You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Strength for athletes: maximize the bang, limit your buck!

SPB looks at new research on how to maximize the gains from a strength session while keeping your effort levels under control

Here at SPB, we’ve explored the benefits of strength training for athletes in great depth over recent years – and for good reason. That’s because, a very large body of research has accumulated showing that strength training can improve performance in a wide range of athletes. It’s not just that the increased resilience of stronger muscles can help reduce the risk of injury – both those arising from inherent weaknesses and those of strength imbalances between different muscle groups(1,2). And it’s not only about the gains in strength and power(3), which can help athletes in sports where strength, power, speed, force and acceleration are important.

Less appreciated

What’s less appreciated is that strength training can also seriously benefit endurance athletes by increasing muscle efficiency, which means that muscles require less oxygen to sustain a sub-maximal pace, resulting in less fatigue(4-8). This increase in muscle efficiency is more technically known as ‘muscle economy’ – important since research shows that high levels of muscle economy are strongly linked to endurance performance(9,10). Indeed, research shows that for events of over 20 minutes’ duration just two factors – maximum aerobic capacity (VO2max) and running economy - can account for 92% of the variance in endurance performance(11).

Getting strength-training ‘bang for buck’

Given that adding strength training sessions to an athlete’s program will almost certainly produce performance gains, the question is how best to structure those sessions. Strength training requires mental and physical energy, but so do the athlete’s sport-specific training sessions. There’s only so much energy an athlete has before risking excessive fatigue, which means that any strength training needs to be as productive as possible so the benefits can be had while minimizing demands on the athlete’s physical reserves. In plain English, athletes need biggest bang per unit of time and effort invested!

There are many, many permutations of strength training programs, all of which can impact the energy and effort required and the benefits gained. Among the factors that can be manipulated are:

· Choice of strength exercises.

· Order of strength exercises.

· Number of sets of each exercise.

· Resistance or weight used in each exercise.

· Number of reps in each exercise set.

· Optimal rep speed.

· The rest length between sets.

· The frequency of strength sessions and how they are sequenced into an overall training program.

In previous SPB articles, we have looked at what the recent research says about how these factors can be manipulated for superior gains, including exercise order, how to combine strength training into a mixed session, how many reps/how hard to push in each set, optimal rep speed, rest length between sets, training frequency, and many others. Of these, how hard to push during each set is one of the most critical factors because it plays a major role in determining the size of the stimulus generated, but also the level of fatigue experienced.

How close to failure?

In order to create a strength/muscle growth stimulus in a training session, muscles need to experience a degree of overload in that session. This overload involves pushing the muscle fibers to do more than they are accustomed to. It follows that when performing a strength exercise to induce overload, it is necessary to approach or reach the point where the muscle fibers cannot do what is being demanded of them – the so-called ‘failure point’. But how close to failure should you be working to achieve maximum results?

While it has been traditional among strength athletes and bodybuilders to work right up to failure in order to promote maximum strength and muscle growth, more recent research suggests that actually, there are no additional gains working to failure compared to quitting a couple of reps before failure(12). However, other studies have found that when the loading is light (below 50% of 1-rep max), working to failure does generate better strength and muscle growth gains(13). Yet more research found that rather than working to failure or not, what really seems to make the difference is the total volume of high-quality, high-load reps accrued in a strength session(14).

With the uncertainty in these findings, you might be thinking that in order to be on the safe side and ensure maximum gains from a strength session, you should just go ahead and work to failure anyway. However, working to failure comes at a price – a price that may work against the athlete:

· Performing sets to momentary muscular failure can incur very high levels of neuromuscular fatigue that impairs the quality of the movement during the later reps, the ability to perform additional sets and therefore, a reduced overall training stimulus in a strength session(15).

· Some research suggests that the extra muscle damage caused by working to failure compromises protein synthesis directed towards muscle hypertrophy. In short, the extra protein synthesis that would have been directed to muscle growth after a strength workout is instead directed to repair of damaged muscle fibers(16).

· Athletes who do not regularly work to failure can experience a large amount of delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS), which may impair their ability to train for quite a number of days afterwards!

Uncertainties

Some research has reported that as you steadily accumulate more and more reps in a set, the strength gains from that set steadily increase, but once you get within 2-3 reps of failure, there are no more gains to be had(17). But this is complicated by the fact that in many studies in strength training almost to failure (ie leaving two or three reps in reserve), estimations of the reps in reserve (ie when to terminate the set) have been very variable and uncertain - especially where the participants are less experienced strength trainers, and also down to the fact that individuality also seems to play a large part in determining just how much is left in the bank for the end of the set(18).

Looking at the scientific data as a whole on this topic, we can conclude that while working to momentary muscular failure is undoubtedly effective for promoting muscle growth, reaching close proximities to failure may also be sufficient, even in experienced resistance-trained individuals. If the latter is the case, this is a win-win strategy as it would mean that maximum gains can be achieved without the drawbacks of working to failure.

The problem however is that it’s difficult to make firm recommendations for trained athletes on whether they should work to failure or keep some reps in reserve as only one study has ever been conducted on this topic where the participants were resistance trained(19). While this found that training near to failure was as effective in promoting muscle growth as training to actual failure, it studied only a small number of participants who trained using just one exercise, and where there was no ‘reps in reserve’ strategy – ie the participants terminated the set randomly when they felt tired, rather than keeping to a reps in reserve goal (eg terminating the set once they knew they had only two possible reps left in the tank).

New research

To try and reach some definitive conclusions on whether trained athletes can make maximum gains without working to failure (ie by using a reps in reserve technique), a team of Aussie scientists has just published a brand new study comparing the two approaches(20). Published in the Journal of Sport Sciences, this study investigated 12 male and six female resistance-trained athletes with an average of 7+ years’ strength training experience. These athletes trained twice per week for eight weeks on the leg press machine (Hammer Strength 45-degree machine) and the leg extension machine, with the goal of building quadriceps (frontal thigh) size and strength.

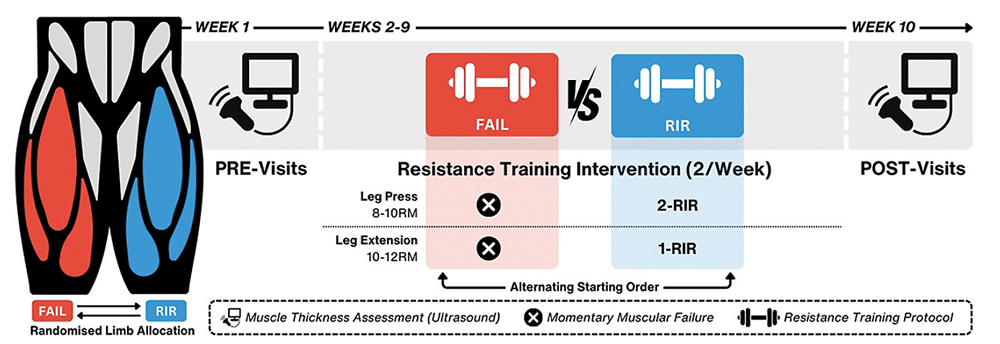

Participants performed both exercises on both legs twice per week. However, the study design was unusual (and clever) in that for each participant, the left and right legs were randomly allocated to perform single-leg press and single-leg leg extension exercises either to:

· Momentary muscular failure

· Perceived 3 reps in reserve for leg presses, and perceived 1 rep in reserve for the leg extension.

In other words, each participant trained one leg to failure using both exercises and trained the other leg using reps in reserve using both exercises (see figure 1 for the study design). Before and then again after the intervention, muscle thickness measures of two quadriceps muscles (rectus femoris muscle [RF] and vastus lateralis muscle [VL]) from both legs (ie the failure-trained leg and the rep in reserve-trained leg) were taken using ultrasonography. Since gains in muscle thickness directly correlate to muscle mass gains, this served as a good measure of the effectiveness of each training approach for building muscle mass and strength. As well as changes in lifting speed to determine progressive fatigue, the researchers also assessed the total reps/volume/load performed in each condition to see how much more total training load (if any) occurred with the training to failure approach.

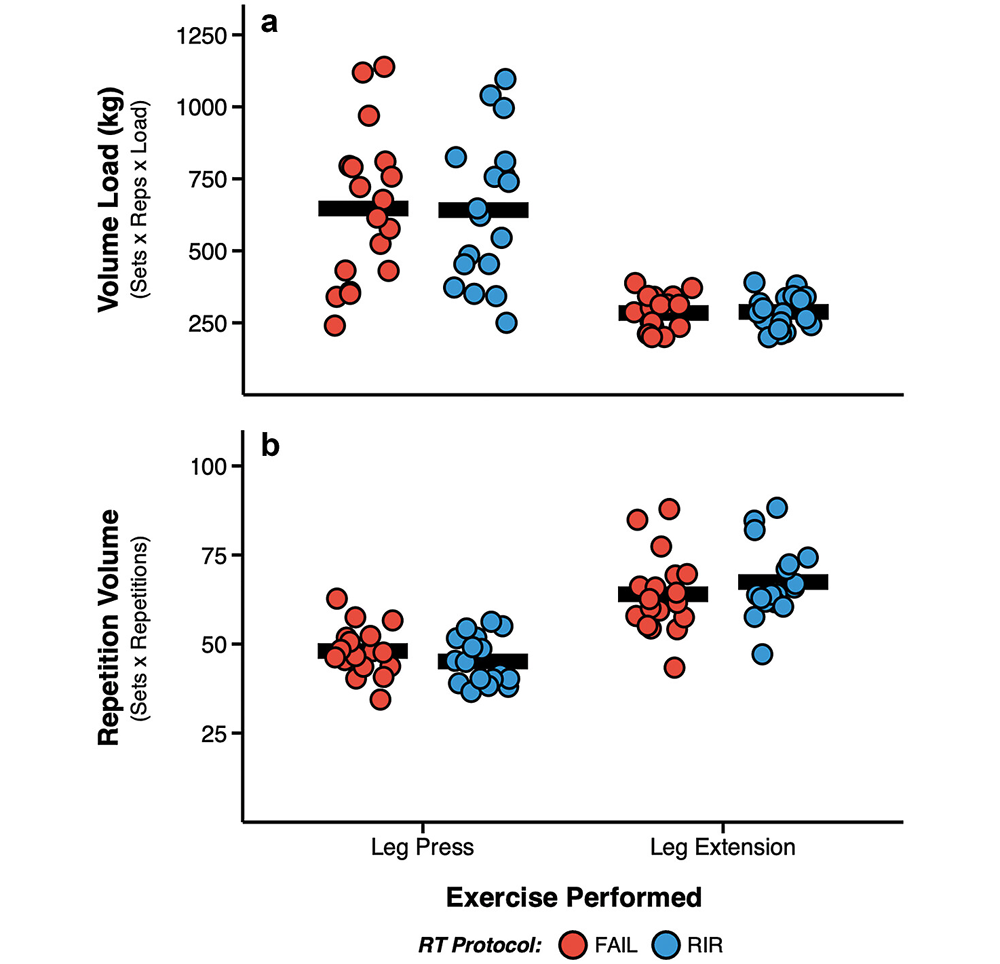

Figures 1&2: Study design protocol (top) and comparison of reps and loading in each design (bottom)

Figure 1 (top): Participants completed two pre-testing ultrasound assessments to measure muscle size, and a repetitions-to-failure and repetition-maximum load assessment. They then completed 16 experimental sessions across the 8-week intervention (two times per week). After the intervention, two more ultrasound assessments were carried out to measure gains in muscle mass. NB: RIR = repetitions-in-reserve; RM = repetition-maximum.

Figure 2 (bottom): Each dot represents an individual participant. Thick black line = average for all the participants. Red = to failure; blue = reps in reserve. There was no significant difference between protocols in the total reps or total loading.

What they found

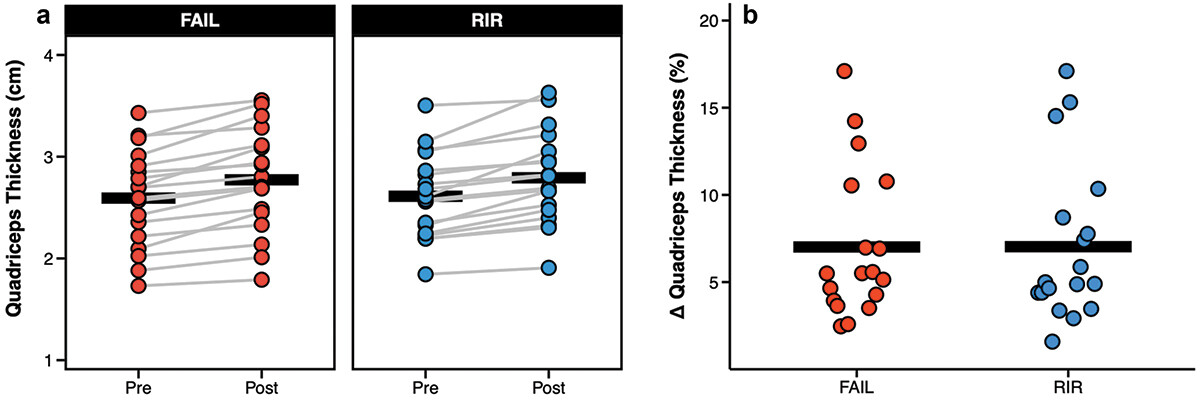

There were a number of interesting findings. Firstly, it was apparent that the total reps accumulated and work done was very similar regardless of whether a ‘reps in reserve’ a failure protocol was being followed (see figure 2). Secondly, it was clear that (as might be expected) the failure protocol resulted in a much great decline in rep velocity as the set progressed, which in turn indicates much higher levels of neuromuscular fatigue in each set. The most important question of course was whether a ‘reps in reserve’ protocol was able to produce the same gains in muscle thickness/mass as the failure protocol? The answer was an unequivocal ‘yes’. As figure 3 shows, both protocols resulted in the same gains in muscle thickness and changes in muscle thickness when comparing pre-8 weeks to post-8 weeks.

Figure 3: Comparison of muscle thicknesses and thickness changes

Each dot represents an individual participant. Thick black line = average for all the participants. Red = to failure; blue = reps in reserve. Raw thickness data is shown for rectus femoris and vastus lateralis muscles. There was no significant difference between protocols, either in absolute thickness or % change in thicknesses.

Practical recommendations for athletes

This latest study is important because it tells us that even when athletes are highly experienced at strength training, working to failure does NOT confer extra gains. This is at odds with much of the traditional thinking, which has argued that because well-trained individuals (eg athletes and bodybuilders) are able to tolerate much greater training stresses than most people, pushing on to failure in a set might provide an extra stimulus to increase muscle mass and strength(21,22).

If training to failure does create extra stimulus at the end of a set, why doesn’t it seem to produce any extra strength or muscle mass gains? One reason (mentioned earlier) is that the extra damage to muscle fibers caused by failure training means more muscle repair is needed, which directs some of the body’s resources away from muscle growth. However (and probably more importantly), while training to failure allows more reps and loading in the first set, the extra neuromuscular fatigue generated decreases the energy available to maintain reps and total loading in later sets, drastically reducing rep numbers. The net result is that over the course of three sets for a muscle group, total loading and reps is no higher in a failure protocol compared to holding back 1-3 reps in reserve.

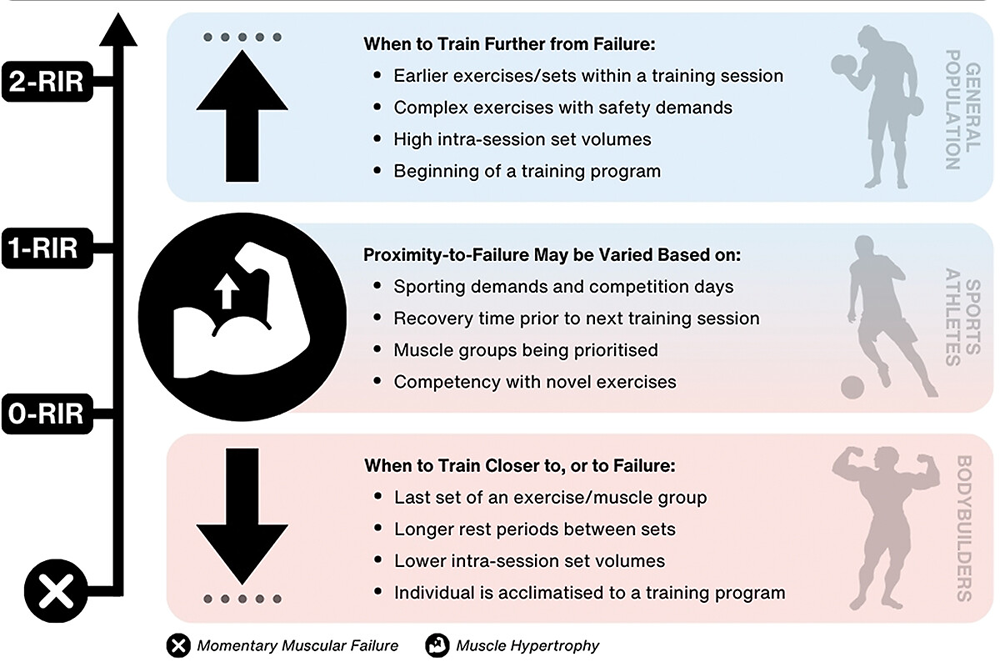

If you’re an experienced strength athlete or have an extensive strength-training background, should you train to failure? The balance of evidence seems to suggest that you shouldn’t. Not only does the evidence suggest that there are no significant performance adaptations to be had, training to failure produces more fatigue and requires more neuromuscular resources – resources that are best reserved for your sport specific training. That said, it is important to understand that not training to failure doesn’t mean stopping as soon as you feel like you’re exerting yourself! It means stopping just short of failure – around two reps or so. In other words, although you don’t need to train to failure, you still need to train close to the point of failure.

How to do it

What’s the best way of knowing when to stop – ie to discern that you only have one to three reps left? A good way is to monitor the speed of your reps; as you approach failure point, you’ll notice your reps slow not just by a bit, but by a lot. In the study above, the participants were very experienced strength trainers (over 7 years), and the subsequent testing showed that the participants’ estimates of how many reps in reserve they had left in the bank were actually very accurate – on average within half a rep! Of course, you can also use a separate session to measure actual reps to failure using your chosen load then work from there.

Finally, it’s worth emphasizing that training close to failure or to actual failure shouldn’t be regarded as a mutually exclusive strategy. Instead, you can regard the approach as a continuum: when you want to ensure minimal post-training fatigue, you can terminate sets 3 or even 4 reps before failure. However, when you want to push hard (eg when you know the next day is a rest day), you can train much nearer to failure, or even to failure itself. The Aussie scientists in the study above produced an extremely helpful graphic summing up this continuum, which is shown below!

References

1. Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 871–877

2. Phys. Ther. Sport 2020, 42, 107–115

3. Sports Med. 2021 Jun;51(6):1245-1271

4. European Journal of Applied Physiology 2016. Volume 116 (1) 195-201

5. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 1991 Sep; 31(3):345-50

6. J Physiol. 2008 Jan 1; 586(1):35-44

7. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2006 Oct;31(5):530-40

8. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2002 Oct;12(5):288-95

9. J Physiol. 2008 Jan 1; 586(1):35-44

10. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2006 Oct;31(5):530-40

11. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 1991 Sep; 31(3):345-50

12. European Journal of Translational Myology 2017, 27(2), 6339

13. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 2019. 36(2)

14. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 2020. 34(5), 1237–1248

15. European Journal of Applied Physiology 2022. 122(5), 1111–1128

16. The Journal of Physiology 2016. 594(18), 5209–5222

17. Journal of Sports Sciences 2022. (12), 1–23

18. Sports Medicine 2022. 52(7), 1461–1472

19. Biol Sport. 2020 Dec; 37(4): 333–341

20. J Sports Sci. 2024 Feb 23:1-17. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2024.2321021. Online ahead of print

21. Science and Practice of Strength Training. 2nd ed. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2006

22. J Strength Cond Res. 2007;21(2):561–7

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.