You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Older athletes: weighty matters for knee health

Older athletes are vulnerable to knee osteoarthritis as the years tick by. The good news is that certain types of exercise can stabilize and even reverse the symptoms of this condition, but what works best? SPB looks at brand new research

Of all the joints in the body, it’s the knees that take the biggest hammering in most athletes. In runners, the knee joint is subjected to incessant pounding and impact shocks, which are transmitted through the knees. In field sports such as soccer, rugby, hockey and those played on the court such as tennis, squash basketball etc, the impact shocks are compounded by lateral and rotational torsion forces, which further load the structures in the knee.

Given these facts, it’s hardly surprising that knee injuries are the most common non-contact injury suffered by athletes such as soccer players(1) and runners(2). For athletes who suffer a knee injury, it can be a very frustrating experience as the time off training needed for rest and rehab can result in hard-won fitness gains slipping away. In the longer term, there’s more bad news because it’s also known that when knee injuries occur, especially serious injuries such as those to the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), the risk of developing chronic osteoarthritis in the knee is increased in later years(3).

Understanding osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis is a multi-factorial chronic disease, with approximately 240 million people worldwide diagnosed with the condition, predominantly knee osteoarthritis. Knee osteoarthritis is most common in the elderly, but can also occur in those who are young or middle-aged, particularly in individuals with a history of obesity(4). While osteoarthritis is most common in the knee joint, it can also affect the hips, hands, spine, and feet, leading to pain, stiffness, functional impairment, and reduced quality of life. For older athletes however, especially those who have a history of previous knee injury, it is the knee joint that is most vulnerable.

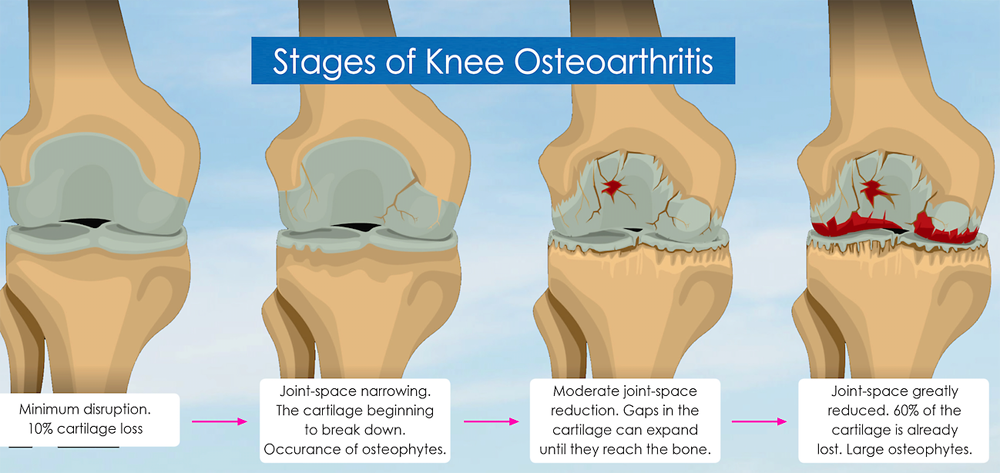

Osteoarthritis is characterized by the deterioration of the joints involving the articular cartilage (cartilage present on the joint surface where bones move across each other during movement), as well as the adjacent tissues (see figure 1)(5). In essence, osteoarthritis occurs due to a failure of the balance between destruction and reparation of joint tissue, whereby more tissue is destroyed than regenerated, and that which is regenerated is imperfect. This leads to a decrease in overall cartilage volume, poorer bone remodelling and weakness of the ligaments around the joint(6).

Figure 1: Schematic representation of knee osteoarthritis progression

When it occurs, knee osteoarthtis can cause a range of symptoms, from mild discomfort in the early stages to considerable pain and disability, especially in the elderly. In addition, there is typically reduced range of movement in the joint(s) affected and there may also be muscle weakness. For athletes of course, the early onset of knee osteoarthritis is most definitely unwelcome! In the initial stages, it might present as vague and mild aches and pains in the affected knee that typically come and go. However, as it progresses, the sensations of discomfort inevitably become more apparent – often to the point where training starts to become interrupted.

As there are so many conditions that can result in knee pain, a diagnosis of osteoarthritis is essential (because this affects the treatment and management path forward). The starting point for a diagnosis is an X-ray radiograph, which is the most common scan used by physicians. Unfortunately however, there is a poor correlation between radiographic findings and the actual clinical symptoms you might be experiencing(7,8). For that reason, an MRI scan (which reveals much more detail in the surrounding soft tissues) is more useful as a diagnostic tool(9).

Managing knee osteoarthritis

As the years tick by, most older athletes will likely experience some degree of osteoarthritic degeneration in the knee joints. For many hopefully, the amount of degenerative change will be quite limited, meaning the athlete can maintain normal knee function well into older age with little or no discomfort. Inevitably however, some athletes will experience more significant osteoarthritic changes in one or both knee joints, and this may begin to impact performance – or even the ability to train normally. In such cases, managing the condition is essential in order to maintain knee function and minimize further degenerative changes.

One of the myths about joint health that is still popular today is that joints ‘wear out’, and that athletes or anybody else who is wanting to manage osteoarthritis in the knee joint therefore needs to rest, or engage in gentle exercise only. However, as we explained above, the knee joint – whether there’s osteoarthritis present or not – is a dynamic system where old or damaged tissue is constantly being replaced with new healthy tissue. The key is that in a knee joint suffering progressive osteoarthritis, the process of regeneration with healthy tissue starts to lag behind the process of accumulated damage. When trying to manage this condition then, the goal is to try and speed up the regenerative process as much as possible.

The role of exercise training

When it comes to managing knee osteoarthritis, exercise therapy is recognized worldwide as a first-line treatment strategy because it can aid joint tissue regeneration(10). Common types of exercise therapy encompass a variety of methods, including aerobic exercises, aquatic exercises in the pool (reducing weight through the knee joint) and mind-body exercises - each with its unique benefits(11) Surprisingly perhaps, one of the most common and effective rehab/prevention methods to combat knee osteoarthritis is resistance training.

Over the years, a large body of evidence has shown that certain types of resistance training of the legs in order to load the knee joint can enhance muscle strength, improve joint stability and function, and alleviate joint loading, all of which slow down the further degeneration of knee cartilage and improve pain symptoms and the quality of life for patients(12-17). But what kind of strength training is most effective in improving or maintaining function in athletes who are beginning to experience knee osteoarthritis?

In the physiotherapist’s clinic, the strength training mode of choice is ‘isokinetic’ training, where the knee joint is loaded and worked at a constant velocity(18). This is partly due to the fact that isokinetic training offers a safe and controlled method of loading the affected joint(s). There’s also good data in the literature to support its use. The problem however for athletes seeking to perform strength training is that specialised equipment is required, which is very often difficult to access.

Therefore, some clinicians or physiotherapists instead recommend more common strength training modes such as ‘isotonic’ muscle strengthening (normal strength training working against a load provided by a weight) or isometric muscle strengthening (holding a fixed position while the knee joint is loaded). But how effective are these alternative modes really and can they really help reduce pain, improve knee function and help prevent further knee joint deterioration?

New research

A new study by a team of Chinese researchers, and which has just been published in the journal ‘PloS One’, has tried to answer this question(19). This research took the form of a systematic review and meta-analysis, where all the previous research on this topic was gathered together and the data pooled, in order to come to much more robust conclusions than would be possible from a single study.

The researchers looked for all the previously published studies involved patients with a diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis, where treatment groups included isokinetic, isotonic or isometric strength training for the legs, and where there was a control group that received standard knee osteoarthritis treatments such as physical therapy, rehabilitation or pharmacological interventions such as anti-inflammatory painkillers.

What they did

A total of 11,130 articles were obtained from the initial search. However, when unsuitable studies were removed (eg duplicates, poor relevance, high amounts of bias etc), this was whittled down to just 12 studies involving 753 patients with a treatment duration of three to eight weeks, and where the interventions included the three types of strength training as well as standard knee osteoarthritis treatments. Readers can find a detailed description of these 12 studies in table 1.

When the pooled data was analyzed, the researchers looked at the outcomes of each training mode in terms of visual analogue scores for pain assessment (ie perceived pain on a scale of 1-10 and how it improved), functionality of the knee joint using a tool known as the Western Ontario and McMaster University Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC)(20), and also measurements of knee-joint peak torque and strength for muscle strength assessment.

What they found

Three key findings emerged from the analysis:

1. All three forms of resistance training – isokinetic, isotonic and isometric – produced superior results compared to conventional treatments using painkillers, physical therapy etc. This was true regardless of which metric was being measured – ie knee pain, knee function or knee strength.

2. Of the three resistance modes, isokinetic training did indeed produce the best results in all measures of improvement.

3. When it came to pain scores and strength improvement, isotonic training (ie using weight resistance) was superior to isometric (static position) training. However, in the knee functionality score, isometric training was slightly superior to isotonic training.

The researchers concluded that although the best improvements were seen with isokinetic training, the improvements with isotonic and isometric resistance training were still very significant, which means these two training types can be confidently recommended in a non-physio setting, and both being better than conventional treatment types.

Practical implications for athletes

If you’re an older (50+) athlete experiencing chronic, low-level knee pain without any obvious causal injury, it’s possible that the discomfort you feel is due to the early stages on knee osteoarthritis, particularly if you have a history of knee injuries in the past. Typically the symptoms you experience will change in intensity without any apparent reason – sometimes almost fading away completely, and at other times becoming much more obvious.

The first port of call should be a physician or clinician who can perform a proper assessment and diagnosis, which may include X-ray imaging or MRI scans. By ruling out the presence of an injury and looking at positive scan results, they will be able to confirm knee osteoarthritis. At this point, it’s important to remember that almost all knees of older athlete will show some signs of age-related degeneration, and also that what the X-ray or MRI image shows often doesn’t necessarily correlate to degree of symptoms. Therefore, athletes should not lose heart when the presence of (a degree of) knee osteoarthritis is confirmed! All it means is that you need to train sympathetically, avoiding movements that overload the knee or put it under twisting/torsional stress, and invest time in management.

The study above (along with other data) suggests that rather than use pain killers or therapies such as massage, strength training the legs should be your go-to treatment/management strategy. If you have access to any isokinetic leg training equipment, choose that preferentially. If not, don’t worry because good old fashioned weight training will get you a long way. As the author of this article, I can anecdotally report that earlier this year, I had been suffering right inner knee pain for a few months that wouldn’t settle. Eventually, it began to interfere with my ability to train, or even walk on bad days. A visit to a physiotherapist and an X-ray revealed some early signs of knee osteoarthritis. However, after embarking on a regular program of carefully executed squats, the pain completely resolved within eight weeks, and I am still pain-free!

Finally, while resistance training should be your number one priority, don’t forget about the role of diet and nutrition. Over the past three years or so, there’s been a surge in research looking at key nutrients in combating osteoarthritis. The following nutrients are now believed to be especially helpful thanks to their anti-inflammatory properties:

· Omega-3 oils, which can result in the reduction of cartilage destruction and inhibit pro-inflammatory pathways(21).

· Curcumin (from turmeric), which has been found to relieve pain, improve joint mobility and stiffness, and reduce the need for medication in osteoarthritis patients(22).

· Collagen peptides, which can help improve symptoms by providing the amino acids needed for cartilage regeneration(23).

· Ginger, which can significantly decrease inflammatory markers in osteoarthritis(24).

· More generally, research shows that a healthy ‘Mediterranean-type’ diet with a minimum of processed foods can help improve pain, stiffness, inflammation, and biomarkers of cartilage degeneration in osteoarthritis(25).

For a more general discussion on how natural nutrients can be used by older athletes to combat inflammation-related conditions, this article provides a lot of useful information!

References

1. J Clin Med. 2023 Aug 26;12(17):5569

2. Ann Transl Med. 2019 Oct;7(Suppl 7):S249

3. J Orthop Translat. 2019 Aug 6:22:14-25

4. Ann Rheum Dis 2014. 73(7):1323–1330

5. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research 2019. 31:1049–1056

6. Br Med Bull 2013. 105(1):185–199

7. Radiology. 2006;239(3):811-7

8. Radiology. 2005;237(3):998-1007

9. Nagai K, Nagai NT, Nagai FFH: ‘The diagnosis of early osteoarthritis of the knee using magnetic resonance imaging’ Annals of Joint 2018

10. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019;27(11):1578–1589

11. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2016;59(3):190–195.

12. JAMA. 2021;325(7):646–657

13. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51(10):1977–1986

14. Phys Ther Sport. 2018;32:22–28

15. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25(8):1238–1246

16. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;17(1)

17. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2015;43(1):14–22

18. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2016;59(3):207–215

19. PLoS One. 2024 Dec 5;19(12):e0309950

20. Clin Rheumatol. 1986;5(2):231–41

21. Nutrients. 2024 May 28;16(11):1650

22. Phytother Res. 2024 Jun;38(6):2875-2891

23. Medicines (Basel). 2023 Sep 1;10(9):50

24. Nutrients. 2022 Apr 12;14(8):1607

25. Nutrients. 2023 Jul 6;15(13):3050

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.