You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Strength: training to failure – yes or no?

How hard should you push yourself when strength training? As Andrew Sheaff explains, new research suggests more might not be better…

There are many points of contention when it comes to the optimal way to develop muscle strength and growth (hypertrophy). From free weights versus machines, to single-joint versus multi-joint lifts, to varying repetitions speeds and ranges, the debate rages. However, no topic is more controversial than whether individuals should or should not train to failure (the fatigue level at which it is physically impossible to perform another rep) in order to optimize progress.

Prior research

Training to failure is a topic that Sports Performance Bulletin has addressed before. A recent article examined a study that looked into this very question. The researchers in this study had subjects perform one of three different training protocols(1). The subjects either performed three sets to failure, four sets not to failure (with the extra set to match the total reps volume of the failure group), or three sets not to failure. After five and ten weeks, there were no differences between groups. They all were equally effective. In fact, a measure of power output was improved in the groups that did NOT train to failure, a finding absent in the group training to failure. Avoiding failure appeared therefore to be advantageous.

A second SPB article looked into this topic further. The researchers had the subjects perform one of two types of bench pressing sessions(2). In one session, the subjects performed five sets to failure. In the other session, the subjects performed four sets with three repetitions in reserve – ie they stopped 3 reps short of failure. On the final set, they performed the set to failure. The results indicated that keeping reps in reserve allowed for the subjects to perform more total work across the five sets. Staying away from failure allowed for more quality repetitions, exactly what an athlete wants!

Controversy

While these studies provide convincing evidence that training to failure isn’t required for optimal progress, evidence does exist to refute these claims. There appear to be specific circumstances where training to failure is potentially superior to avoiding failure. A recent study had subjects perform one of four training protocols over the course of the 8-week study(3). The participants performed sets with light loads or heavy loads, and they performed sets to failure or not to failure.

The results showed that hypertrophy increased when using heavy loads regardless of training to failure, and when using light loads and training to failure. However, no changes were found when using light loads and avoiding failure. The conclusion is that if training with light loads, exercising to failure will likely be required to maximize improvement.

Moreover, there is evidence that maximal muscle activation is only achieved by training to failure in individuals with a significant strength training background(4). This is true regardless of whether the load is light or heavy. This effect is not seen in untrained individuals. As maximal muscle activation is thought to be necessary for maximal adaptation, occasionally training to failure may therefore be necessary for advanced trainees.

Definitive answers

With these somewhat conflicting and contradictory findings, it’s natural to ask which approach is best. A group of researchers recently sought to answer this question by performing a meta-analysis that examined all of the previous studies examining training to failure and pooling the data(5). They also looked at studies that investigated the impact of velocity loss thresholds. This involves tracking the speed of the bar/dumbbell etc throughout the course of a set. As fatigue accumulates, the bar speed will slow. The more it slows, the closer one is to failure. Studies often implement various ‘velocity loss thresholds’ to determine when the set is complete. For instance, it the set stops when velocity drops by 40% versus 20%, that would indicate greater muscle fatigue and closer proximity to failure.

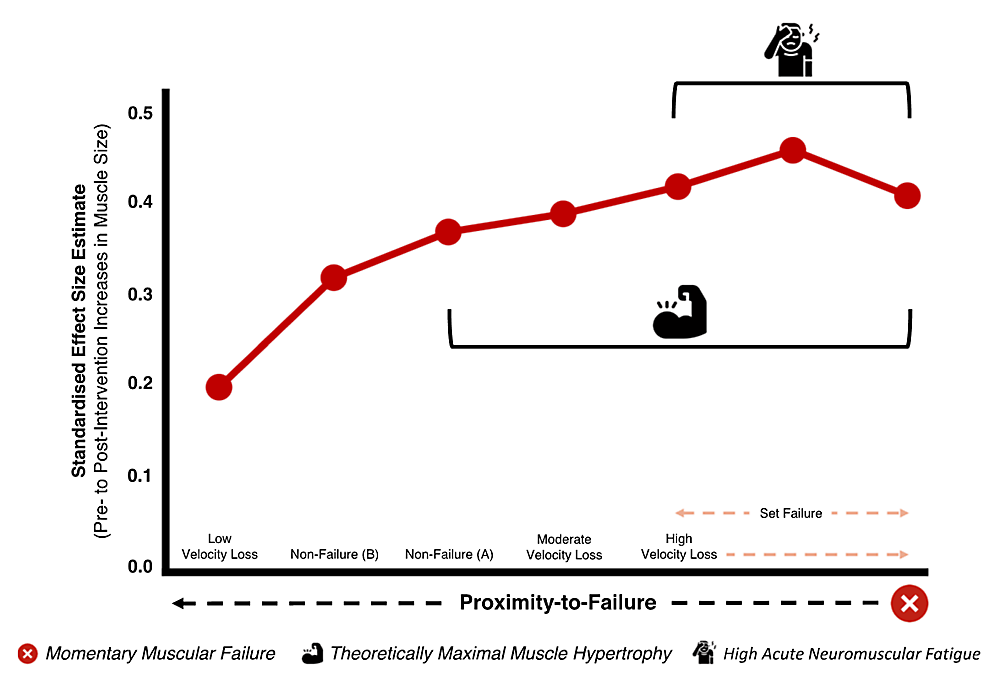

A total of 15 studies were included in the meta-analysis. After running the numbers, the researchers found there was only a trivial benefit of training to failure as compared to not training to failure. They concluded that there is no evidence to support the superiority of training to failure. They also concluded using higher velocity loss thresholds, indicating greater levels of fatigue, do not always lead to larger increases in muscle hypertrophy (see figure 1).

This led the researchers to conclude the relationship between proximity to failure and improvements in muscle mass may be non-linear. While initial increases in proximity to failure lead to large increases in hypertrophy, getting closer and closer to failure may not yield the same benefits. In other words, one needs to train hard enough and get close enough to failure to stimulate progress. However, training harder than that does not necessarily lead to improved hypertrophy gains.

Figure 1: Strength effects as failure point is approached

Vertical axis shows size of muscle growth effect. Horizontal axis runs from light loading on the left to muscle failure on the right. Muscle growth effects were greatest when training with moderate to high velocity loss. However, training to complete failure was less effective and produced much higher fatigue levels than training with high velocity loss but stopping short of failure.

What’s the approach for you?

For most athletes and most individuals, it appears that training to failure is not a necessary strategy to optimize gains in muscle strength and hypertrophy. This is likely to be even truer for those individuals who must complete several different types of training. For team sport or endurance athletes, strength training is simply one aspect of the training process that must be balanced against the others.

Bear in mind that training to failure greatly increases the fatigue that is generated. Consequently, this fatigue can negatively impact other components of your training plan. While this could potentially be worth it if that extra fatigue generates further improvements, this doesn’t appear to be true. Time and energy would be better spent strength training ‘hard enough’, saving precious resources for other important training sessions.

However, there may be specific situations where training to failure is warranted and appropriate. If using lighter loads due injury, the lack of availability of equipment, or some other reason, taking your sets much closer to failure is warranted because muscle growth will be optimized by doing so. Likewise, the further you are along your strength journey, and the stronger you are, the more you should consider training to failure, at least on the odd occasion. It might be required for you to continue to improve your strength and muscle growth.

References

1. Eur J Transl Myol. 2017 Jun 27;27(2):6339. doi: 10.4081/ejtm.2017.6339. eCollection 2017 Jun 24.

2. Strength Cond Res. 2022 Jan 1;36(1):1-9. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000004158.

3. Strength Cond Res. 2022 Feb 1;36(2):346-351. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000003454.

4. Front Physiol. 2016 Jan 29;7:10. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00010. eCollection 2016.

5. Sports Med. 2023 Mar;53(3):649-665. doi: 10.1007/s40279-022-01784-y. Epub 2022 Nov 5

Related Files

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.