You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Hill and sprint cycling: stand and deliver!

What are the best out of the saddle techniques for cyclists? SPB looks at the recent research

As any cyclist knows, when the road points upwards, the gradient gets steep and you run out of gears, there comes a point at which the seated position is no longer tenable. An accumulation of lactate in the bloodstream and acidity in the working muscles leads to burning fatigue – at which point cyclists often transition from a seated to a non-seated position by getting out of the saddle and standing on the pedals. Field testing (ie riding in real world conditions) research by Hansen at al has shown that competitive cyclists can increase their time to exhaustion during uphill cycling by using the non-seated posture when the required power output to maintain a desired velocity is at or above 420 watts(1). The same researchers also showed that when the cyclists adopted a standing position, their preferred cadence decreased from 92rpm when seated to 74rpm standing.Force generation in a standing position

Why does getting out of the saddle help cyclists overcome steep gradients when fatigue accumulates? The simple explanation for this observation is that getting out of the saddle allows more extended hip and knee angles, which in turn produces an effective use of body mass to generate positive power at the crank during the downstroke(2). The preference for a lower cadence when standing also suggests that cyclists favor generating extra power at the crank by increasing crank torque (turning force) and reducing crank angular velocity (pedal rotation speed).However, while it is known that the non-seated posture is more effective than the seated posture for maximal power production, it’s also known that cyclists often transition off the saddle well before their limit of power production is reached(3). For example, in a study using an incremental testing protocol in a laboratory, researchers found that non-cyclists spontaneously transitioned to a standing position at around 570 watts when pedaling at a cadence of 90rpm. While this seems reasonable, this was well below the 6-second maximal power production of around 800 watts(4,5).

The downside of being upstanding

Why do cyclists tend to get out of the saddle well before the limit of power production is reached? One explanation is that by doing so, there’s less chance of extreme fatigue setting in. Avoiding extreme fatigue will therefore help prolong performance. This is borne out by the research on uphill cycling outlined above(1). If that’s the case and maximal force production is significantly greater, why shouldn’t cyclists spend as much time out of the saddle as possible when the road points upwards and the going gets tough?The reason is that research has shown that cycling in a standing position reduces cycling economy compared with seated cycling(6). In other words for a given speed/power output, more energy is expended per mile when standing compared to when sitting. However, as the cycling intensity rises, the drop in cycling economy produced by standing diminishes. This means that at very high intensities, while a cyclist may become slightly less efficient, the efficiency drop is minimal and easily compensated for by a gain in maximal power output and drop in lactate production (ie less fatigue). But as we’ll see shortly, the technical features of the standing position (ie the cyclist’s and bike’s alignment and movements during non-seated cycling) may also be a significant factor in how much efficiency loss occurs during out of the saddle cycling(7).

Out of the saddle technique

As we’ve ascertained, the point of getting out of the saddle is to help muscles to generate more crank torque without needing to work absolutely flat out, thereby avoiding debilitating fatigue. But where seated cycling remains possible without excessive fatigue, it is preferred due to its high efficiency. The next question is whether there exists a preferred technique for out of the saddle riding?As seasoned cyclists will know, climbing while out of the saddle involves some degree of ‘leaning the bike’ alternately from left to right to let and so on. However, the rider him/herself does not lean anywhere near as much; the idea is that when the bike leans to one side, the rider’s center of mass can switch to the opposite side, thereby helping to drive the crank downwards more forcefully (see figure 1).

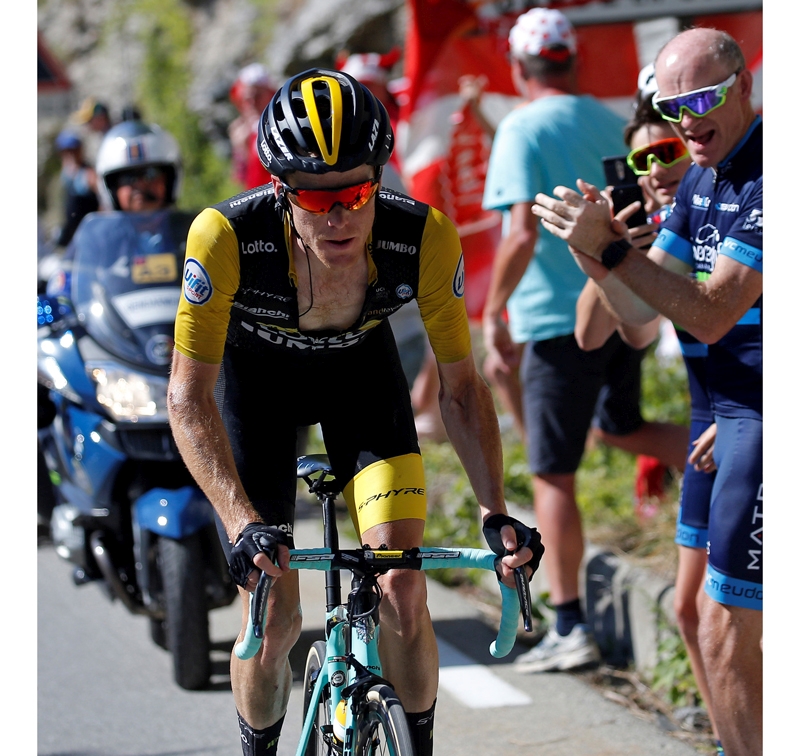

Figure 1: Bike lean and center of mass

The bike leans slightly to the right (in this image), allowing the rider to shift his center of mass over the left pedal and generate more downwards force.

That this is a real phenomenon has been verified by research. A study last year which looked at how riders used their body mass to amplify crank power during non-seated ergometer cycling(8). In this study, the bike position was fixed but the lab setting nevertheless allowed the research to assess center of body mass changes and how it affected power outputs. The changes/movements of center of mass and the corresponding joint power of 15 participants riding in a non-seated posture was assessed at three individualized power outputs (10%, 30%, and 50% of peak maximal power) and two different cadences (70 and 120 rpm).

What they found was that the peak-to-peak amplitude of center of mass displacement increased significantly with increasing power output and with decreasing cadence. The greatest amplitude of center of mass displacement was around 6cms; at the same combination of high-power output and low cadence, we found that the peak rate of CoM energy loss (3.87 watts per kilo, equal to 18% of the peak crank power. In short, it appears that for a given power output, changes in center of mass can contribute to peak instantaneous power output at the crank, thus reducing the required muscular contribution – ie helping to reduce fatigue.

How much bike lean?

The rationale for some bike lean when cycling out of the seems solid; shifting the rider’s center of mass to generate more torque on the crank downstroke helps lessen the onset of fatigue compared to either seated cycling or no ‘center of mass displacement’ while out of the saddle cycling. The next question is whether there’s an optimal amount of bike lean for force generation?To date, there’s been no evidence to help answer this question, but a brand new study published in the Journal of Biomechanics titled “The influence of bicycle lean on maximal power output during sprint cycling” has attempted to answer this question(9). In particular, the researchers sought to find out whether (putting aside center of mass changes aside) leaning the bicycle while out of the saddle or conversely, attempting to minimize lean, affects maximal power output during sprint cycling.

To do this, the scientists modified a cycling ergometer so that it could lean from side to side but could also be locked to prevent lean. This modified ergometer set up made it possible to compare maximal 1-second crank power during non-seated, sprint cycling under three different conditions. These were as follows:

- Locked (no leaning permitted.

- Unlocked with ad libitum lean (the cyclists leaned the bike as much as they felt they needed to in order to maximize their sprinting performance).

- Unlocked while trying to minimize bike lean (the cyclists tried to maintain an upright position) even though the bike could lean.

The researchers concluded therefore that when leaning a bike during sprinting, riders should not try and minimize lean in an effort to try and adopt a more streamlined position because this results in lost power. Instead they should lean the bike as much as they feel the need to. Why was the locked position as efficient as the freely leaning position? The likely answer that with a static immovable frame, the riders were able to deploy more upper body muscle power to stabilize the torso during center of mass shifting, which enabled more directed force development at the crank. This was no doubt aided by the static position of the frame which was not moving underneath the riders during sprinting.

Implications for cyclists

How can we sum up the findings on non-seated cycling and what are the implications for cyclists? Here are some key points:- Cyclists can be confident that there’s a good rationale for getting out of the saddle when the gradients become steep (or during a sprint), which requires a temporary high power output. However, since out of the saddle cycling is less efficient, cyclists should always use a lower gear where possible before standing on the pedals. To minimize standing, some sessions of pushing a big gear while seated can help improve power delivery in the saddle, thereby obviating the need to stand.

- When getting out of the saddle, cadence should be dropped to around 75rpm to help mitigate efficiency losses.

- Leaning the bike slightly so that the center of mass is transferred to the downstroke crank not only feels natural but will actually improve power delivery and – importantly – increase efficiency.

- For short sprints or maximal efforts, allow the bike to lean as much as feels natural. Don’t be tempted to minimize lean in an effort to stay more streamlined – you will end up losing power!

- J Sports Sci. 2008;26(9):977–84

- J Biomech. 1995;28(4):365–75

- Sci Sports. 2007;22:190–5

- Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1987;56:650–6

- J Biomech. 2015;48(12):2998–3003

- Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2016 Oct;11(7):907-912

- Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002 Oct;34(10):1645-52

- Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2020 Dec;52(12):2599-2607

- J Biomech. 2021 Jun 29;125:110595. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2021.110595. Online ahead of print

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.