You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Marathon preparation: the real cost of a training disruption

Illness, injury or personal circumstances can cause unexpected disruption to a marathon training program. But what length of disruption will materially affect your marathon time, and how should this inform your training and racing strategy?

For most amateur and recreational runners, training for a marathon is a bit like a balancing act. On the one hand, more miles and longer, harder training sessions can build the necessary fitness and resilience to complete the distance and complete it in a good time. On the other hand, the higher the training distance and intensity, the greater the chance of a running-related injury or illness. Running related injuries occur when the training load exceeds the recovery capacity of a particular runner, which itself depends on the runner’s training background and his/her unique physiology(1). Novice runners are at particular risk(2). Illness, especially upper respiratory tract infections, can occur as a result of the inevitable training-induced immune suppression that occurs when training loads are high and sustained(3).

Building in protection

A good marathon training program will not only be individualized to the needs of the runner, it will also include periods when the runner backs off somewhat in his/her training, in order to allow a more complete recovery(4). This in turn can reduce the risk of sustaining an injury or coming down with a bug. For example, programs will often implement 4-week cycles of training and recovery, with an 3-week period of increasing training load following by a 1-week recovery period with less training intensity before moving on to the next 4-week block. As such, a typical marathon programme might cover 3–4 blocks of training with training load usually peaking around one month before race-day.

Spanner in the works

Despite their best efforts however, many runners fall victim to either injury or illness during a marathon build up(5), and are therefore forced to take a complete training break. At best, this disrupts training for a relatively short period of time, but in the case of a more serious injury, this disruption may even prevent runners from making it to race-day at all. In short, a massive spanner is thrown into the works.

When an unplanned and extended training disruption does take place, the first thing runners genrally want to know is what impact the disruption will have on the rest of their marathon build up and performance on the big day. “Will I still be able to race?” and “How will my race time be impacted by this layoff” are the two most asked questions. It turns out that’s a tricky question to answer.

While there have been a number of studies on the effect of periods of de-training on running fitness(6) (see this article on detraining), less is known about the frequency of training disruptions during a marathon training program, and their impact on subsequent marathon performance, especially among recreational runners. That’s because training programs rarely incorporate any extended periods without any training, and instead recommend that runners maintain a consistent training schedule, which almost always recommended for optimal marathon performance (7).

The real impact of training disruptions

To try and quantify the real impact of marathon training disruptions, a new study by a team of Irish researchers has investigated the frequency and performance cost of training disruptions, especially among recreational runners(8). Published in the journal ‘Frontiers in Sport and Active Living’, this study set out to assess the frequency, duration and performance cost of training disruptions, and the importance of training consistency, especially among recreational runners.

This was a retrospective study, which looked back at data gathered from 292,323 recreational runners who completed marathons during the period 2014–2017. These runners were all users of the popular running app, Strava. Although not a direct intervention study, this research makes for compelling reading since it gathered together a huge amount of data from a large number of runners, making it less prone to statistical errors and anomalies.

In total, no less than 15,697,711 individual running activities (ie individual training sessions) were assessed from 292,323 individual runners, who between them completed 509,979 marathons during the period 2014–2017. It should be noted however that the study only looked at runners who participated in at least one marathon event during this period; therefore, was not able to analyse data from runners who may have intended to participate in one or more marathon, but were unable to, because of injury, illness, or for some other reason.

How the analysis was done

The Strava data from all the 292,323 runners was broken down by the researchers to identify the following:

· Periods of varying durations in the 16 weeks before the marathon where runners experienced a complete cessation of training (a so-called training disruption).

· Runners who had completed multiple marathons including at least one disrupted marathon with a long training disruption of seven or more days and at least one undisrupted marathon where there were no training disruptions in the 16 weeks previously.

· The age, sex and ability of all of these runners to explore how these factors might affect the outcome of a training disruption.

Once these parameters had been collated, the researchers went on to calculate the performance cost of long training disruptions. This was determined as the percentage difference between a disrupted marathon (where training had ceased completely for more than seven days) and an undisrupted marathon, where there was a smooth uninterrupted training build up to the event. The analysis also compared the frequency and cost of training disruptions according to the sex, age, and ability of runner. In addition, the researchers looked at whether the disruptions occurred early or late in 16-week training period and how this influenced marathon times.

What they found

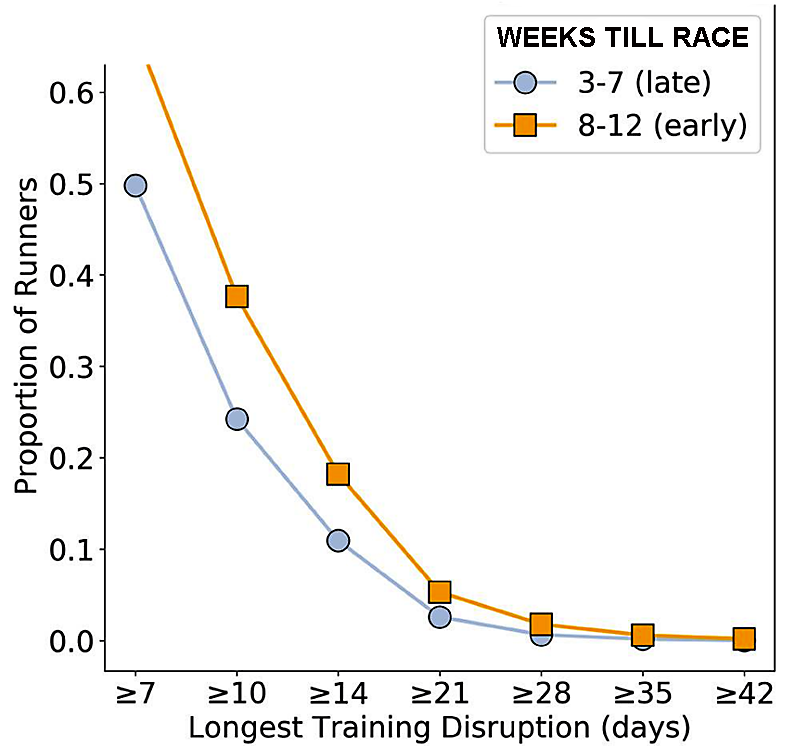

· Training disruptions were more common during the early stages of marathon training (8-12 weeks prior to race day) compared to the later stages (3-7 weeks prior to race day) – see figure 1.

· Over 50% of runners experienced short training disruptions up to and including 6 days, but longer disruptions were found to be increasingly less frequent among those who made it to race-day.

· Male runners, younger runners, or faster runners are more likely to experience disruptions of any given duration compared with females, older runners, or slower runners respectively. However, when these disruptions did occur, they were more likely to occur earlier in the training program – implying they were less likely to prevent these runners from completing the marathon.

· Runners who experienced longer training disruptions of 7 days or more suffered a finish-time cost of 5–8% extra (an extra 9-14 minutes on a 3-hour marathon) compared to when the same runners experienced only short training disruptions of less than 7 days.

· When they occurred, long (7+ days) training disruptions led to a greater finish-time cost for males than females. Faster runners also tended to experience a greater finish-time cost than slower runners.

Figure 1: Training disruptions early and late in the marathon training period

Blue dots = disruptions close to race day. Orange squares = disruptions earlier in the marathon training program. Short disruptions were far more common than long disruptions. However, disruptions of all lengths were less common later in training program as race day approached.

What do these findings mean for runners?

There’s a lot to unpack here, but the probably the most important finding is that for short (less than 7 days) interruptions to training, there was no significant negative impact on race performance. This is reassuring news because (also from this data) recreational runners are more likely than not to suffer a short training disruption at some point during their marathon training. A practical implication that follows is that when a short disruption occurs, runners should ‘relax’ and not try to ‘catch up’ by packing in extra training to make up for lost time, because this evidence suggests it’s not really needed.

Another key finding is that training disruptions were more likely to occur earlier in the marathon program than later on. This makes sense because this is when novice and recreational runners without an extensive marathon training background are subjecting their muscles, joints and tendons to new and unaccustomed training loads compared to the period before training commenced. Later in the program however, these muscle/tendon systems will have already had 2-3 months to adapt to the increased loading, so new injuries due to the unaccustomed training loads are less likely.

Another practical implication that follows is that runners should take extra care to not overload themselves during the early stages of their marathon training. This involves playing close attention to muscle niggles, aches and stiffness and acting accordingly by backing off a little on the training load rather than following a program blindly because that’s what’s written down in front of you!

When a more prolonged disruption of over 7 days occurs – for example due to an injury that takes time to heal – runners must understand that there will likely be a cost to their race time, especially if they are faster or younger runners. Although this study didn’t explore this aspect further, it’s reasonable to assume that the longer the disruption, the bigger hit to performance – eg, a 14-day disruption will incur a greater performance penalty than a 7-day disruption.

In practical terms, faster runners with previous marathon experience who are seeking a new PB but who suffer a more prolonged layoff during training should accept that their goal is less likely to be achieved. Complete novices and slow runners can take comfort that even a longer training disruption will likely not impair performance on the big day too much.

Of course, each runner and set of personal circumstances are different, so it’s impossible to be certain of these potentially negative outcome; however, by understanding that training disruptions do tend to have a performance cost, runners are less likely to be disappointed and become disillusioned. When training disruptions are of significant length and getting that PB is your main goal, another alternative is to treat the race in question more as a dedicated training session, and focus instead on getting that PB in a later race!

References

1. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2007 Oct;6(5):307-13

2. Sports Med. 2015 Jul;45(7):1017-26

3. Br J Sports Med. 2016 Sep;50(17):1043-52

4. Periodization: theory, methodology of training. Champaign: Human Kinetics; (2018)

5. Sports Med (Auckland, N.Z.). (2015) 45:1143–61 Eur J Sport Sci. 2021; 22(3):399–406

6. Eur J Sport Sci. 2021; 22(3):399–406

7. J Sci Med Sport. (2020) 23:182–8

8. Front Sports Act Living. 2022; 4: 1096124. Published online 2023 Jan 10

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.