You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Post-exercise recovery: it’s all in the mind!

Andrew Sheaff investigates new research suggesting that post-exercise recovery can be profoundly affected by how you occupy your mind following training

When it comes to maximizing recovery, the focus has always been on finding and implementing more effective training interventions. Most athletes and coaches want to know the most effective training strategies, they want to know the best way to implement these strategies, and they want to know how to organize different training activities into weekly, monthly, and even yearly training plans.

However, training is only one half of the improvement process. To make progress, athletes need to train hard and then recover from that training in order to gain the adaptations they are seeking. In recent years, more and more attention has been given the recovery side of the improvement equation. That makes sense because at some point, athletes can’t train harder, longer, or better, so they need to find ways to recover more effectively.

Intelligent recovery

The most powerful strategy for facilitating effective recovery is the development of intelligent training plans. Rather than training at maximal intensity and maximal volume every single day, effective training plans alternate between training days of higher and lower stress, a concept often extended to implementing weeks or even months of higher and lower training stress. For many, there are even different times of year where training stress is elevated relative to others. The baseline for effective recovery therefore is sound training.

Beyond the focus on building more recovery into training plans, many coaches and athletes aim to further accelerate recovery in order to enhance the adaptation athletes experience, allowing them to train harder, sooner. To do so, they often rely on external interventions where a physical stimulus is presented to the body, such as ice baths, massage, or foam rolling.

Internal recovery

While these external recovery interventions can be effective, they largely ignore the internal state of stress within the body, which strongly governs recovery. During intense physical activity, the sympathetic nervous system provides the hormonal environment to allow for large physiological outputs. When it’s time to train and compete, this is the state you want your body to be in.

However, this is not a physiological state conducive to recovery. By contrast, the parasympathetic nervous system is responsible for promoting a psychological state that allows for the body to rest and repair itself. This is a calmer state where recovery rather than performance is emphasized. It follows therefore that after training, if an athlete is unable to reduce the input of the sympathetic nervous system, and increase the activation of the parasympathetic nervous system, they’ll struggle to recover.

Mindfulness and recovery

In recent years, there’s been a growing interest in mindfulness activities because of their ability to reduce stress, perhaps by influencing the nervous system to tone down the sympathetic input and increase the parasympathetic input. While these interventions have generally been applied outside of the context of sport, researchers believe it’s possible that mindfulness interventions may help athletes shift their physiological state toward one associated with better recovery.

In particular, as training sessions result in intense physiological activation, it’s possible that performing a simple mindfulness routine following training may help athletes shift from a sympathetic state to a parasympathetic state more quickly and more completely. If so, that could kick start the recovery process from an internal perspective rather than an external perspective. But does this approach work? Fortunately, a research group from the United States has carried out new research to try and answer this exact question.

The research

The researchers recruited 38 Division-1 collegiate American football players(1). For those unfamiliar with the American collegiate athletic system, Division-I represents the highest level of collegiate sports, where the majority of future professionals compete. The goal was to determine if the activities conducted following training can influence the recovery process after training.

For the study, the athletes performed three training sessions, each separated by one week, with each session occurring on a Monday for consistency. The training sessions were extensive and intensive, last approximately 2.5 hours each. These sessions included a full spectrum of activities, including sprint intervals, aerobic training, agility training, as well as strength and power training. These training sessions were the same for all subjects across all three weeks. After each session, the subjects in engaged in one of three different relaxation interventions (ie over the three weeks, all the athletes performed all the recovery interventions):

· Mindfulness - the mindfulness group was instructed to lie on the floor in a dark room. Guided by trained mindfulness professional, they performed breathing techniques and body scans.

· Rest – in the rest intervention, the subjects were asked to remain seated in a room and in perform restful activities such as refuel or talk with teammates.

· No intervention (control) - the no-intervention group was assigned to perform their typical post-training activities. They were free to do whatever they pleased based upon their normal routine.

To assess the physiological impact of the different interventions, heart rate, respiratory rate, and heart rate variability were measured immediately following training. These measures all indicate the level of physical activation the athletes are experiencing, particularly heart rate variability (see this article), which provides insight into the relative balance of parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous system activation. These measures were then repeated 15 minute later to assess the degree of physiological change the subjects experienced.

What they found

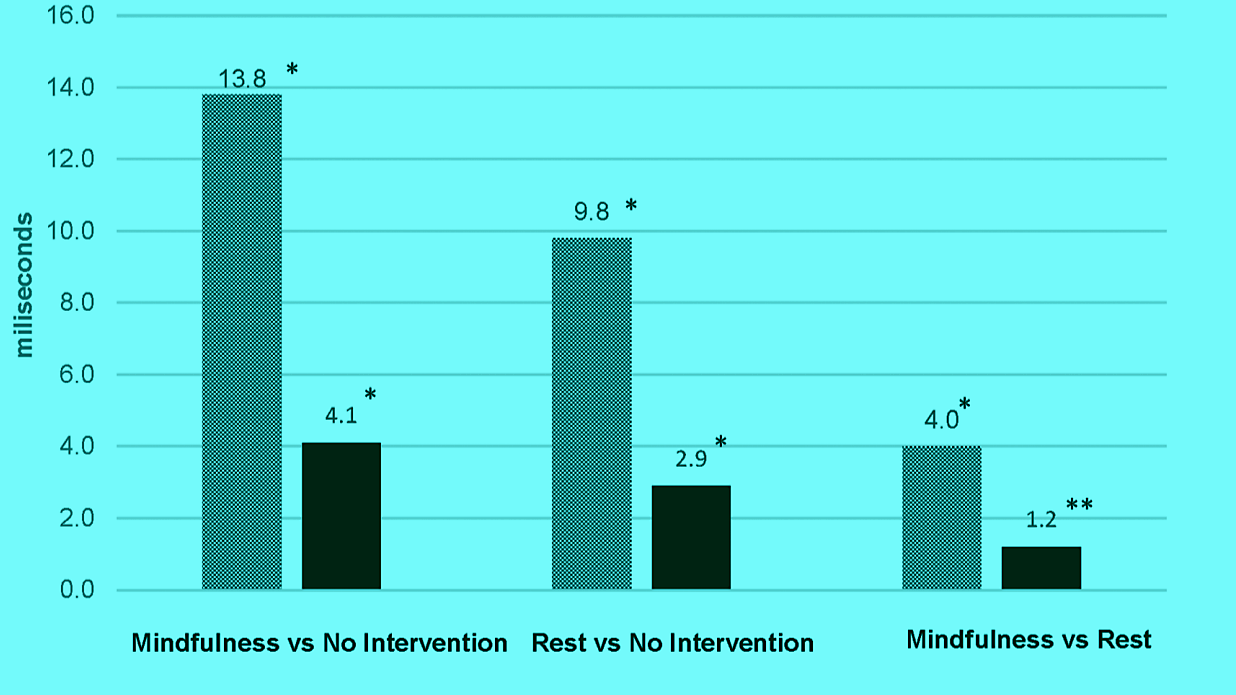

Unsurprisingly, each intervention resulted in significantly lower heart rates and respiratory rates after 15 minutes, as well as improved heart rate variability measurements (see figure 1). These findings are completely unsurprising considering that the subjects were no longer exercising at high intensity and had moved to a relative state of rest. What was particularly interesting however was the degree to which these measurements changed between the different interventions.

While all heart rate measurements improved, the difference between the mindfulness group and no interventions was twofold, with the heart rate dropping by around 80 beats per minute and 40 beats per minute, respectively. The rest group experienced a decrease of approximately 66 beats per minute, about halfway between the other groups. There were statistically significant differences between the mindfulness and rest group, the mindfulness and no intervention group, and the rest group and no intervention group.

The same results were found when it came to respiration rates. Respiration rates dropped much lower in the mindfulness group relative to the other two groups - results which were statistically significant (ie a real effect observed and not just a statistical blip). Although not as large as the differences between the mindfulness group and the no intervention, there were also significant differences between the rest group and the no intervention group.

Unsurprisingly, the same dynamic occurred with both measures of heart rate variability (figure 1). The mindfulness intervention proved superior to both the rest and the no intervention group. Yet again, the rest group still proved superior to the no intervention group. These differences were all statistically significant. This indicated that the mindfulness group experienced a more profound shift toward parasympathetic nervous system activation.

Figure 1: Differences in heart rate variability following different post-exercise recoveries

Overall, these results suggest that either mindfulness activities, or even just taking to time to rest passively, can help shift the body towards a physiological state associated with recovery. In particular however, mindfulness activities may be particularly powerful. If recovery is a primary goal following training - and it should be – this research indicates that simple activities can shift athletes from a physiologically activated state necessary for performance, to a more relaxed state necessary for recovery.

Practical applications for athletes

Most of us are busy. We might be moving right from our training session to the next part of the day, whether that be engaging in work, with family, or anything else that demands our time and attention. Unfortunately, that may lead us to carry the physical stress we experience during training right into our next activity, thereby prolonging or even preventing a return to a more relaxed physiological state. Doing so doesn’t feel great, and it can certainly have a long-term impact on recovery.

However, by performing simple mindfulness activities, or even spending some time resting passively, you can kick start your recovery. You don’t need to be an expert in mindfulness to gain benefits; simple breathing exercises such as counting your breaths are a large part of mindfulness practice and can be effectively implemented by anyone regardless of their level of mindfulness training.

While external recovery strategies certainly have their place, focusing on getting internal recovery right is always a winning proposition. If you’re in a time crunch, you may not be able to take the full fifteen minutes used in this study. However, it’s likely that shorter interventions will also yield a positive impact, and anything that can help you slow down after training is going to be beneficial.

When it comes to applying these findings, stick with the main concept and find a way to make it work for you. More than anything else, you need to help your body to ‘slow’ down. Something as simple as patient, deep breathing in in a chair or even the shower can make all the difference. The key idea is to focus on relaxing, slowing your breathing down, and slowing your heart rate down. Use the concept and find a way to make it practical in your life. By taking a small amount of time after training to accelerate your body’s transition from a stress to a relaxed state, you’re much more likely to recover faster and feel better as a result – what’s not to like!

References

1. Front Sports Act Living. 2023 Nov 28:5:1267631. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2023.1267631. eCollection 2023

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.