You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Marathon Training: distance running at the North Pole

Runners competing in the North Pole Marathon

With temperatures ranging from -10 to -35°C, running the North Pole marathon is a huge challenge. Andy Lane and Tracey Devonport explain how to prepare for such events using data from a recent successful case study.

Completing a marathon was once considered an outstanding feat of endurance performance. However, with tens of thousands of runners – including many celebrities and first-time runners – annually completing big international marathons such as London and New York, a marathon is no longer held in such esteem.

When runners look for new challenges, therefore, some look for more extreme events. The North Pole marathon is such an example. The distance of 26.2 miles is the only similarity between the North Pole marathon and other marathons. Athletes have to endure running in temperatures from -10 to -35°C, sometimes running in snowshoes on uneven ground, comprised of ice and softer snow. This article considers how an athlete can prepare psychologically to ensure that coping resources are in place to meet the challenges presented.

The challenge

Kirsty Devonport is a 31-year-old female who has completed marathons recreationally for two years, her personal best time being 3 hours 33 minutes. To prepare herself for the North Pole marathon she came to us for physiological and psychological support.Some of the challenges she faced are common to people who seek to achieve demanding goals in different aspects of their life. Many people will identify with difficulties in finding time to train, due to a demanding vocation. However, the North Pole marathon also presents specific challenges, including locating and purchasing specialised kit, having confidence in the kit, training, and the ability to manage the harsh environmental conditions of the North Pole.

Kirsty explained that she found it difficult to develop confidence in her ability to manage challenges resulting from North Pole conditions because she lacked the necessary experience and was therefore unable to anticipate these conditions and challenges.

How support was provided

Working in conjunction with John Iga (University of Gloucestershire) we built a support package around two specialist-training sessions. The University of Gloucestershire has an environmental chamber suitable for the task. Over two consecutive weekends, Kirsty spent 100 to 120 minutes completing activities in an environmental chamber designed to recreate conditions of the North Pole.The temperature ranged between -20 to -25°C, and two large fans were utilised to expose her body to wind chill. In order to monitor her ability to maintain body temperature, we recorded her core body temperature, skin temperature and heart rate for the duration of testing. This physiological data was not only valuable in testing the efficacy of her kit, but also in monitoring her health and safety.

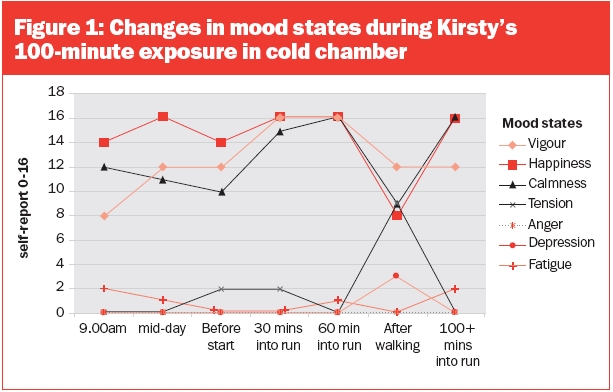

In order to monitor Kirsty’s emotional responses to cold conditions we asked her to complete a ‘mood measure’ twice on the morning of the training session and at various stages before, during and after the run (see below). Each time, Kirsty was asked to report on her feelings of vigour, fatigue, happiness, calmness, anger, depression and tension(1) at the moment of questionnaire completion.

Kirsty was also asked to complete a questionnaire that measured the extent to which she used 14 different coping strategies, including planning, positive thinking and using emotional support(2). She completed one questionnaire on the morning of testing to assess the coping strategies she had utilised generally over the past week. She completed the coping measure questionnaire again before entering the environmental chamber, and once more 90 minutes into testing, to identify the coping strategies utilised at that point. The intention was to gather physiological and psychological data to provide guidance on the ways in which Kirsty could maintain body temperature and manage any emotions and thoughts accompanying exposure to extreme cold.

Basing our advice on the experiences of those who have been exposed to extreme cold, we told Kirsty that she should initially exercise at a pace slower than she would normally run at in the early stages of the run, building up the pace to generate more heat as the duration of exposure to cold continued. As such, Kirsty began running at 11kmh, concluding the test with a pace of 13.5kmh. While these speeds might appear slow, times for the North Marathon are typically slower, with the personal best time for a woman being 5hrs 52 minutes 56 seconds (2006).

Over both weeks, Kirsty completed the following activities while in the chamber:

- A 30-minute run followed by a brief stop to complete a mood questionnaire (stop duration 3-4 minutes);

- A 30-minute run followed by completion of a mood questionnaire and removal and replacement of shoes (4-5 minutes);

- A 10-minute walk followed by completion of a mood questionnaire;

- A final 30-minute run followed by completion of mood and coping questionnaires.

Kirsty’s mood profile for the first run in the cold chamber (see figure 1) shows she was tense beforehand, with a considerable upsurge in tension following the walk. The enforced walk had a marked effect on mood. Pleasant mood (happiness and calmness) decreased and unpleasant mood (tension and depression) increased.

The coping strategy questionnaires for the week leading up to the first testing session and the hours and minutes before she entered the chamber for the first time revealed a predominance of strategies focused on managing emotions resulting from situations. For example, Kirsty reported coping by ‘accepting what was happening’ and ‘trying to see the positives’ a lot.

In reviewing these results, Kirsty explained that she had experienced a considerable amount of work stress in the weeks leading up to the first testing session.

The coping pattern demonstrated by Kirsty indicated that she perceived a lack of control over the situations she faced – an interpretation supported by her own perceptions and beliefs. The combination of different stressors led to Kirsty becoming increasingly frustrated: she had a heavy workload and her training had not gone as well as she would have liked(6).

When we discussed the first set of mood and coping data with Kirsty, we gave her guidance on engaging coping strategies intended to change or gain control over any challenges she encountered. In particular, she was advised to utilise planning, asking for help, and making the situation better as coping strategies.

A second emphasis of the intervention was managing unpleasant mood states resulting from extreme cold. Our advice was partially guided by findings from our research with a South and North Pole explorer(4,5) who described how she managed feelings of being extremely cold. She indicated that if she attended to her feelings, she would concentrate on ways of getting warmer. Kirsty was encouraged to use strategies such as mentally picturing herself completing the North Pole marathon and successfully managing all physical, emotional and cognitive responses to the conditions.

Kirsty’s mood profile was very different during the second run in the environmental chamber (see figure 2). Specifically, she maintained pleasant mood states and low tension throughout. During the period of enforced walking, she sang loudly as a strategy to dissociate from the cold.

The coping data taken in the chamber 90 minutes into the second test showed that her use of strategies focused on managing the situation remained consistent with those used at that point in the previous week. However, her use of strategies focused on managing emotions showed variation. For example, her use of humour reduced (from a lot to a little), acceptance reduced (from a lot to not at all), while positive reframing reduced (from a medium amount to not at all). These changes indicate that there were fewer emotional consequences requiring management. This finding is supportive of the mood data and comments made by Kirsty following test completion.

The conclusion derived from the lab-based work indicated that Kirsty believed she could cope with the cold, even if this involved being unable to maintain warmth through running. She had tested her equipment in appropriate conditions. Other competitors’ preparation strategies have included a range of different approaches; for example, one athlete exercised in an industrial freezer!

Take-home message

Completing the North Pole marathon requires considerable preparation. However, while this isa seemingly obvious statement, it is important to emphasise that preparation must involve more

than simply trying harder for longer. In this article, we have emphasised the importance of developing specific training programmes to tackle specific challenges – including psychological ones.

The environmental chamber was used to develop a meaningful understanding of how difficult running at -25°C can be, but also to develop confidence that Kirsty’s running kit was warm enough and not overly restrictive. In addition, she learned to manage unpleasant emotions brought on by uncertainty in controlled conditions and developed strategies to work independently of those emotions.

References

- Lane et al (2007) ‘Validity of the Brunel Mood Scale for use with UK, Italian and Hungarian Athletes’ in Lane (ed) Mood and Human Performance: Conceptual, Measurement, and Applied Issues, 119-130. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science.

- International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 1997; (4) 92-100.

- Lane (2007) ‘The rise and fall of the iceberg: development of a conceptual model of mood-performance relationships’ in Lane (ed) Mood and Human Performance: Conceptual, Measurement, and Applied Issues, 1-34. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science.

- ‘Mood state changes during an expedition to the South Pole: a case study of a female explorer’ in Lane (ed) Mood and Human Performance: Conceptual, Measurement, and Applied Issues, 217-231. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science.

- Wilderness and Environmental Medicine 2007; (18) 2, 127-132.

- ‘Does all play and no work make Jack a dull boy?’ Sports Performance Bulletin 2008, issue 255, p8.

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.