train your lactate shuttle to use that lactate efficiently when you’re working hard. Finding the right pace is fairly subjective. The key thing is not to slow to a walk, or even a jog, the moment you hit the end of the fast repeats. If you’re schooled in conventional intervals, this will be hard, because in them, the goal is to recover as quickly as possible. Here, the goal is to keep moving. I tell people to ‘trust the recovery to come to them before the next repeat begins’. If it doesn’t, it’s probably the repeat that you did too fast, not the float.

If you’re really determined to check your watch, another metric is that as you start this type of training, your floats will be fairly slow. As you both learn the method and get fitter, they will speed up. When you are truly fit, your floats may be as little as 4 seconds per 100m slower than your speed bouts - little enough that people watching you may not be able to detect them without a stopwatch.

Practical advice for training sessions

Once you understand the science, there are a nearly unlimited number of ways to put it into practice. Here are a few:

- Sets of 300-300-300-300-s. The hyphen here is a 100m float, so this workout is a set of four fast 300s, each followed by a 100m float. (Note: the last 300 is also followed by a float; the floats are where the lactate-shuttle training occurs, so all such workouts end with a float.) Run the 300s at somewhere between 5km to 3km pace. Between sets, do an easy 400m recovery. The total number of sets should be about the same as you’d do for traditional 1200m repeats (possibly one less, since the 100m floats can add up). You can also do this as sets of 300-300-300 (which might be easier first time).

- Patched-together miles. These are like the 300s, but with longer segments. For example, you could do sets of 600-400-600-. Pace the fast parts no faster than your 5km pace. Note that counting the floats, these sets actually add up to 1900 meters, which may be a bit long for some people (especially for the first attempt). One way to shorten them is to do them as 500-300-500-. Or you can try sets of 500--500--, where “--“ means two 100m floats…or 200m. Recover with an easy 400m jog between sets.

- Pre’s in-and-out 200s. This is Prefontaine’s famous 30-40 workout, but don’t try to mimic his speed. Run the fast 200s at somewhere between 1500m and 3000m race pace (probably closer to 1500m pace, once you get used to it), and the slower ones about 33 percent slower. And don’t try to challenge Pre’s and Rupp’s distance record. Two to three miles of this is a very good workout and quite enough!

- Aussie quarters. This is De Castella’s workout. In my group, we use this a lot. Start by doing the fast 400s at 5km pace, and the 200m floats at marathon pace, and try to hold it for 3 miles (or 4800m, on a track). If you get the pace wrong and tire, break it into sets, with a 400m recovery between sections. Once you learn the protocol, your metric for evaluating how well you do on this workout is total time for 3 miles/4800m. With practice, it’s possible to do the fast 400s at 3K pace, but the recoveries should remain at no faster than marathon effort, or you’ll turn the workout into a race.

- 700s. Most people never run 700m repeats, which is part of the fun of this workout. The idea is to run 1.75 laps fast, then complete the second lap with a float (probably a bit slower than you’d do for the 300-300-300-300- workout). Then jump right into another 700. Run the 700s somewhere between 10km and 15km pace. Take set breaks as needed. This is a good workout for marathoners, who can build up to as much as 10 percent of their weekly volume. I once coached a 2:46 female marathoner who could hold this workout for 8 miles, without a break.

- Long alternations. 600/400, 800/800, etc. These can be run either continuously or in sets, with a 3-to-5-minute jog between sets. The first part of each pair is the fast one. Do it fast, but not super-fast. As with the 700s, 10km to 15km pace is probably about right. The floats (the distances after the ‘/’) are at marathon pace. Thus, 600/400 alternations involve switching between 600s and 400s. Marathoners and half-marathoners will want to run the faster parts at fairly conservative paces, with the total volume of the alternations (counting the marathon-paced segments) adding up to perhaps 10 percent of their weekly volume, nonstop. Shorter-distance runners will want to run the fast sections at 10km pace or perhaps a touch faster, breaking up the session into 2000m or 3000m segments, with rest breaks between. These should build to either 6400m or 10 percent of total weekly volume, whichever is larger.

NB: Lactate-shuttle workouts aren’t just for runners; the same physiology applies to endurance athletes in other sports. Focus on ‘yo-yo’-ing your lactate levels by alternating between faster-than-threshold and slower-than-threshold (while still maintaining a brisk pace). If you’re a cyclist, use a power meter and start with something simple, like sets of 90sec/50 sec alternations (roughly equivalent to Aussies). You can then get more elaborate as you get a feel for the paces and rhythms that work for you.

CASE STUDY: Lindsey Scherf

Lindsey Scherf is an American road racer. She holds the second-fastest 25km time in US history, placed 2nd in the 2016 USA Track & Field road racing series, and holds the indoor world record for the marathon, plus a number of other honours, including one-time American junior track records at 5,000m and 10,000m.

One of her favourite workouts is what she calls “10km-style variations,” which are lactate-shuttle workouts such as sets of 4 x 2 minutes, with 30 seconds between speed bouts and three minutes between sets. Another favourite starts with 4 x 500m, with a 100m-float between each 500m and a 400m jog after the set. She then moves to 4 x 300m - again on a 100m float and a 400m recovery, before doing a final set of 4 x 200m. With each set, the pace speeds up. “It is basically done at 5km pace, down to close to 800m pace,” she says.

According to Lindsey, the primary advantage of such workout sis that they let her get in hard workouts at substantially faster than race pace, without breaking down her body. The rests keep her from beating herself up too badly, but are short enough that her heart rate doesn’t come down all that low. “I’m getting a high overall heart rate,” she says. “I’m able to combine a VO2max heart-rate session with velocities unmatched in a traditional mile-repeat or 800m-repeat session. I don’t know if this is for everyone, but for me it hits a sweet spot.” And, she notes, “It’s a nice format because it can be done on the track, off the track, on the hills, or on the flat. You can do it time-based [or] effort [based].”

- References

- 1) Peter Thompson, New Interval Training: ‘The most significant advance in running training since the original interval training,’ www.newintervaltraining.com (undated)

- 2) PNAS February 2, 1999. 96 (3) 1129-1134; doi.org/10.1073/pnas.96.3.1129

- 3) Physiology, 30 November 2009 doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2009.178350

- 4) Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. Volume 120, Issue 1, May 1998, Pages 89-107. doi.org/10.1016/S0305-0491(98)00025-X

- 5) Neuroscience, Vol. 145(1), 2 March 2007, Pages 11-19

- 6) Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1986 Jun;18(3):360-8

- [7] Thorax 38:50-54 (1983)

The key to both of these are the brisk recoveries. A lot of coaches - myself included - like to call them floats. “Float, don’t jog,” is what I tell people. Thompson prefers the term “roll-ons” because you roll on from the faster part of the cycle into a still-brisk pace. Whichever term you prefer, the idea is that these recoveries are brisk. If you get them right, you’ll spend the first two-thirds of the float watching the start of the next speed bout 100m closer, wondering how you’ll ever be recovered enough to speed up again. Then, in the last few meters, you’ll discover you can actually do it.

Magic in the float

The new science by Brooks, Thompson, and others has produced a theory for why it works, and with it, insight into how to fine-tune Prefontaine and De Castella’s decades-old methods. Brooks’ studies suggest that the ‘magic’ in this type of training comes from the float, not from the higher-intensity work that preceded it. The primary function of the fast parts of the workout, it turns out, is simply to work you hard enough to cause your blood lactate to rise. Once that has happened, you transition to the float. This trains your body to clear lactate efficiently, while still running at a brisk speed - though not so brisk that you are still accumulating lactate. In other words, what you are training is the lactate shuttle.There is no single best way to do this. Rather, it varies with your goals, personality, and, ultimately, inventiveness. Prefontaine did it by running really fast 200s—fast enough to quickly build up a surplus of lactate then following them with recoveries that were a full 33% slower. It’s the equivalent to someone with a 5:50 mile PB doing the fast 200s in 45 seconds and the floats in 60 seconds. It looks superhuman only because Prefontaine was fast, and because he could hold it for such a long time. De Castella ran a higher fraction of his workout at the fast pace, but kept the pace slower. That allowed him to recover from 400m speed bouts in only 200m, rather than having to run a full 400 before he was ready to speed up again.

Alberto Salazar once told me that back in his prime, he used to do something similar, albeit with longer repeats. His workout alternated miles at 10 seconds faster than marathon pace (probably quite close to his threshold pace) with miles at about 20 seconds per mile slower than marathon pace. His goal was largely psychological; a long series of such repeats, he said, made marathon pace feel comparatively easy. But years before Brooks discovered the lactate shuttle, he too had also found a pace-varying speed workout that, although quite different from Prefontaine’s and De Castella’s, was probably working the same physiological processes.

Pacing the float

Scientifically, the goal is to run the float briskly, but not too briskly. It has to be slower than threshold pace, or you’ll continue to accumulate lactate, rather than training your body to clear it. But it shouldn’t be too slow, or it won’t train your lactate shuttle to use that lactate efficiently when you’re working hard. Finding the right pace is fairly subjective. The key thing is not to slow to a walk, or even a jog, the moment you hit the end of the fast repeats. If you’re schooled in conventional intervals, this will be hard, because in them, the goal is to recover as quickly as possible. Here, the goal is to keep moving. I tell people to ‘trust the recovery to come to them before the next repeat begins’. If it doesn’t, it’s probably the repeat that you did too fast, not the float.If you’re really determined to check your watch, another metric is that as you start this type of training, your floats will be fairly slow. As you both learn the method and get fitter, they will speed up. When you are truly fit, your floats may be as little as 4 seconds per 100m slower than your speed bouts - little enough that people watching you may not be able to detect them without a stopwatch.

Practical advice for training sessions

Once you understand the science, there are a nearly unlimited number of ways to put it into practice. Here are a few:- Sets of 300-300-300-300-s. The hyphen here is a 100m float, so this workout is a set of four fast 300s, each followed by a 100m float. (Note: the last 300 is also followed by a float; the floats are where the lactate-shuttle training occurs, so all such workouts end with a float.) Run the 300s at somewhere between 5km to 3km pace. Between sets, do an easy 400m recovery. The total number of sets should be about the same as you’d do for traditional 1200m repeats (possibly one less, since the 100m floats can add up). You can also do this as sets of 300-300-300 (which might be easier first time).

- Patched-together miles. These are like the 300s, but with longer segments. For example, you could do sets of 600-400-600-. Pace the fast parts no faster than your 5km pace. Note that counting the floats, these sets actually add up to 1900 meters, which may be a bit long for some people (especially for the first attempt). One way to shorten them is to do them as 500-300-500-. Or you can try sets of 500--500--, where “--“ means two 100m floats…or 200m. Recover with an easy 400m jog between sets.

- Pre’s in-and-out 200s. This is Prefontaine’s famous 30-40 workout, but don’t try to mimic his speed. Run the fast 200s at somewhere between 1500m and 3000m race pace (probably closer to 1500m pace, once you get used to it), and the slower ones about 33 percent slower. And don’t try to challenge Pre’s and Rupp’s distance record. Two to three miles of this is a very good workout and quite enough!

- Aussie quarters. This is De Castella’s workout. In my group, we use this a lot. Start by doing the fast 400s at 5km pace, and the 200m floats at marathon pace, and try to hold it for 3 miles (or 4800m, on a track). If you get the pace wrong and tire, break it into sets, with a 400m recovery between sections. Once you learn the protocol, your metric for evaluating how well you do on this workout is total time for 3 miles/4800m. With practice, it’s possible to do the fast 400s at 3K pace, but the recoveries should remain at no faster than marathon effort, or you’ll turn the workout into a race.

- 700s. Most people never run 700m repeats, which is part of the fun of this workout. The idea is to run 1.75 laps fast, then complete the second lap with a float (probably a bit slower than you’d do for the 300-300-300-300- workout). Then jump right into another 700. Run the 700s somewhere between 10km and 15km pace. Take set breaks as needed. This is a good workout for marathoners, who can build up to as much as 10 percent of their weekly volume. I once coached a 2:46 female marathoner who could hold this workout for 8 miles, without a break.

- Long alternations. 600/400, 800/800, etc. These can be run either continuously or in sets, with a 3-to-5-minute jog between sets. The first part of each pair is the fast one. Do it fast, but not super-fast. As with the 700s, 10km to 15km pace is probably about right. The floats (the distances after the ‘/’) are at marathon pace. Thus, 600/400 alternations involve switching between 600s and 400s. Marathoners and half-marathoners will want to run the faster parts at fairly conservative paces, with the total volume of the alternations (counting the marathon-paced segments) adding up to perhaps 10 percent of their weekly volume, nonstop. Shorter-distance runners will want to run the fast sections at 10km pace or perhaps a touch faster, breaking up the session into 2000m or 3000m segments, with rest breaks between. These should build to either 6400m or 10 percent of total weekly volume, whichever is larger.

CASE STUDY: Lindsey Scherf

Lindsey Scherf is an American road racer. She holds the second-fastest 25km time in US history, placed 2nd in the 2016 USA Track & Field road racing series, and holds the indoor world record for the marathon, plus a number of other honours, including one-time American junior track records at 5,000m and 10,000m.

One of her favourite workouts is what she calls “10km-style variations,” which are lactate-shuttle workouts such as sets of 4 x 2 minutes, with 30 seconds between speed bouts and three minutes between sets. Another favourite starts with 4 x 500m, with a 100m-float between each 500m and a 400m jog after the set. She then moves to 4 x 300m - again on a 100m float and a 400m recovery, before doing a final set of 4 x 200m. With each set, the pace speeds up. “It is basically done at 5km pace, down to close to 800m pace,” she says.

According to Lindsey, the primary advantage of such workout sis that they let her get in hard workouts at substantially faster than race pace, without breaking down her body. The rests keep her from beating herself up too badly, but are short enough that her heart rate doesn’t come down all that low. “I’m getting a high overall heart rate,” she says. “I’m able to combine a VO2max heart-rate session with velocities unmatched in a traditional mile-repeat or 800m-repeat session. I don’t know if this is for everyone, but for me it hits a sweet spot.” And, she notes, “It’s a nice format because it can be done on the track, off the track, on the hills, or on the flat. You can do it time-based [or] effort [based].”

- References

- 1) Peter Thompson, New Interval Training: ‘The most significant advance in running training since the original interval training,’ www.newintervaltraining.com (undated)

- 2) PNAS February 2, 1999. 96 (3) 1129-1134; doi.org/10.1073/pnas.96.3.1129

- 3) Physiology, 30 November 2009 doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2009.178350

- 4) Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. Volume 120, Issue 1, May 1998, Pages 89-107. doi.org/10.1016/S0305-0491(98)00025-X

- 5) Neuroscience, Vol. 145(1), 2 March 2007, Pages 11-19

- 6) Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1986 Jun;18(3):360-8

- [7] Thorax 38:50-54 (1983)

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.