You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Alcohol and recovery: drinking to success or excess?

Sir Winston Churchill was a brilliant war-time leader but with a love of alcohol that would be frowned on today. Churchill admitted he relied on alcohol; as well as always having a glass of whiskey by his side, he drank brandy and champagne at both lunchtime and dinner! However, it never seemed to affect his capacity to function; as Churchill himself put it: “I have taken more out of alcohol than alcohol has taken out of me.”

When it comes to endurance performance of course, the drinking habits of Churchill would be a complete no-no for any athlete who cares about health or performance. However, what about much more modest levels of alcohol consumption – for example, those within the governments current healthy drinking guidelines? In particular, what are the effects on recovery of consuming alcohol during the period following training or racing – for example during a post-event celebration?

Alcohol and sport

Alcohol is the most commonly used recreational drug globally, and its consumption - often in large amounts - is deeply embedded in many aspects of Western society. Athletes are not exempt from the influence alcohol has on society and some studies have shown that they often consume greater volumes of alcohol through bingeing behaviour compared with the general populationSports Med. 2014 Jul;44(7):909-19. Having said that, many of the studies into alcohol consumption in athletes have been carried out among younger athletes – often in a university setting. If you’ve attended university, you’ll no doubt be aware that most social events involve alcohol...Also, there’s additional evidence that certain sports and personality types are more likely to consume higher levels of alcohol. For example, one study found that team-sports players were more likely to be categorised as hazardous drinkers than individual sports players such as runners and swimmersAlcohol. 2015 Sep;50(5):617-23. In short, if you’re a rugby or football player, you’re more like to get a few bevies in after training or matches than if you’re a runner/cyclist/triathlete!

That said, alcohol is still a very common component of post-event celebrations in endurance sport as evidenced by postrace beer tents, free drink vouchers on bib numbers, or casual meetings at a local pub or restaurant following an event. And many athletes enjoy a beer or wine after a hard effort out on the roads or on the track; it can signify a reward for all of the training you’ve done or how well you raced and is also an opportunity to socialise with your fellow athletes off the race course.

Alcohol, health and exercise

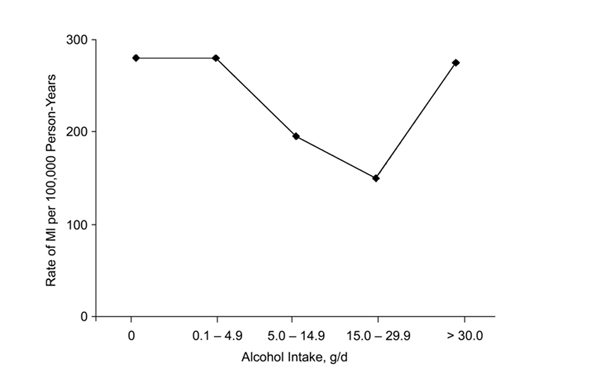

Although international guidelines suggest a light-to-moderate alcoholic beverage consumption (around 130–250mls of wine per day – 2 units) can be beneficial for cardiovascular healthEuropean Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR) Eur Heart J. 20162016 pii: ehw106 J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(24):e44–e164 Arq Bras Cardiol. 2010;95(1 Sul):1–51, it is known that higher alcohol intakes (more than around 31 grams per day – 4 units) may have harmful effects on the cardiovascular system, including an increase in blood pressure, strokes, heart disease and even increase the risk of some cancersHypertension. 2015;66(3):517–523 Am J Hypertens. 2005;18:276–286 J Hypertens Suppl. 1989;7(6):S20–S21. In other words, there’s a ‘U-shaped curve’ relationship between alcohol consumption and the risk for many cardiovascular conditions (see figures 1 and 2). Notice that the ‘sweet spot’ for women in figure 1 is limited to a maximum of around 2 units per day, whereas for men, the maximum limit is around 4 units per day. Also notice that for men following an otherwise healthy lifestyle (taking exercise, good diet and non smoking), 2-3 units of alcohol per day actually confers a lower risk of myocardial infarction (heart attack) than does one drink per day or complete abstinence!Figure 1: Alcohol intake and all-cause mortalityJ Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(11):1009-1014. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.089

Figure 2: Alcohol intake in men following a healthy lifestyleArch Intern Med. 166 2006:2145-2150

Figure 3: How many units are in your drink?

Alcohol and recovery

While it’s true that there are some health benefits that may be associated with moderate alcohol consumption, there are other, performance-related factors related to alcohol that you should bear in mind the next time you reach for a chilled post-workout beer. The main concern is the effect of post-exercise alcohol on the recovery process, which can be impaired even with modest amounts of alcohol. There are a number of reasons why this is the case including:- Hydration – Alcohol is a diuretic, which means that drinking alcoholic beverages after training or racing is likely to cause your body to lose more fluid overall than is contained in the beverage you are consuming.

Unless you consume additional non-alcoholic drinks, or the alcoholic beverage is quite weak (more later), you will struggle to fully replace the fluid lost during exercise and the resulting dehydration may well leave you feeling tired, sick, and sore the next day. - Glycogen replacement – In addition to rehydration, replenishing depleted muscle and liver glycogen after exercise is vital for recovery. Alcohol however can dramatically inhibit the re-synthesis of liver glycogen stores, and may also impair muscle glycogen storage - some research has shown that it takes nearly twice as long to replace glycogen stores in athletes who have consumed alcohol compared to those who have notAm. J. Physiol. 1998;275:897–907 Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1998;22:437–443 Metabolism. 1978;27:97–106. Because glycogen is your body’s 5-star fuel, any shortfall or delay in glycogen replenishment can have profoundly negative consequences for subsequent training or competition. Some of this effect may also be due to the displacement of post-exercise carbohydrate intake in favour of alcohol intake; contrary to popular belief, beer and wine are not significant sources of carbohydrates and contribute very little to carbohydrate reloading following exercise.

- Protein synthesis – Some research suggests that post-exercise alcohol ingestion suppresses the anabolic (muscle building) responses in muscles and may therefore impair recovery and adaptation to trainingPLoS One. 12;9(2):e88384, 2014. This effect seems to occur even when protein is ingested with alcohol. Over the long term, this could have a negative effect on performance.

- Post-exercise muscle soreness – Following particularly long or strenuous workouts, some muscle soreness is inevitable. However, post-exercise alcohol may exacerbate this effect. It’s well known that icing muscles following soreness-inducing exercise reduces the resulting soreness, because ice constricts blood vessels and reduces swelling/inflammation. In contrast, alcohol is a ‘vasodilator’, increasing blood flow through muscles – ie produces the opposite effect.

- Sleep – In addition to the effects above, alcohol consumption has been linked to reduced sleep quality. In particular, heavy alcohol use is associated with reduced sleeping hours, resulting in a reduction in lower-body power output the morning after a drinking sessionJ Sci Med Sport. 18(3):268-71, 2015.

- Cognitive effects – Higher intakes of alcohol are known to adversely impact concentration the next day; this can have a negative effect on cognitive and motor function, which may lead to an increased risk of injury in sports where motor skills, balance and coordination are important.

Figure 4: alcohol and recovery

CASE STUDY: Henry Rono

Henry Rono was a brilliant track athlete – but one who was no stranger to a beer or two. The peak of Rono’s running career was the 1978 season. In a span of only 81 days, he broke four world records: the 10,000 metres, the 5000 metres, the 3000 metres steeplechase, and the 3000 metres - an achievement unparalleled in the history of distance running. He lowered the 10,000 metres record by almost 8 seconds, the 5000 by 4.5 seconds, the steeplechase by 2.6 seconds, and the 3000 by a full 3 seconds. In the same year he also won the 5000 and 3000 metres steeplechase gold medals at the Commonwealth Games.

But even more remarkable was that Rono achieved all this while consuming amounts of alcohol that would be considered way too high by today’s standards. After enrolling at Washington State University, in 1976, and struggling to settle in, Rono began drinking pitchers of beer every night until 2am, then rising early for a morning run. As he recalled in his memoirs: “On April 8, 1978, I spent most of that morning trying to shake off a hangover,” but he then went on to smash the 5000 metres world record, at a race in Berkeley, California. In the next eighty days, Rono broke three other world records, an astonishing feat. Rono wrote that his drinking didn’t hamper his running performance, and may even have strengthened him mentally. As he put it “Learning to run with a temple-thumping hangover taught me something about discipline, and how to put mind over matter, and focus beyond my physical pain, no matter how excruciating.”

Talking about Rono’s astonishing feats, Tim Noakes, a professor of exercise science and one of the world’s leading authorities on brain, fatigue and exercise performance agrees that the brain is the ‘ultimate determinant of performance’. As Noakes commented, “At the time, Rono thought that alcohol had no effect on his running. He perceived himself to be the best athlete in the world, and ran accordingly. It’s a mental attribute. And that self belief is part of the reason why the Kenyans have been so dominant in distance running.” However, Noakes also noted that while long training sessions may help a runner burn off toxins, drinking more than two beers a day usually harms performance’. He also doubted Rono’s argument that drinking taught him discipline, and added that ‘belief takes you only so far’. As if to confirm this, Rono eventually lapsed into alcoholism and depression for two decades - and even became homeless for more than a year. He did turn his life around though and now coaches athletics in Albuquerque.

Rono’s alcohol problems weren’t unique in Kenyan running; at least three top Kenyan runners with alcohol problems have died in recent times, including Paul Kipkoech, a world champion in the 10,000 metres, who was just 32 when he died. The most likely explanation for this phenomenon is that unlike in other top running countries, such as Ethiopia, Kenyan athletes were not routinely closely monitored by the country’s athletics federation. In particular, the combination of poor education, overnight riches, and demands from families and neighbours may have made top Kenyan runners particularly vulnerable to alcohol abuse.

How much is too much?

The easiest way to ensure that alcohol doesn’t interfere with your recovery is simply to avoid it during the post-exercise recovery period. But given that sport is often a social activity, and many athletes enjoy a beer or glass of wine with sporting friends after training or racing, you might be wondering how much and what type of alcohol it’s possible to drink without significantly harming your recovery.There’s no simple answer to this but as a rule of thumb, the more time that elapses after exercise before alcohol is consumed, the better – especially if you take that opportunity to consume some good recovery nutrition such as a carbohydrate drink with added protein and electrolyte minerals.

Another simple rule is that the less alcohol you consume, the less chance of hindering recovery. In a 2014 review study, researchers concluded that if athletes do consume alcohol after sport/ exercise, ‘a dose of approximately 0.5 grams per kilo of bodyweight is unlikely to impact most aspects of recovery’Sports Med. 2014 Jul;44(7):909-19. For an 80kg athlete this equates to 40 grams, or 5 units. This might seem generous but for a 50kg athlete, this would amount to only 3 units. Remember too, if you are female, you will metabolise any alcohol ingested less efficiently than a male of the equivalent weight.

There’s also good evidence to suggest that weaker alcoholic drinks may have much less of a negative impact on recovery – especially rehydration. In one study, subjects completed four separate trials whereby they exercised on a stationary bike until they were 2% (significantly) dehydratedInt J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2013 Dec;23(6):593-600. During the hour after exercise, they consumed four different beers (the amount of beer being equivalent to 150% of the body mass each subject had lost during exercise – see figure 5):

- A low-alcohol beer (2.3% by volume)

- A low-alcohol beer (2.3% by volume) with added sodium (25mmol per litre) – a key hydration electrolyte

- A full-strength beer (4.8% by volume)

- A full-strength beer (4.8% by volume) with added sodium

Figure 5: Alcohol and sodium consumed during hydrationInt J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2013 Dec;23(6):593-600

In a further study by the same researchers, the experimental protocol described above was repeated but this time usingInt J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2015 Jun;25(3):262-70:

- A low-alcohol beer (2.3% by volume) with added sodium (25mmol per litre)

- A low-alcohol beer (2.3% by volume) with added sodium (50mmol per litre)

- A mid-strength beer (3.5% by volume) with added sodium (25mmol per litre)

- A mid-strength beer (3.5% by volume) with added sodium (50mmol per litre)

PUTTING IT INTO PRACTICE

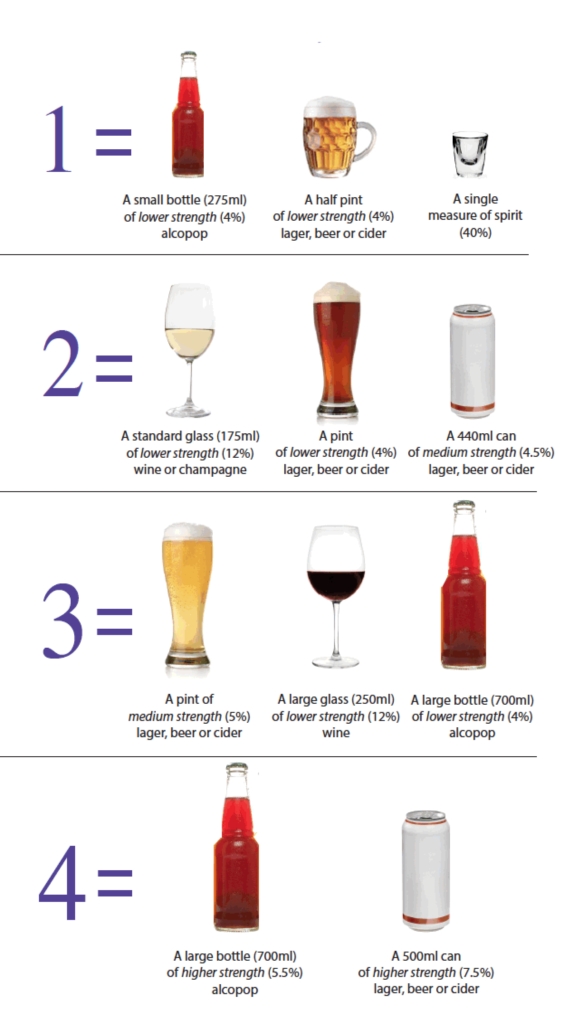

What do the latest findings on alcohol and recovery mean in practice for endurance athletes, and how do they fit with health recommendations? First of all, let’s start with some key points that all athletes should bear in mind, regardless of the requirements for recovery:- The latest health government general health recommendations are that both men and women should limit their alcohol intake to 14 units per week in total, and try to allow 1-2 alcohol-free days per week. This equates to a total of 7 pints of 4% beer, or 7 shots of spirit, or seven 175ml glasses of 12% wine per week Use figure 3 to see how this stacks up in terms of your favourite drink(s).

- A slightly higher intake of 14- 21 units per week may provide some heart health benefits for older males who are fit, healthy and exercising regularly.

- These suggested limits are set for overall health in the general population – not for athletes in the run up to an important event. In the 3-4 days prior to an event, it’s much better to abstain from alcohol completely in order to ensure optimum hydration and to maximise your glycogen stores on the race start line.

- Try to allow as much time as possible to elapse between the finish of exercise and alcohol consumption and if possible, consume a recovery drink before you begin drinking alcohol.

- Stick to low-alcohol drinks (3% ABV or less – providing more fluid and less alcohol) if you can. If these are not available, improvise. For example, stronger beers and ciders (5-6%) can be diluted half and half with lemonade to make lager/cider shandies.

- Wine drinkers can achieve an equivalent ‘3%’ alcohol dilution by consuming mineral water between glasses of wine. As a rule of thumb, each glass of wine should be interspersed with 3 times the volume of water. For example, each 175ml glass of 12% wine should be drunk along with 525mls (around a pint) of water.

- Stick to the 0.5g per kilo of bodyweight rule of total alcohol intake; an 80kg athlete should consume no more than 5 units of alcohol in total while a 50kg athlete should stick to 3 units or less.

- Consuming salty snacks such as olives along with your alcohol, may help improve rehydration further.

See also:

Related Files

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.