You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Calling it a day: what next for retired athletes?

Retiring from competition is a big deal for professional or lifelong athletes. SPB looks at new research on how retirement can impact health and well being, who is most risk and how athletes can try to manage any fallout

The laws of physics dictate that the passage of time is always accompanied by an increase in something called ‘entropy’. In simple terms, entropy is a measure of disorder in a system, and as time passes, disorder in a system (and indeed, in the universe as a whole) always increases. In a biological organism such as the human body, which relies on intricate and precise mechanisms to main optimum biological function, increasing disorder is definitely a bad thing. But as the years pass, increasing disorder within cells arising from accumulated DNA damage and imperfect cell replication cannot be avoided. You of course know this process as aging.

There are a number of physiological changes that take place as we age, and while lifelong top-quality nutrition and exercise can dramatically slow these changes, as each decade passes, maximum performance potential declines. [For a more detailed discussion on aging and performance, readers are directed to this article.] The upshot of these changes is that over time, endurance, strength and flexibility all decline, while aches and pains become ever more common and frequent. These unavoidable physiological changes mean that at some point, even the most committed athletes are forced to hang up their shoes and retire from competition.

Lifelong athletes and the consequences of retirement

Any big change in lifestyle, routine or habits requires mental adaptation to new circumstances(1). But while much is talked about the psychological well being of athletes in training (and the link with performance), what happens to athletes – especially those involved in lifelong training – when they hang up their shoes and retire? Although this is not a prominent topic in sports science research, a number of studies on the impact of retirement in professional athletes who were previously competing at a high level have been carried out.

In particular, research shows that retirement from sport can be psychologically distressing, particularly when it is sudden and involuntary(2). This is perhaps not surprising; it’s one thing to make a voluntary decision to retire from sport. But it’s another when circumstances force retirement on you, for example following a career-ending injury. Regardless, research also shows that whatever the circumstances of retirement, many athletes find that the transition from ‘athlete’ to ‘non-athlete’ is a difficult one, especially for athletes where sport has played a major role in their lives and helped define who they are(3).

Professional athlete retirement

Although we all have to retire from sport eventually, let’s not forget that professional athletes typically retire from sport much earlier than amateurs. This can happen because athletes feel they’ve reached their maximum potential and want to wind things down, or because injuries mean they can no longer make the team. Or even because the sponsors decide they want some new faces around! Whatever the reason, career termination in a professional athlete results in a loss of income, which means that the athlete is not only mentally unprepared, but also potentially financially unprepared for a life outside of sport(4) However, it should be said that retirement from professional sport is not always a negative experience; some retired professional athletes have reported that voluntarily leaving behind the high and ongoing physical and psychological demands of sport by retiring was actually a form of relief(5)!

Health consequences of athletic retirement

Major life events such as bereavement, moving house, divorce etc are known to have a negative impact on mental and physical health(6) so it’s not unreasonable to ask if an athlete retiring from sport (which can profoundly impact daily routines, sense of identity, social identity and friendship networks, levels of motivation and ambition) can also experience such negative impacts? According to the research, the answer to this question is most definitely ‘yes’, and very significantly so.

Studies show that for professional athletes, the transition from competitive sport to retirement can contribute to depression, anxiety, disordered eating, substance abuse, and even suicide(7). Indeed, a study on former elite male power sport athletes reported that suicide rates were 2–4 times higher for former male athletes than the general male population(8), possibly because men often identify more strongly with their athletic role than do women(9).

In addition, research into professional soccer players has demonstrated that these conditions, combined with pondering the loss of a career or lifestyle, can result in significant sleep problems(10). The issue of sleep problems and disordered sleep patterns in retired athletes is known to be a problem among retired National Football League (NFL) players, where there has been a major focus of sleep research. In retired NFL players, sleep apnoea is 2.5 times more likely to occur than in age-matched controls(11,12). Moreover, a systematic review study or retired elite athletes found that 20.9% of all former athletes studied suffered from sleep disturbances, insomnia, or generally disordered sleep patterns (all of which are known to negatively impact health)(13).

What about amateur athletes?

Nearly all of the research to date on athletic retirement and health has focussed on elite competitors who competed at an elite/international level or world class level. This means that there’s relatively little knowledge on the impact of retirement in athletes at other competition levels (eg national and highly trained athletes, competitive amateurs and recreational athletes with a long history of sport involvement).

Are non-elite athletes impacted in the same way in terms of mental health and sleep issues? And if so, how do factors such as the sex of the athlete, level of pre-retirement competition/achievement, and time elapsed since retirement affect the likelihood of health problems? We might assume that the higher the level of competition, the greater the priority placed on sport during an athlete’s career, and therefore the greater the risk of sleep and mental health problems following retirement. But is this actually true and might you be at risk following retirement?

New research

For some answers to the above questions, we can turn to new research by a team of Aussie scientists specializing in sports psychology and sleep health(14). Published in the journal ‘Frontiers in Psychology’, the aim of their investigation was to determine how competition level, sport type, level of commitment, length of retirement and biological sex, and were associated with symptoms of sleep and mental health disorders in former athletes.

In this study (which was actually part of a larger, more general study on athlete mental health and sleep patterns), 173 former athletes (87 women and 86 men) all of whom had retired from sports competition within the last 20 years were surveyed. The breakdown of athletes included differed markedly from previous studies on this topic (using elite/world class retirees), with nearly half the athletes (45.7%) being categorized as amateurs, 28.3% competing at university/college level, 15.0% at semi-professional level and only 11.0% who had been competing at professional level.

The athletes came from a wide variety of sports, with soccer, rugby, swimming and weightlifting particularly well represented. Interestingly, although only 11% of the athletes had been competing at professional level, over two thirds (67.1%) described the priority they placed on sport prior to retirement as ‘high’, rather than ‘medium’ or ‘low’. For a full breakdown of the athletes’ sports, ages, countries of residence, and years of retirement, readers are directed to this table.

What they did

Using sporting organisations from Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, South Africa, United Kingdom, and US, adult athletes from all sports, genders, and levels of competition, at any stage of their career were invited to participate in a voluntary survey. This survey consisted of a combination of a number of scientifically validated questionnaires used to assess well being, sleep health, anxiety and depression. These were as follows:

· Personal Wellbeing Index-Adult (PWI-A) questionnaire(15)

· Athlete Sleep Screening Questionnaire (ASSQ)(16)

· Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale-Revised (CESD-R) questionnaire(17)

· Generalised Anxiety Disorder Assessment (GAD-7)(18)

The athletes’ responses to the personal well being questionnaire were scored and recorded as either ‘normal’ or ‘compromised’. For the remaining three questionnaires, scoring took place, with the athletes being placed in categories ranging from ‘none’, ‘minimal’, ‘mild’, ‘moderate’ and ‘severe’. Statistical analysis was then performed to see how the athletes’ scores were related to their own characteristics – ie age, body mass index (BMI), gender, recency of retirement and priority level placed on sport. Why was the relationship between BMI and sleep/mental health assessed you might ask? This is because in sleep disorders such as sleep apnoea, it is known that increased neck circumference (suggesting larger than average upper body musculature) and BMI are risk factors for this condition(19).

What they found

The key findings were as follows:

· Among retired athletes, being female or being younger was associated with an increased risk of suffering anxiety symptoms.

· Retired athletes who had a higher body mass were more likely to suffer disordered sleep patterns, sleep apnoea (irregular breathing during sleep) and to score lower on measures of well being.

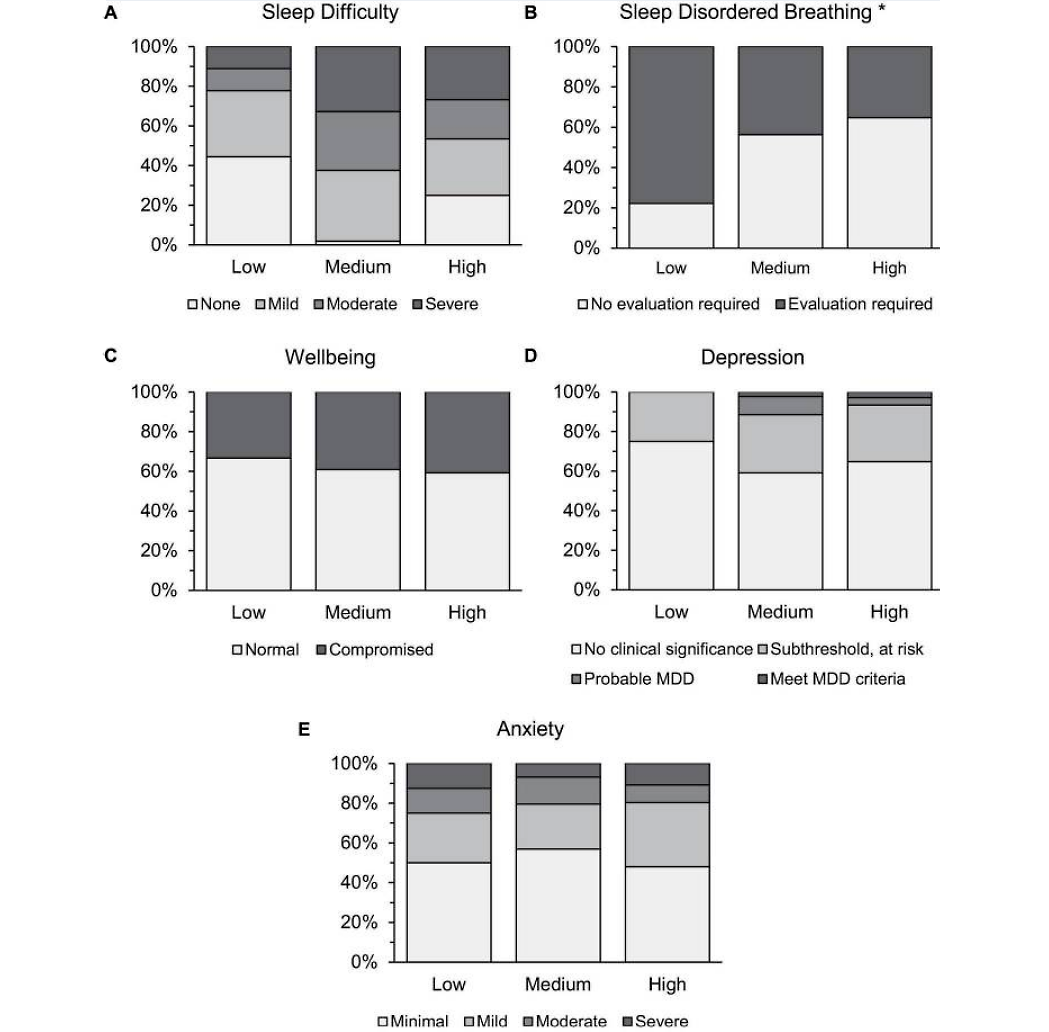

· Contrary to expectations, retired athletes who had previously placed a great deal of importance on their sport were at no greater risk of suffering adverse health or sleep patterns (see figure 1). Indeed, those who had subjectively placed a lower priority on their sport actually scored worse for sleep quality, particularly for sleep disordered breathing.

· Again, contrary to expectations, there was no association between how recently athletes retired and adverse health or sleep patterns.

Figure 1: Athletes’ sport priorities and subsequent health/sleep problems following retirement

The researchers expected to see more health and sleep problems in athletes who placed a ‘high’ priority on their sport while competing, and least in those where sport was a ‘low’ priority. However, no such trend was observed; indeed the only significant finding was a greater prevalence of sleep disordered breathing in the low priority athletes.

Implications and advice for athletes

What do these findings mean for retiring athletes, especially amateur and recreational athletes who make up the bulk of sports participants? Firstly, we can conclude that it’s not just pro athletes who are negatively impacted by retirement; if you’ve been competing at an amateur level for many years or even just been a recreational athlete who takes fitness seriously, you may well find that retirement impacts your well being and sleep quality. Why aren’t pro athletes (who experience loss of income and status) affected more than amateur athletes? We can only guess but one reason could be that pro athletes often turn to recreational sport or fitness activities pursued at a lower level following retirement, thereby sustaining a social network and the health/psychological benefits of exercise(20). By contrast, when amateur or recreational athletes cease their sports, they may not be able to sustain regular exercise patterns (for example due to injury).

Another key finding was that problems following retirement are not limited to the period immediately after retirement as time elapsed since retirement didn’t affect the susceptibility of athletes to health and sleep issues. The implication here (although untested) is that when athletes who retire experience problems such as depression, anxiety or poorer sleep, these issues may not pass in time, but instead become ingrained. This in turn suggests that retiring athletes may need to proactively seek support and add structure to their routines rather than letting things lapse. This could involve seeking out new activities and interests, making efforts to build a new social circle of friends and perhaps pursuing and practicing techniques that can promote mental relaxation and well being such as mindfulness training (see this article). These approaches may be especially relevant for younger and/or female athletes who seem to be more vulnerable to anxiety and depression following retirement.

Finally, the finding that retired athletes with higher body mass and/or BMI had increased sleep disorder symptoms is perhaps not surprising since sleep disorder conditions – particularly sleep apnoea – are known to be associated with increased body mass and obesity in the general population(21). Although it wasn’t analyzed, it’s possible that this finding and the finding that retired athletes who placed a low priority on sport (most likely recreational) overlap to an extent. In other words, we can take an educated guess that because recreational or casual athletes who retire are less likely to pursue another sport or form of exercise (because by definition, if they did, they wouldn’t be classed as retired), they are more likely to become sedentary and experience weight gain as a result.

Regardless of an athlete’s background and participation level, there’s a strong argument that younger retiring sportsmen and women should seek help and advice from sport science professionals (eg strength and conditioning coaches, nutritionists etc) so that they can develop the skills necessary for living a healthy lifestyle after sport. Older athletes, particularly those who have competed at amateur levels or pursued and recreational sport will probably already have a good idea of how to take care of the lifestyle basics. However, adopting some kind of goal-setting strategy that engages the athlete in new physical, mental and social activities (including finding new hobbies and pastimes) and healthy eating for life after retirement may be a useful option since research shows that such a strategy produces significant health benefits in the longer term(22). For retired or retiring athletes who want to learn more about the psychology of aging and real life stories about coping with athletic retirement this paper (while a rather technical read) is extremely informative!

References

1. Obes Rev. 2020 Jul;21(7):e13014. doi: 10.1111/obr.13014

2. Front. Psychol. 13:868614. 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.868614

3. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2017. 63 598–601

4. J. Pers. Interpers 1999. Loss 4 269–280.

5. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2017. 52 924–939

6. J Affect Disord. 2022 Feb 15:299:298-308

7. Front. Psychol 2022. 13:868614. 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.868614

8. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 24 1000–1005

9. Curr. Opin. Psychol 2017. 16 118–122

10. BMJ Open 9 e030056. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030056

11. J. Occup. Environ. Med 2012. 54 816–819

12. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2017. 9:31

13. Br. J. Sports Med 2019. 53 700–706

14. Front Psychol. 2024; 15: 1350925

15. International Wellbeing Group (2013). Personal Wellbeing Index, 5th Edn. Potomac, MA: International Wellbeing Group

16. Br. J. Sports Med 2016. 50 418–422

17. Eaton W. W., Smith C., Ybarra M., Muntaner C., Tien A. (2004). Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: review and revision (CESD and CESD-R)

18. Arch. Intern. Med 2006. 166 1092–1097

19. Clin. Sports Med 2005. 24 329–341

20. Leisure Stud 2021. 40 441–453

21. Postep. Psychiatr. Neurol 2023. 32 96–109

22. PLoS One. 2023; 18(9): e0291683

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.