You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Interval training for team sport: straight up or round the houses?

In team sports such as soccer and rugby, players need to be fast, agile and able to execute rapid changes of direction. So does straight-line interval training cut the mustard or is there a better way? SPB looks at new research

In recent years, a growing body of evidence has accumulated showing that performing regular bouts of intensity interval training is an extremely effective training tool for athletes seeking to maximize performance for a relatively low training workload(1). Put simply, short sessions of intensity intervals are a great way of producing gains in aerobic power, enabling an athlete to sustain a higher intensity/pace/workload for longer before fatigue sets in.

What intensity?

What are the characteristics of interval sessions that are likely to produce good gains in fitness? In particular, how intense should they be? When we look at the findings from existing research, we see that best training effects in terms of improving fitness (ie increased stroke volume and oxygen delivery around the body), is achieved at training intensities between 85%–95% of maximum heart rate(2,3), or possibly even higher(4). In other words, what seems to work best are high-intensity interval sessions that manage to raise heart rate to around 90% or even 95% of maximum for a reasonable period to time.

To understand why high-intensity interval training (HIIT) is so effective, consider that the intense nature of the intervals in a session means that an athlete performing them will experience a more rapid rise and greater increase in heart rate during each interval, which will mean a greater time proportion of each interval will be spent above 90% maximum heart rate. Of course, in very intense intervals, each interval duration will be likely be shorter than a lower-intensity interval session, so the total time accumulated above 90% maximum heart rate might not be that much greater. However, as a proportion of the total work performed, HIIT provides an excellent way of ensuring an effective training stimulus.

HIIT and team sports

Team sports such as soccer, rugby, hockey, basketball are typically characterised by high intensity bursts of activity, interspersed by lower intensity activity and stoppages in play of various lengths(5). Moreover, robust research shows that the ability to perform at these high intensities, recover adequately between intense bursts and to repeat these maximal intensity actions for the duration of a match is a crucial quality that team players need to develop in preparation for competition(6).

A good example of the importance of high-intensity performance comes from data gathered from soccer players competing in the UK’s Premier League(7). This data reveals the following:

· A player makes on average over 1,000 changes in playing activity during a game, which equates to a change in movement every four to six seconds.

· Although 85 to 90% of the 10-12km distance covered in a match is at low- or sub-maximal intensities the distance run at a high-intensity is significant – typically around 1.2-25kms(8,9).

· The distance covered performing high-intensity running is the most valid and reliable indicator of a player’s performance capability, even though it constitutes a much smaller proportion of a player’s activity profile.

· What really marks out elite soccer players is that they run much further at a high-intensity during a game than moderate-standard players.

· It is during high-intensity periods of play that the outcome of a game is often decided.

The application of HIIT for female players

In theory, using HIIT to improve the performance of team sport players seems ideal, but much of the research to date on HIIT and sport performance has been carried out in endurance athletes such as cyclists and runners. Also, most of the studies on HIIT and team sport performance to date have tended to use male players. However, there are some studies that have focused on HIIT and the benefits for female team sport athletes. These include studies that found(10-12):

· Meaningful improvements in aerobic and anaerobic capacity in amateur female soccer players.

· Positive effects on VO2max (gains of 3.4–4.7%) in female college soccer players.

· Moderate improvements in regional-level soccer players in the 20-metre and repeated sprint test after six weeks of training.

Overall however, the effects of HIIT on physical performance in elite female team sport players remain relatively unproven due to the scarcity of research attention.

Straight line vs. change of direction

Here’s a question: if team sport players need to perform repeated sprints while also performed numerous changes of direction, shouldn’t all HIIT training also be performed using changes of direction (COD) during the intervals? After all, the ‘specificity of training’ principle states that for maximum training adaptations, athletes should train in a way that most closely replicates the physical demands of their sport. It turns out that many team sport coaches (for example in soccer) do prefer HIIT training with changes of direction (HIIT-COD), which is more specific, in terms of movement patterns, to the female soccer match.

This question has been partially investigated in male soccer players, where researchers found that a combination of HIIT and COD training lead to improved aerobic and anaerobic capacity in male soccer players(13). Perhaps more relevant to answering the question was a 2018 study on professional futsal players, which concluded that HIIT with three directional changes per running bout achieved superior improvements in aerobic capacity, running economy, and repeated sprint ability compared to one directional change in female futsal players(14). Despite these findings, there’s not been a back-to-back test comparing the training benefits of straight-line vs. change of direction intervals, and certainly not in soccer players.

New research

Fortunately, a study on this very topic has just been published by a team of Serbian scientists(15). Appearing in the journal ‘Biology of Sport’, this study compared the performance effects of HIIT performed in a straight line with the same intervals performed using changes of direction (ie more specific to the demands of team sports) in elite female soccer players. The scientists’ hypothesis was that while either type of HIIT would benefit straight line sprinting ability, the change of direction HIIT would produce superior results when the players were sprinting in a non-linear fashion.

What they did

Thirty elite female soccer players participated in this 6-week intervention study. To qualify, players had to be over the age of 15 (the average age was 19 years), competing at the highest level of soccer competition, carrying out at least five training sessions per week and free of injury – either at the time of recruitment or for the prior three months (12 months in the case of anterior cruciate ligament surgery). The players were then randomly allocated to one of two intervention groups:

· HIIT group using linear running intervals (HIITLIN) – in this group, participants performed two sessions per week of linear running intervals using durations of 15, 20 or 25 seconds, by keeping a constant pace during the entire distance in a straight line.

· HIIT group using change of direction intervals (HIITCOD group) - in this group, participants performed two sessions per week of change of direction running intervals involving a 180-degree turn during each running interval. As above, each running interval was for a duration of 15, 20 or 25 seconds. However, due to the extra energy required to execute 180-degree turns, the individual interval distance for the HIITCOD group was reduced by 7% to compensate. NB: this correction is based on the ‘Laursen & Buchheit’ recommendation that excess energy consumption should be compensated by reducing the distance by 2–3% for each COD compared to a straight line(16).

Each session during the entire training program involved work intervals of running effort adjusted for each participant’s individual level of fitness (derived from the 30–15 Intermittent Fitness Test(16)) interspersed by an equivalent amount of passive recovery. The training load was gradually increased from week 1 to week 6; the actual week-by-week training plans for both intervention groups can be seen here. All of the HIIT sessions during the intervention period were performed outdoors on the field with natural grass (ie to replicate actual playing conditions). Participants performed standardized warm-ups consisting of moderate-intensity jogging (5 minutes), static and dynamic stretching (5 minutes), passing and receiving drills (5 minutes) and acceleration running (2 minutes) prior to each HIIT session.

Testing for performance

At the start of the 6-week study and then again at the end of the six weeks, all the participants performed a series of tests. These were as follows:

· Speed (running 0–30 m) - This study used 10 m, 20 m, and 30 m linear sprinting tests. Participants were instructed to run as quickly as possible over the distance from a standing start.

· Repeated sprint ability (RSA) - The repeated sprint ability (RSA) test consisted of six 40m sprints separated by 20 seconds of passive recovery.

· 30–15 Intermittent Fitness Test - The 30–15 IFT test was performed by placing cones 40 m apart and performing shuttle runs at increasing frequency and speed dictated by an audible bleep.

· 9-6-3-6-9 sprint (with 180° turns) - The players started after the signal and ran 9m. Touching the line with one foot, they made a turn of 180° to the left or the right. The players then ran 3m to the next line, made another 180° turn and ran 6m forward. Then they made another 180° turn and ran 3m forward, before making the last turn and the final 9 m run to the finish line.

· Zigzag test - The course consisted of four 5m sections (20 m in total) and required participants to slow down and accelerate around each cone as quickly as possible, from separated starting and finishing points.

· Pro-agility test – this assessed the ability to change direction laterally to the right and left.

· Vertical jumps (CMJ, CMJA, SJ) - Three types of vertical jumps were used to evaluate jump height (cm) – countermovement jump (CMJ), CMJ with arm swing (CMJA) and squat jump (SJ).

The results from pre- and post-intervention testing were then analyzed with the results of the two groups compared to see if the change of direction protocol produced superior results to the linear protocol.

What they found

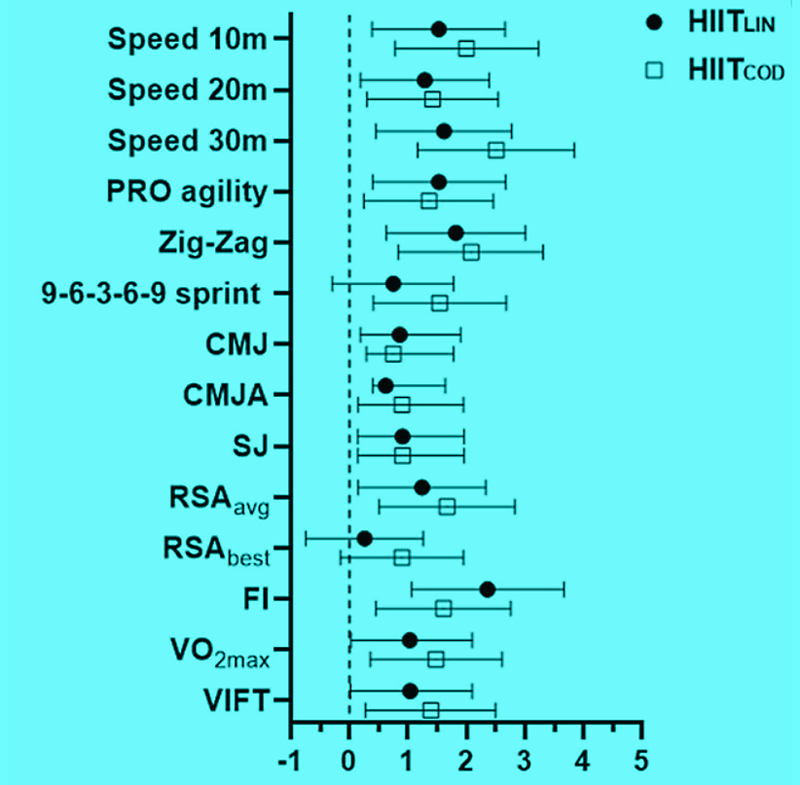

When the data was number crunched, the findings were not as expected. Both interventions, HIITLIN and HIITCOD, significantly improved sprint speeds over 10m, 20m and 30m, Pro-agility (lateral movement ability), the Zigzag test, repeated sprint ability, FI, aerobic capacity (VO2max), and the shuttle run performance test, while moderate improvements were observed in CMJ, CMJA and SJ (see figure 1). However, the really significant finding was that the change of direction intervals did NOT achieve superior improvements in any of the aforementioned measurements compared to the much simpler linear intervals. Although there were slight differences in the outcomes, these were non-significant and so small that they could have occurred by chance. NB: for a full breakdown of the results, see table 2 of the study.

Figure 1: Comparison of findings from linear vs. COD high-intensity intervals

Practical implications for team sport players

The conclusion from these findings are very straightforward – basically that there are no significant benefits to be had by performing high-intensity interval sessions using changes of direction. This seems to be the case even though the testing procedures included lots tasks involving changes of direction of the sort that players need to perform on the pitch.

Looking at figure 1, we can see that in many of the measures, the COD intervals showed a slightly higher effect size, but this additional effect was too small to be significant. It’s possible however that using a larger study with more participants, we might be able to detect some significant benefits by using COD intervals. But for now at least, we much conclude linear and COD intervals are equally effective in performance terms.

Something else to consider is injury risk. Sudden changes of direction at speed add extra loading to joints, tendons and ligaments, which means the COD interval sessions will inevitably impose more demands on the musculoskeletal system than linear sessions. The fact that linear intervals can yield the same performance benefits as COD intervals is therefore good news for team sport players because with less loading, there is a reduced risk of injury. In short, coaches and players that use HIIT sessions to improve performance should always go for straightforward (no pun intended!) linear sessions as they deliver the performance goods, are simpler to perform and are less onerous on joints, ligaments and tendons!

References

1. Sports. 2015 Oct;45(10):1469-81

2. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2013, 27, 1974–1980

3. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2013, 23, 74–83

4. Sports Med. 1986, 3, 346–356

5. Sports Med. 2017;47:2533–2551

6. PLoS One. 2017 Feb 15;12(2):e0171462

7. ’Managing high-speed running load in professional soccer players’ SPSR 2019 March (53) volume 1

8. Hum Mov Sci. 2013; 32(6):1430–42

9. J Sports Sci. 2008 Jan 15;26(2):113-2

10. Sports. 2017; 5(3):57

11. Int J Exerc Sci. 2012; 5(3):6

12. J Sports Sci. 2016; 34(19):1808–15

13. J Strength Cond Res. 2015; 29(10):2731–7

14. Hum Mov Spec Issues. 2018; 2018(5):40–51

15. Biol Sport. 2024 Oct;41(4):31-39. doi: 10.5114/biolsport.2024.134761

16. Laursen P, Buchheit M. Science and application of high-intensity interval training. Human kinetics; 2019

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.