You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Sprint intervals: the verdict of the court

Could sprint intervals be the perfect fitness tool for racquet sport players? SPB looks at some brand new research

In recent years, a growing body of evidence has accumulated showing that performing regular bouts of high-intensity interval training is an extremely effective training tool for athletes seeking to maximize performance for a relatively low training workload(1). Put simply, short sessions of high-intensity intervals are a great way of producing gains in aerobic power, enabling an athlete to sustain a higher intensity/pace/workload for longer before fatigue sets in. And as we’ve discussed in previous SPB articles, high-intensity intervals are also a very time-efficient for the fitness gains achieved, easy to add to an endurance program, and psychologically less demanding to carry out – all of which explain why they have become so popular among athletes seeking to push their fitness to higher levels.

The rise and rise of sprint intervals

One of the key findings in the research on high-intensity interval training in recent years is that very short, very high intensity intervals of under 15 seconds’ duration can also be extremely effective for building fitness. For example, a Canadian study found that a HIIT program consisting of sessions consisting of six intervals of just 10 seconds sprinting produced significant gains in measures of aerobic fitness(2)! Other examples include research that found reducing interval lengths from 30 to 15 seconds produced the same magnitude of fitness as the original 30-second interval program(3), and research on soccer players, which found that performing sessions of 15-second intervals was more effective than their normal soccer fitness program, with faster results!

Sprint intervals for sprint-sport athletes

As well as being a powerful and time-efficient tool for sharpening aerobic fitness, sprint interval training has also gained scientific attention for its ability to produce rapid improvements in anaerobic capacity and associated metabolic adaptations(4). Because it challenges athletes to perform at or near maximal effort, sprint interval training promotes gains in power and speed, which are extremely important qualities for many athletes in a range of sports.

This gives sprint interval training a distinct advantage over steady-state endurance exercise, especially in sports such as soccer, tennis, basketball etc, which require intermittent but repeated bursts of speed and power. Indeed, research shows that by mimicking the physiological demands of these intermittent sports, sprint interval training can help athletes better prepare for the rigors of competition(5). And as mentioned above, the time efficiency of sprint interval sessions make them appealing for amateur athletes with busy schedules such as work and family demands to accommodate(6).

Sprint intervals for racquet sports

Racquet sports such as tennis and squash are characterized by a series of intense, short-duration efforts that demand rapid bursts of power, agility, and speed. These efforts include explosive serves, quick sprints to reach the ball, and forceful groundstrokes, all of which heavily rely on the anaerobic energy pathways(7). The anaerobic/lactate system becomes dominant during extended rallies and intense baseline exchanges, where energy is required at a higher rate than can be delivered by the oxygen-dependent aerobic system(8). This of course leads to the accumulation of lactate and muscular fatigue.

It follows therefore that a well-developed anaerobic energy system not only enables racquet players to execute powerful strokes and swift movements but also helps in delaying the onset of fatigue and sustaining peak performance during crucial match moments. That’s important because studies show that improving anaerobic capacity can lead to enhanced sprinting abilities, quicker court coverage, and better overall match performance(9).

Given that a racquet sport player’s success hinges on the efficient utilization of the anaerobic energy system, and given that sprint interval training is highly effective at training that system (as well as giving gains in aerobic fitness), the obvious question is how effective can sprint interval training be for racquet sport players? It turns out that there’s actually very little research on this topic. Most of the existing studies on sprint interval training have primarily focused on cardiovascular benefits and metabolic changes among general or obese populations(10). And those carried out on athletes have studied team sports such as soccer, basketball, volleyball, and field hockey(11-13). Furthermore, most of these studies have been conducted in laboratory settings rather than in the settings where athletes actually practice their sport. Overall therefore it hasn’t been possible to answer this question.

Brand new research

The good news however is that brand new research on the use of sprint interval training for performance enhancement in tennis players has just been carried out. Published in the journal ‘Scientific Reports’, this study was carried by a team of Chinese researchers who investigated the impact of low-volume, court-based sprint interval training on the anaerobic capacity and sport-specific performance in competitive tennis players(14).

Twenty-four male competitive collegiate tennis players participated in the study, which lasted for six weeks. These players were on average training for around 20 hours per week, which consisted of three hours of technical and tactical tennis practice per day and one hour of physical conditioning per day based on traditional endurance sessions performed five times per week. Following recruitment, the players were then randomized to one of two groups:

· Sprint interval training – three sprint interval sessions per week with training taking place on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays.

· Traditional endurance training - 45 minutes of continuous treadmill running at a velocity corresponding to 75% VO2max (moderately hard) three times per week on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays.

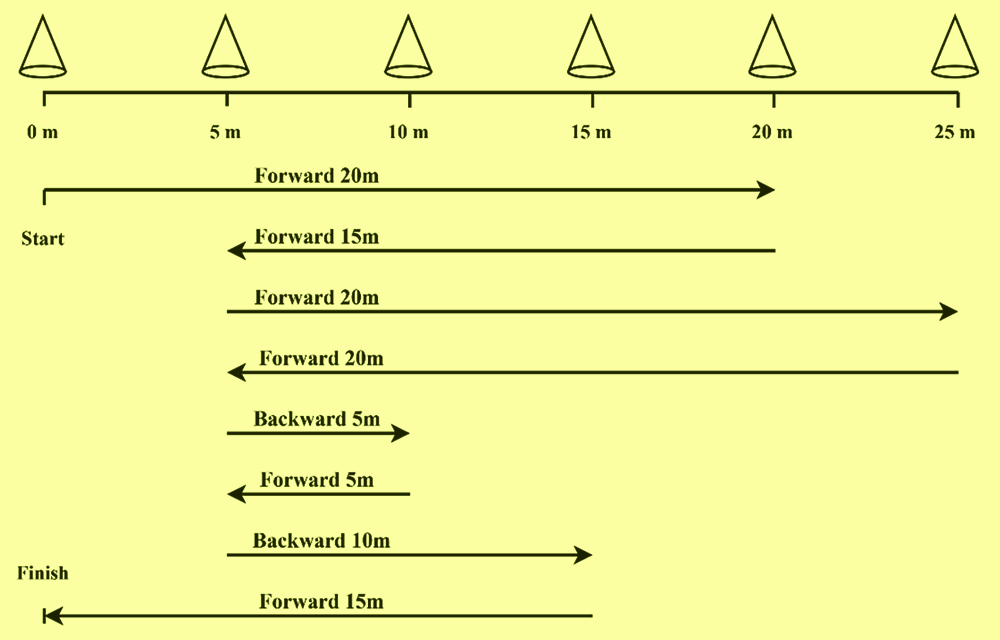

The sprint training protocol involved three sets of high-intensity sprints interspersed with short recovery periods, performed on the tennis court. Each interval run was 110 m in total distance and involved forward and backward sprints over distances ranging from 5-20 metres with multiple changes of direction (see figure 1). Each set comprised three repetitions of a 110-m sprint with a 20-second recovery period between each sprint, followed by a 5-minute recovery period between sets. For all training and testing sessions, regardless of group, the participants followed a 10-minute standardized general warm-up and 10-minute cool-down protocol including jogging, skipping, dynamic warm-up, and stretching.

Figure 1: The sprint training protocol

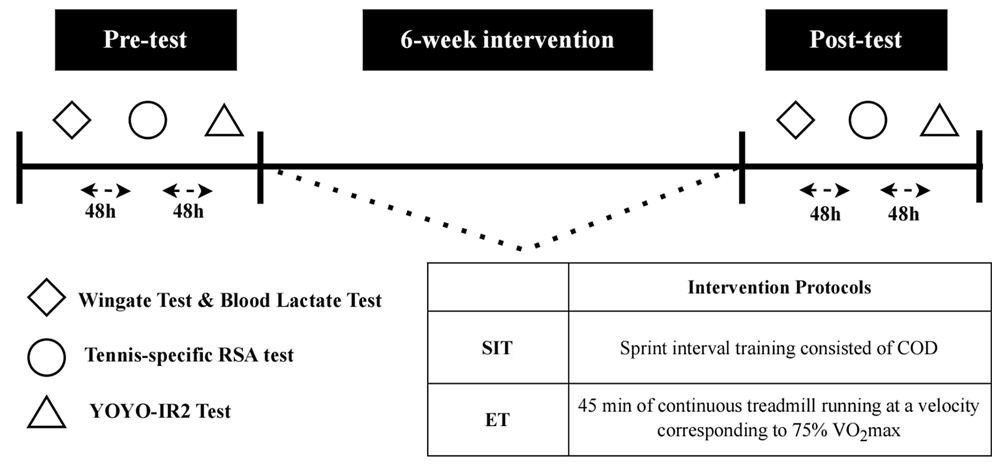

Before and after the 6-week training block, all the tennis players also underwent testing to assess key parameters of tennis performance. These assessments included:

· The Wingate Anaerobic Test (a graded test to exhaustion, which measures peak anaerobic power and anaerobic capacity).

· The elimination rate of blood lactate (how quickly the players were able to clear blood lactate and physiologically recover).

· Tennis-specific repeated sprint ability.

· The Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test Level 2 (a test that measures high-intensity aerobic capacity).

The overall study protocol can be seen in figure 2. Finally, the researchers compared results from the two groups.

Figure 2: Study design protocol – sprint intervals vs. traditional endurance training

What did they find?

The key finding was that the sprint interval training protocol utilizing a court-based, two-directional sprinting protocol, led to comparable improvements in anaerobic capacity and better tennis-specific repeated sprint performance on the court compared to the conventional endurance training on a treadmill. Specifically, the sprint interval training produced:

· A superior improvement in the Wingate ergometer test (ie greater average power).

· Better tennis-specific anaerobic performance in the repeated sprint test.

· A trend towards larger improvement in aerobic and anaerobic running performance (ie better scores in the YoYo-IR2 distance test).

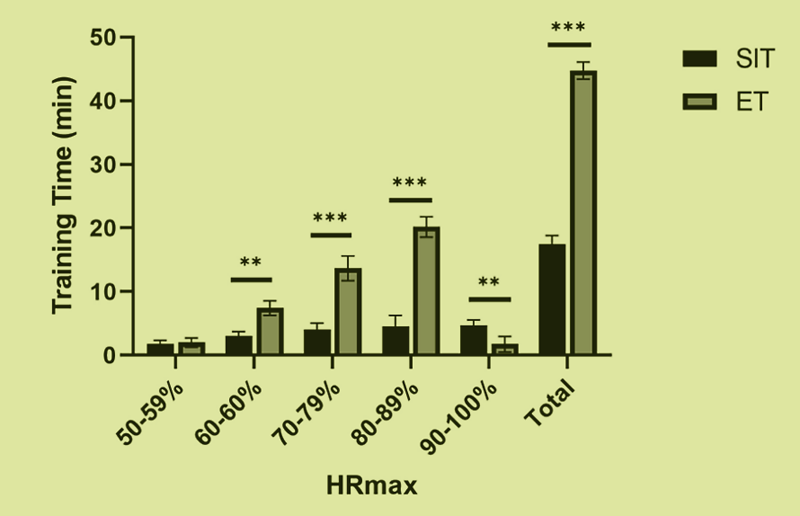

Importantly (and incredibly), these benefits were obtained in a much shorter time frame; in the sprint interval-trained players, total exercise time was 90% less than the treadmill endurance training and even when the rest periods were added in, the sprint intervals still only required a third of the time to complete compared to the endurance training (see figure 3)! And on a practical point, these results were achieved without the need for specialized equipment such as treadmills or bikes.

Figure 3: Minutes per session and total minutes accumulated in each protocol

Practical advice for athletes

These results are both impressive and persuasive for tennis and other racquet sport players who want great training outcomes with reduced time commitment. But how was it possible that the traditional endurance training group didn’t perform as well despite perform three times the training volume and accumulating much more time with their heart rates in the range of 50-90% of maximum? The likely answer is the time spent at 90-100% HRmax. Research shows that accumulating as much time as possible approaching or at VO2max (90-100% HRmax) is known to be important for producing both aerobic and anaerobic performance gains(15-17). Now compare the accumulated times by heart rate in figure 3 and you will see that compared to the endurance trained players, the sprint interval trained players accumulated 3-4 x as much time in this all-important zone!

In summary, this study suggests that low-volume sprint intervals sessions performed on the court are excellent for improving anaerobic capacity and sport-specific performance in competitive tennis players (or any other racquet sport player) - without the need for specialized equipment. Even better, the reduced time spent and relatively low total training load means that you can be fresher for practicing and improving your sport-specific skills and tactics by playing tennis/squash/badminton etc instead of performing long, drawn-out endurance sessions. And the icing on the cake is that with less time spent on non-specific fitness training, you’ll have more time to do this!

References

1. Sports. 2015 Oct;45(10):1469-81

2. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010 Sep;110(1):153-60

3. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2014 Nov;114(11):2427-36

4. Open Access J Sports Med. 2014 Oct 17;5:243-8

5. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2008 36, 58–63

6. Sports Med. 2013. 43, 313–338

7. J. Physiol 2008. 586, 151–160

8. Sports Med 2007. 37, 189–198

9. Br. J. Sports Med 2014. 48(Suppl 1), i22–i31

10. Br. J. Sports Med 2007. 41, 711–716

11. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 2011 1554–1560

12. Sports Med 2013. 43, 927–954

13. J. Strength Cond. Res 2018. 32, 3051–3058

14. J. Strength Cond. Res 2018. 32, 617–623

15. Scientific Reports 2024. vol14, article number: 19131

16. Eur J Appl Physiol. Jul 2019;119(7):1513-1523

17. Physiol Behav. May 15 2018;189:10-15

18. Eur J Appl Physiol. Feb 2012;112(2):767-79

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.