You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Marathon race performance: lark or owl for the win?

SPB looks at intriguing new research on your day-night biological clock and marathon performance. Are natural early or late risers at an advantage, and what can all runners do to maximise marathon performance regardless of their daily body clock?

For maximum exercise performance, it stands to reason that all the physiological systems in the body must be working optimally and in harmony. However, there are many biological rhythms woven into human physiology that also play a role in determining performance. Some are quite short duration such as alertness and attention cycles, which repeat every hour or two, and some are much longer – for example the menstrual cycle in women, which repeats each month.

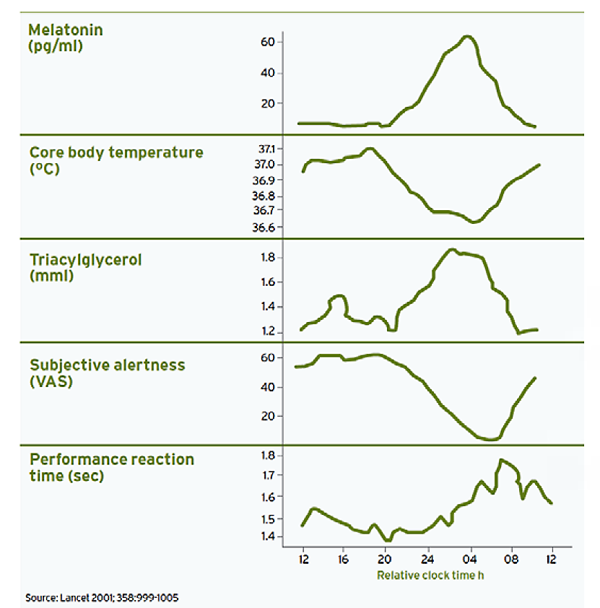

Of these, the daily night/day ‘circadian’ rhythm – governed by the light-dark cycle which occurs every 24 hours - is the most powerful rhythm affecting humans; as well as the sleep/waking cycle, it affects hormone secretions, body temperature, mental alertness and physical performance capacity through the day (see figure 1, which shows the typical daily variations of melatonin, secretion, core temperature, triacylglycerol, alertness and reaction time as a result of the circadian rhythm)(1).

Figure 1: Typical circadian rhythm-induced fluctuations in the body

The importance of the circadian rhythm

As mentioned above, of all the rhythms affecting the body, the daily circadian rhythm is most profound, and best researched in the context of sport performance. As a result of the rhythmic fluctuations induced by the circadian rhythm, many people experience maximum mental alertness, fastest reaction times and highest core temperatures in the late afternoon/early evening period. By contrast, the peak in melatonin (the body’s sleep hormone) concentrations in the middle of the night period leads to maximum fatigue/sleepiness and lowest alertness at that time.

The clear implication of these fluctuations for sportsmen and women is that concentration, skill learning, motor skill performance and muscular flexibility change throughout the day and this has indeed found to be the case(2). Evidence shows that these performance-related attributes tend, in most people, to peak in the late afternoon/early evening, in line with core temperatures(3-6).

Moreover, research also shows that circadian rhythm is not only synchronized to the 24-hour environment via the light-dark cycle but is also modified by behavioral cycles such as eating or drinking(7). This means that when the circadian rhythm is disturbed – for example by night shifts and time zone changes, the induced changes in eating habits/mealtimes can help perpetuate the disturbance, making it harder to restore the rhythm back to normal.

Circadian rhythm, sport and lark/owl tendencies

Every human is uniquely different so it’s no surprise to discover that each of us varies with respect to our circadian rhythm. In particular, humans differ in the timing of their circadian rhythms, with individuals falling along a circadian spectrum spanning ‘morningness’ to ‘eveningness’ extremes – more commonly known as ‘lark’ or ‘owl’ tendency(8).

You probably know of people described as ‘larks’; getting up early and feeling sharp and in good spirits first thing in the morning seems to come naturally to these people, while they tend to wind down in the evening and retire to bed fairly early too. ‘Owls’ on the other hand are night people, who often struggle to awaken, and then feel groggy and perform poorly for quite a while after waking. However their mood steadily rises through the day and by the evening they’re full of energy.

Physiologists believe that these differing characteristics are primarily related to core temperature patterns; table 1 below shows typical heart rate/core temperature trends for both types. However, pure lark or owl behavior represents the extremes and most of us lie somewhere in between. Moreover, research indicates that pure lark or owl characteristics may not be innate, but are likely to indicate circadian ‘dysrhythmia’ – a disruption to the normal circadian rhythm(9).

Extreme owl behavior arises from delayed sleep phase syndrome (where the circadian rhythm lags behind the 24-hour day), and extreme lark behavior from advanced sleep phase syndrome (circadian rhythm becomes advanced). The current suggestion is that while we may inherit a tendency to slip into lark or owl behavior, the correct circadian rhythm can be maintained with environmental clues, such as appropriate bright light exposure (more later)(10-11).

Table 1: Lark vs. owl characteristics

|

|

LARKS |

OWLS |

|

Peak resting heart rate |

Around 11am |

Around 6pm |

|

Lowest resting heart rate |

Around 3am |

Around 7pm |

|

Temperature lowest |

Around 3:30am |

Around 6am |

|

Temperature highest |

Around 3:30pm |

Around 8pm |

Circadian type and marathon race performance

Circadian preference is a term used to capture one’s subjective tendency towards a particular circadian type or tendency that often reflects a sleep–wake schedule. Research has shown that the timing of peak performance in athletes is dependent upon one’s natural circadian tendency(12). This means that pure larks tend to achieve their peak performance potential during the mid-afternoon period, while pure owls tend to peak during the mid evening period. Meanwhile, those who are not particularly lark or owl in their circadian tendencies tend to peak somewhere in between - ie late afternoon/early evening.

Given that marathons generally begin in early- to mid-morning, some researchers have wondered whether an individual’s circadian tendency may be a very significant factor in determining their race-day performance. Put simply, athletes with strong owl tendencies have a body clock that runs late compared to their lark contemporaries. This means they will physically peak late in the day, which would give them a distinct disadvantage in a morning marathon race compared to lark runners, who will be much closer to their peak performance window during morning/lunchtime hours. In short, while morning marathon starts may be great for larks, they may not be great for owls!

New research

To try and answer this question, a team of British researchers has carried out a retrospective analysis of marathon running performance in morning marathon races, and investigated whether/by how much a runner’s lark or owl tendencies impacts their race performance(13). Published in the Journal of Sleep Research, this study analyzed the circadian tendencies and race performances of 936 runners who competed in the 2016 London Marathon. During the pre-race registration process, the runners were asked if they would like to participate in a research study by providing feedback on a number of sleep lifestyle habits including caffeine use, alcohol intake, sleep habits (how many hours, bedtime and wake time, sleep onset times etc).

The initial research conducted with this collected data looked at marathon performance in relation to total sleeping hours, sleep onset and sleep efficiency. However, in this most recent study, which was published earlier this month, the researchers looked at the runners’ overall circadian patterns – specifically the degree of ‘morningness’ or ‘eveningness’ they rated themselves at – and something called ‘sleep inertia’. Sleep inertia is a term used to describe the period of physical, cognitive and psychological impairment that occurs immediately after awakening from sleep(14).

If you’re someone who awakes and can function at near full capacity after only a minute or two, you would be described as having low sleep inertia. On the other hand, if you need hour or more and at least a couple of cups of strong coffee to fully engage your brain, you have high sleep inertia! Although some of the sleep inertia experienced is situational (eg if you wake up and discover the house is on fire, you WILL feel awake immediately!), some is down to our individual physiological makeup – ie just a part of who we are(15). Given the relatively early start times of marathons, it stands to reason that runners with more prolonged and severe sleep inertia may be at a performance disadvantage. The researchers in this study hypothesized therefore that both greater degrees of eveningness and more sleep inertia severity would be associated with slower marathon completion times.

What they did

The first goal of the study was to use the information provided to assign the runners into categories for their lark or owl tendency. These were as follows (with number of runners in each category):

· Definitely a morning type (DM) - 316

· More a morning type than evening type (M > E) - 253

· More an evening type than a morning type (E > M) - 242

· Definitely an evening type (DE) - 125

The same categorization process was carried out for sleep inertia – ie how the runners typically felt upon waking (plus numbers in each):

· Very alert - 158

· Fairly alert - 344

· Slightly alert - 257

· Not at all alert - 77

Analyses examined the associations and interactions of circadian preference and sleep inertia with marathon completion times, with adjusted analyses accounting for age, sex and sleep health. These adjusted analyses were important to ensure that when lark and owl runners were analyzed for performance, only runners in the same age band, who were of the same sex and had similar overall patterns of sleep were compared – ie the only differing variable was circadian tendency.

What they found

The key findings that emerged from the analysis were as follows:

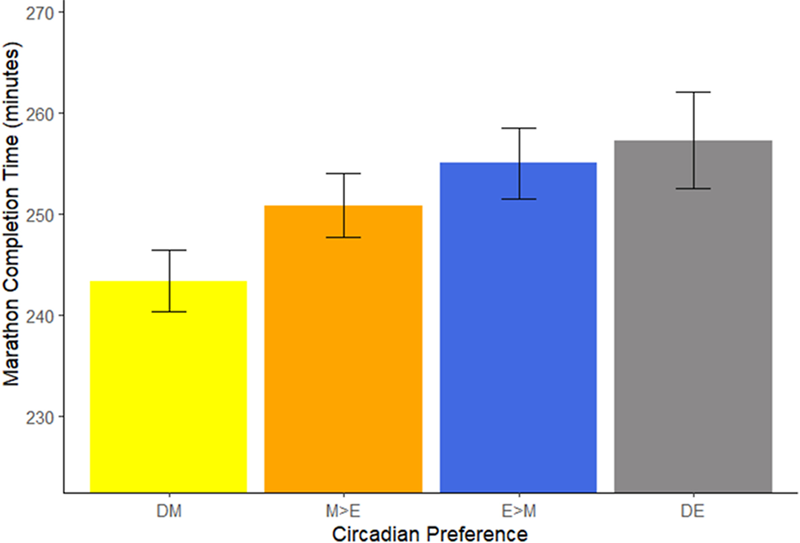

· There was a definite trend toward faster marathon times when runners were ‘definitely morning types’ (ie pure larks) and poorer results when the runners were ‘definitely evening types’ (ie pure owls) – see figure 2.

· When comparing pure larks to pure owls, this trend was very significant – ie being a pure lark was significantly associated with faster times than pure owls.

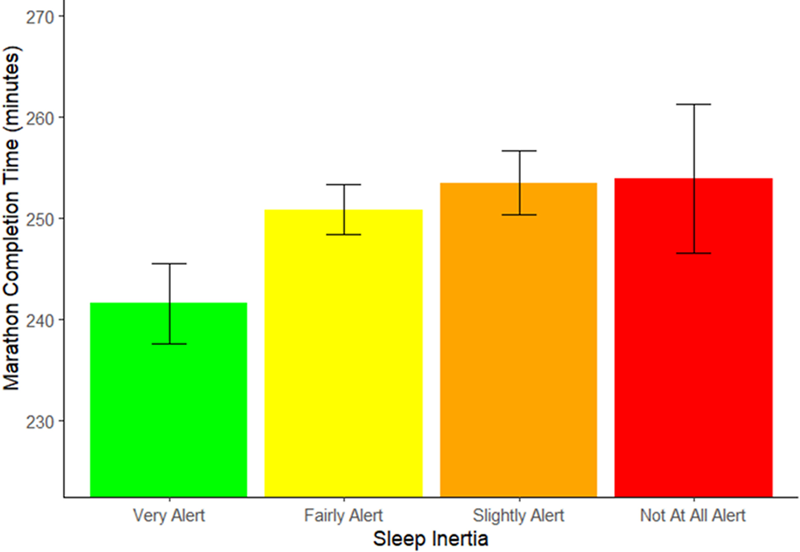

· Runners with high levels of sleep inertia tended to turn in slower times, with higher levels of inertia being associated with slower times (see figure 3).

· Oddly however, when sleep inertia levels were very high, the association of owlness or larkness to race times was weaker – ie circadian type seemed not to matter so much.

Overall however, the researchers concluded that runners with strong owl tendencies or higher levels of sleep inertia were negatively affected in terms of their marathon race times compared to runners without these tendencies.

Figure 2: Circadian tendency vs. marathon times

Average marathon completion time (minutes) plotted across the four levels of circadian preference: Definitely a morning type (DM); More a morning type than evening type (M > E); More an evening type than a morning type (E > M); and Definitely an evening type (DE). ‘Definitely morning’ types significantly outperformed both ‘definitely evening’ and ‘more evening than morning’ types.

Figure 3: Sleep inertia vs. marathon times

Average marathon completion time (minutes) plotted across the four categories of sleep inertia. High levels of sleep inertia predicted slower marathon times compared to the ‘very alert upon waking’ category. Bizarrely however, when sleep inertia was very high (not at all alert), this tendency was less significant.

Practical implications

This study provides clear evidence that runners who are much more owl like appear to face a distinct disadvantage when competing in morning marathons compared to their lark like counterparts. However, this disadvantage may not be purely down to inherent circadian tendencies. In their summary, the authors pointed out that other factors and training dynamics were likely relevant to understanding the potentially deleterious effects of eveningness. For example, they found that greater eveningness was associated with increased weekly alcohol use, and a greater frequency of electronic device use within one hour of bedtime. These are both behavioural patterns that are unlikely to aid training, recovery and race-day performance. If you’re an owl and struggle to get into a good bedtime routine therefore, getting the sleep basics right is a good place to start – see this excellent article by James Marshall for practical recommendations.

But what about athletes who have good bedtime routines but simply struggle with their body clock and a strong owl-like tendency? One option is to use techniques borrowed from time zone adjustments to overcome jetlag in order to try and nudge your body clock into more of a lark-like (or at least neutral) state in the run up to a marathon. Simple steps that can help shift the body clock forward include the following:

· Over a period of time, set your alarm for an earlier time than usual (in 15-minute steps) and then when you get up, ensure that you are exposed to bright white light. During mid-summer, this is easily achieved by simply going outside soon after rising. At other times of the year however, you will need to use a portable light device (often recommended for bright light therapy) containing the all-important blue wavelengths that are known to stimulate a shift in the body clock when used early in the morning(16).

· By the same token, don’t expose yourself to bright light containing blue wavelengths (emitted by most electronic devices with screens) after 8pm.

· Don’t perform evening training sessions, which tend to shift the body clock backwards (ie make your circadian rhythm even more owl-like!). Where you can, try and train in the morning.

· If you know the time of your race start, try and time as many of your training sessions similarly in the two months beforehand so that your body is more physiologically prepared for exercise at that particular time of day.

References

1. J Cell Physiol 2022. 237(8), 3239–3256 Lancet 2001. 358: 999-1005

2. Heliyon 2023. 9(9), e19636

3. Int J Sports Med. 1997 Oct;18(7):538-42

4. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2004 Jun;92(1-2):69-74

5. Can J Sport Sci. 1992 Dec;17(4):316-9

6. Int J Sports Med. 2004 Jan;25(1):14-9

7. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2018; 4 (1), e000443

8. Chronobiology International 2017, 34(3), 426–437

9. American Sleep Disorders Association. International Classification of Sleep Disorders, revised: Diagnostic and Coding Manual. Rochester, Minn. 1997

10. EMBO Rep. 2005; October; 6(10): 930–935

11. Sleep1990; 13:354-361

12. Current Biology 2015. 25(4), 518–522

13. J Sleep Res. 2024 Oct 19:e14375. doi: 10.1111/jsr.14375. Online ahead of print.

14. Nature and Science of Sleep, 11, 155–165

15. SLEEP Advances, 4(1), zpac043 doi.org/10.1093/sleepadvances/zpac0

16. Biol Psychiatry. 2006 Mar 15;59(6):502-7

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.