Strengthen your endurance: time to go heavy for performance

John Shepherd looks at the most effective ways to use resistance training to improve endurance performance. The answers may surprise you...

John Shepherd looks at the most effective ways to use resistance training to improve endurance performance. The answers may surprise you...

When it comes to strength training, many endurance athletes quite naturally believe that they should perform endurance-based resistance training to enhance their endurance performance. A typical example of this is circuit training, using high rep and set numbers and with limited recovery. After all, this does seem to mirror the physiological requirements of their chosen activity. However, runners, cyclists or triathletes probably don’t realise the potential heavy load resistance training (HLRT) has to offer. HLRT is performed using low rep numbers and moderate set numbers, with good recovery. Crucially though, HLRT uses loads in excess of 80% of your one-rep maximum (1RM – the heaviest weight you can lift using strict form for one repetition).ATHLETE PROFILE: Mo Farah and heavy load resistance training (HLRT)

HLRT is probably most associated with sprinters and other power-based anaerobic athletes. However, it is increasingly being used by elite endurance athletes, such as Mo Farah – perhaps the greatest distance runner of all-time - with very positive results. The four times, 5000 and 10,000 metre Olympic champion works under the tutelage of Alberto Salazaar at Nike’s Oregon Project. Salazaar is a coach who likes to explore all available legal means to improve performance, and he gets Farah to train with strength and conditioning experts, who have him do HLRT. Salazaar has this to say about Farah’s S&C www.theguardian.com/sport/2013/apr/19/cmp-mo-farah-london-marathon: “Now, he’s (Farah) not just a skinny guy, he’s a strong wiry guy. And he’s not gained more than a pound or two since he’s started lifting heavy. People have always thought that distance runners should lift light. Don’t you believe it!” Apparently Farah can now squat one and a half times his body weight, 200lbs for 4-6 reps, and his recent results on the track speak for themselves.

Why go heavy?

Why should you go heavy? Well, everything else being equal, a stronger (and sometimes larger) muscle will have greater resilience, be more fatigue resistant and have better performance economy (PE). PE is a vital factor in all endurance events; an athlete who can run, cycle, swim, row and so on, using less effort at faster speeds will inevitably be a faster and better athlete. PE is a consequence of numerous factors, but strength and power are crucial determinants.In a previous article, we looked at why plyometric training can benefit endurance runners. In particular, the development of increased leg stiffness was identified as a positive outcome and determining factor for enhanced performance. Well, it happens that HLRT is a further influencer of leg stiffness. For runners in particular, enhanced leg stiffness can improve PE by boosting the energy-return capabilities of the legs. But studies show that PE is improved in cyclists and other athletes by using heavy resistance training. All this adds into the key rationale for HLRT building more endurance horse-power.

Many endurance athletes worry about lifting heavy and gaining unwanted weight (muscle) – weight that will need to be carried when running or cycling for example. However, as Salazaar noted with Farah, this is unlikely to occur for two good reasons. Firstly, the very nature of endurance training tends to maintain weight and with it muscle mass. Indeed, it may even reduce it, which may be unwanted and have negative performance effects. Secondly, the hormonal effects when endurance athletes weight train are not particularly conducive to weight gain (see panel below).

Panel: Hormones and weight training

Hormones are natural chemicals secreted in tiny amounts by the body, but which have a profound influence on the cells and organs in the body. The key ‘positive’ hormones associated with exercise are testosterone and growth hormone (androgens). Bodybuilders train to produce these hormones in copious amounts in order to build muscle size. Medium to heavy weights (70-80% of 1RM, for example), in sets of 1012 with relatively short recoveries are most likely to achieve this due to their ability to significantly elevate androgen production.However, HLRT of the kind recommended for endurance athletes is less likely to actually do this. Yes, it will release hormones, but not in the same quantities as the methods favoured by bodybuilders. Instead, it is able to boost the contractile properties of the muscles and engineer more power without significant hypertrophy (muscle growth).

Most readers will be familiar with fast and slow twitch muscle fibre. All these fibres contribute to endurance performance. Slow-twitch fibres are conventionally associated with endurance but fast-twitch fibres can also be trained to take on more of an oxidative function and therefore help enhance endurance performance at higher intensities (see figure 1). However, to really target the key fast-twitch fibres (Type IIAB), you need to be in the zone - focussed and generating high-powered electrical signals to stimulate their firing. It turns out that lifting a very heavy weight is the neural key that turns on these motor units. Switching them on by heavy weight training enhances power potential and PE when performing a sub-maximal activity, and results in lower increases in muscle mass gain www.thegaurdian.com/sport/2013/apr/19/cmp-mo-farah-london-marathon Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014 Aug;24(4):603-12. doi: 10.1111/ sms.12104. Epub 2013 Aug 5 J Strength Cond Res. 2013 Sep;27(9):2433-43. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318280cc26. Sports Med. 2016 Aug 6. [Epub ahead of print] J Strength Cond Res. 2014 Mar;28(3):689-99. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182a16d73.

Figure 1: Muscle fibre types

You can’t argue with science

Researchers are now confident that the reason HLRT improves endurance performance is because it improves leg stiffness, increases neuromuscular efficiency, and helps convert some of the body’s fast-twitch type IIb fibres into more fatigue-resistant, endurance-suited type IIA fibresScand J Med Sci Sports. 2014 Aug;24(4):603-12. doi: 10.1111/ sms.12104. Epub 2013 Aug 5.. A common problem with lab-based sports science studies is that they don’t use elite or high-level performers, nor are they able to test over a long-term period, to really see whether an intervention (such as HLRT is having an effect). However, one study that overcomes some of these potential shortfalls looked at concurrent HLRT and endurance trainingJ Strength Cond Res. 2013 Sep;27(9):2433-43. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318280cc26..Eighteen well-trained endurance runners, having VO2max scores in excess of 65ml/kg/ min (ie good aerobic power) were divided into three groups:

- Endurance group (EG) – these runners continued their normal endurance work and strength training with Thera-bands;

- Strength group (SG) – who did combined plyometric and resistance training workouts and their normal endurance training;

- Endurance - strength group (ESG) – who performed strength endurance weight training using loads of 40% of their 1RM with their normal endurance training.

When considering the effects of strength training, it’s important to consider the starting point of the endurance athletes involved. At the start, it is likely that any relatively systematic strength training protocol will be of benefit and lead to improvement, as the training is tapping into a previously undeveloped area. This almost certainly explains why in the above study, both ESG and SG groups positively improved various endurance qualities.

However, what this ‘general’ resistance training won’t easily do with endurance athletes is increase the ability to recruit more and larger fast twitch motor units. It’s this that is believed to produce a more significant boost to PE – and what Salazaar and Farah are pursuing by ‘going heavy’. This might explain why only the strength group in the above study saw performance gains.

More evidence

A number of research studies validate the ‘go heavy’ approach. One review study (a study that summarises the findings of a number of previous studies) evaluated the effects of concurrent HLRT on running economy (RE)Sports Med. 2016 Aug 6. [Epub ahead of print]. The team discovered that concurrent programmes had a small but beneficial effect on RE, and that HLRT and explosive (plyometric) training programmes produced similar RE enhancements (both HLRT and plyometric training tend to target larger fast twitch motor units, which should explain the benefits for both methods). It was also found that the longer the training intervention, the greater the benefits for RE.Another team of researchers looked into the effects of endurance strength training, HLRT and explosive training on endurance performanceJ Strength Cond Res. 2014 Mar;28(3):689-99. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182a16d73. The research involved a 16-week period where two groups of recreational endurance runners (split according to gender) performed HLRT and explosive training plus their endurance training. Two other gender-split groups of runners acted as controls – but interestingly, carried out circuitbased endurance workouts.

The results showed that the mixed strength training (HLRT plus explosive work) was more effective than circuit training in terms of benefitting overall fitness. Specifically, they observed improvements in maximal strength and running economy in both groups – but additionally saw an increased maximal speed in the mixed strength group.

However, the results of this study once again highlight the problem of introducing a strength training protocol in a group/groups of endurance athletes with little or no prior specific experience of resistance training – ie, virtually any kind of strength training may produce performance gains in those who have previously not strength trained – particularly to begin with.

Putting theory into practice

Endurance athletes may have limited time to resistance train – particularly when the season gets underway – so getting the most out of workouts is crucial. As such, it’s better to ‘attack’ a short time-span workout and focus on just two to three key exercises. Key exercises for runners and cyclists for example would include squats, step-ups and high pulls/ cleans. Box 2 below shows the key principles you should adhere to when performing HLRT.Box 2: Key principles of HLRT

Weight loading - How much weight should you lift? Well, after a relevant warm-up (which should include a light set [50-60% 1RM] of 6-10 reps of the exercise being performed), the aim should be to lift a weight chosen so that it is only possible to do so 1-6 times. This will range from 80% to 100% of 1RM. Here are some session protocol examples (sets x reps):- 4 x 3 @ 90% 1RM

- 3 x 2 @ 95% 1RM

- 4 x 4 @ 85% 1RM

- 3 x 6 @ 80% 1RM

Frequency – Connected to the above, it is better to perform HLRT in a rested state – eg not the day after a long or hard endurance session. one to two heavy weight sessions in every 10-day training period should be enough for most athletes. once a good level of strength has been developed, your goal should then be to maintain your newly acquired strength.

Focus – When performing HLRT sessions you need to be fully focussed on the job ahead as indicated. You must really want to lift the weight, and attack it when doing so. It is this movement of the weight as quickly as possible (obviously safely) by supplying a charge of neural energy that is key to recruiting the largest and most powerful of fast twitch motor units. Control must also be used in returning the weight to the starting position.

Essential HLRT exercises

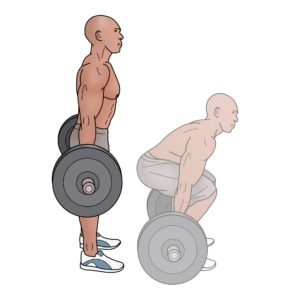

*Squats (see figure 2)

You’ll need either a squat rack or a Smith machine. If you’re not using a Smith Machine, it’s also advisable to have spotters on hand, especially when lifting above 90% of your 1RM. The key with the squat movement is to keep the weight of the bar over your movement as you lower and lift up. Imagine that you are trying to sit on a chair behind you. Try to lower to close to half squat and then explode up.Figure 2: Barbell squat

Single leg variants are very beneficial too and may initially be easier to perform by holding weight plates or dumbbells at arms’ length. Hack squats (figure 3) - where the bar is held at arms’ length behind the thighs and taken from an elevated position – are useful too. This is because the back is less subject to loading, which can be an injury worry.

Figure 3: Hack squat

*Step ups

Step ups (see figure 4) can also be performed with a knee drive from the non-stepping leg to perform a step-up drive. At the bottom of the movement, the non-stepping leg is brought to a position parallel to the floor then the drive upwards takes place. Whichever version is performed, it is vital to maintain a strong and braced core.Figure 4: Step-ups

*High pulls (see figure 5)

This is a dynamic triple-extension exercise. When pulling the bar from the floor, it requires a really explosive and dynamic extension through the ankles, knees and hips – a movement that carries over well to running. It is performed as follows:- Stand with feet slightly wider than shoulder-width and with toes under the bar.

- Squat down keeping your heels on the floor.

- Take hold of the bar with an evenly spaced over-grasp grip and turn the elbows out slightly.

- Get into the start position by extending your legs so that your arms are straight. Your back should be flat and your gaze straight ahead.

- To move the bar, drive up from your legs (do not use your arms to pull on the bar). Your torso will move back.

- As the bar passes your hips, drive them forwards as you lift up onto your toes. This will add momentum to the bar.

- Now you can introduce your arms to pull the bar up to shoulder-height. Ensure that you take your head back, to avoid possible contact with the bar.

- As the upward vertical speed of the bar drops, catch its momentum and ‘follow’ it to control it back to the ground.

- As mentioned, you can drop the bar if difficulties are encountered.

- If necessary re-set your starting position each time. Do not rush your reps.

Figure 5: High pulls

You need to be logged in to continue reading.

Please register for limited access or take a 30-day risk-free trial of Sports Performance Bulletin to experience the full benefits of a subscription. TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.