You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Team sport strength training: weighty matters

SPB looks at new research on strength training for team sports; can bodyweight exercises match the gains achieved in the gym?

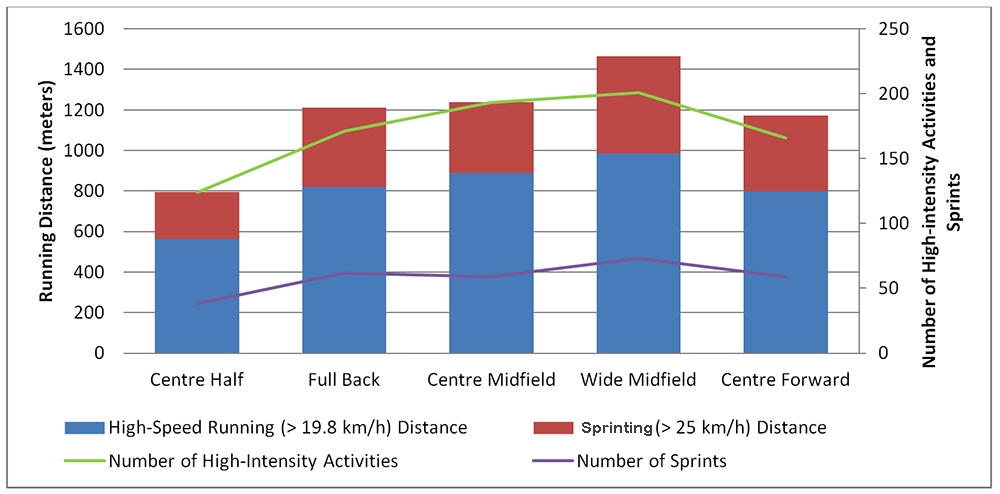

Strength training is considered a key strategy to improve performance in team sports such as soccer, rugby, basketball etc, and with good reason; a large body of research shows that there is a direct relationship between strength levels and the high-intensity actions (eg sprinting and jumping) which underpin performance in these kinds of sports(1,2). In soccer for example, the intermittent nature of the sport involves various sporadic but high-intensity actions such as changes of direction, high-intensity running, sprinting and jumps(3).The important of high-intensity capacity in team sports

Although much of the energy expended on the pitch during a game occurs during walking, jogging and running, the total distance covered during a soccer game is actually a poor gauge of the physical demand placed on a player. Instead, it is the distance covered performing high-intensity running/sprinting/jumping that is a more valid and reliable indicator of a player’s performance capability – even though it constitutes a much smaller proportion of a player’s activity profile (see figure 1). Data gleaned from research into soccer players shows why this is the case(4):- During the second half of a game, the volume of high-intensity running can be 35 to 45% less than in the first half without a reduction in low-intensity running.

- Elite soccer players run further at a high-intensity during a game than moderate-standard players.

- It is during high-intensity periods of play that the outcome of a game is often decided.

Figure 1 – Positional breakdown of workload intensity during an English Premiership game(4)

The total distance covered during a game while performing such variable activities typically ranges from 10 to 12km. High-speed running and sprinting form a much smaller proportion of distance covered; however, players’ performance in these aspects often determines the outcome of games.

What kind of strength training?

If sprint, jump, change of direction and other high-intensity metrics are critical for performance, and if strength training improves these qualities, the next question is what kind of strength program is effective and easily implemented in a team setting such as soccer, rugby, basketball etc? it turns out there’s more than one way to skin a cat; a trawl through the published literature shows that there are in fact a number of different strength training methodologies that can improve physical performance in soccer and other team sports. These include:- Traditional weight lifting with free or machine weights(5).

- Eccentric overload training (see this article for a detailed discussion on eccentric training)(6).

- Plyometrics training(7).

- Ballistic exercises(8).

- EMS training (see the article elsewhere in this issue)(9).

- Olympic weight exercises(10).

- A combination of some of the above methods(3).

Self-loaded strength exercises

When using weight training equipment is not possible, another option is to utilize ‘self-loading’ resistance exercises – ie where the athlete uses his/her body mass as the loading mechanism (eg, press ups, chins, dips, bodyweight squats and lunges etc). But how effective is self loading for strength development? If we look at the previous research, we can find studies showing strength training based on self-loading significantly improves strength performance(11,12). Even better, research also shows that strength training based on self-loading is easier to apply in practice than many of the methods outlined above(13,14). In addition, self loading exercises are seen as being more flexible, cheaper, quicker, and easier to implement on a day-to-day basis.The question of course for soccer and other team-sport athletes is how effective could self-loaded strength training be for improving key aspects of high-intensity performance compared to more traditional methods? Is it really up to the job? To date, no detailed research has been carried into this topic. However, a brand new study carried out by a team of Spanish and Portuguese researchers has just been published in the journal ‘Frontiers in Physiology’ and provides some definitive answers for team sport players and their coaches seeking alternative methods of developing strength gains(15).

The research

The researchers set out to examine the effects of two different strength programs – one using self-loading vs. one using conventional overloading (ie using free and machine weight exercises) - on selected measures of soccer-relevant physical performance ( jumping, aerobic endurance, and body composition) in young male soccer players. In particular, they wanted to find out whether the overload training would produce superior results to self-loading, and if so, by how much.In this study, 144 U16 and U19 players undertook a 15-week program of strength training. The players were divided into two groups, both of which contained a mix of U16 and U19 players:

- The overload group – 75 players who performed their normal soccer training plus two strength sessions per week using traditional weight training to generate (over) loading.

- The self-loading group – 69 players who performed their normal soccer training plus two strength sessions per week using bodyweight exercise to generate loading.

- Countermovement jump performance - Three jumps were performed, with a recovery time of 20 seconds between jumps and the average of the three jumps for analysis.

- Aerobic endurance – assessed by the ‘30–15 intermittent fitness test’ which consists of 30-seconds of shuttle runs, interspersed with 15-seconds of passive recovery periods. Velocity was set at 8kmh for the first 30-second run and was increased by 0.5kmh every 45-second stage thereafter.

- Body composition – to assess lean body mass and body fat % (using bioimpedance analysis - BIA).

The training program

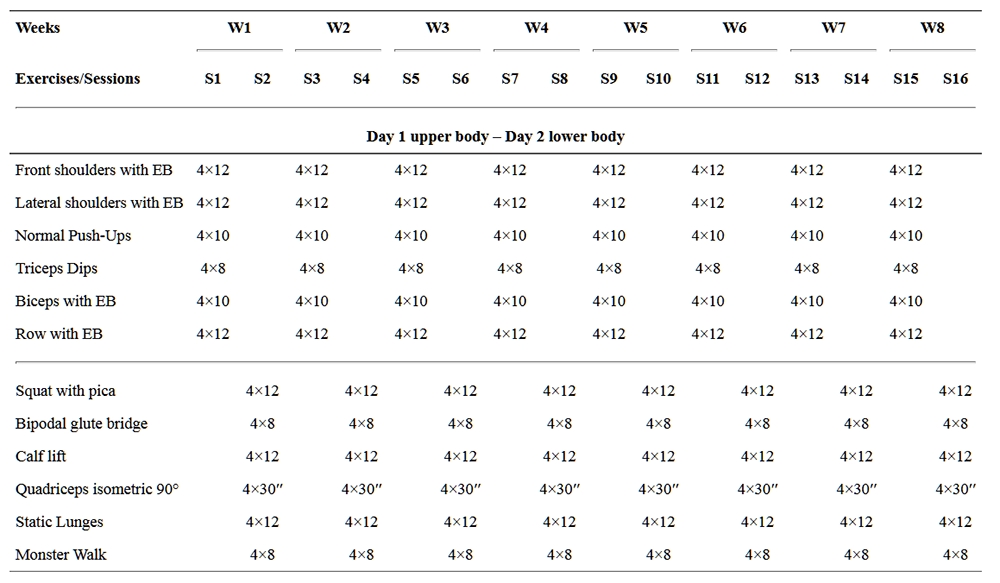

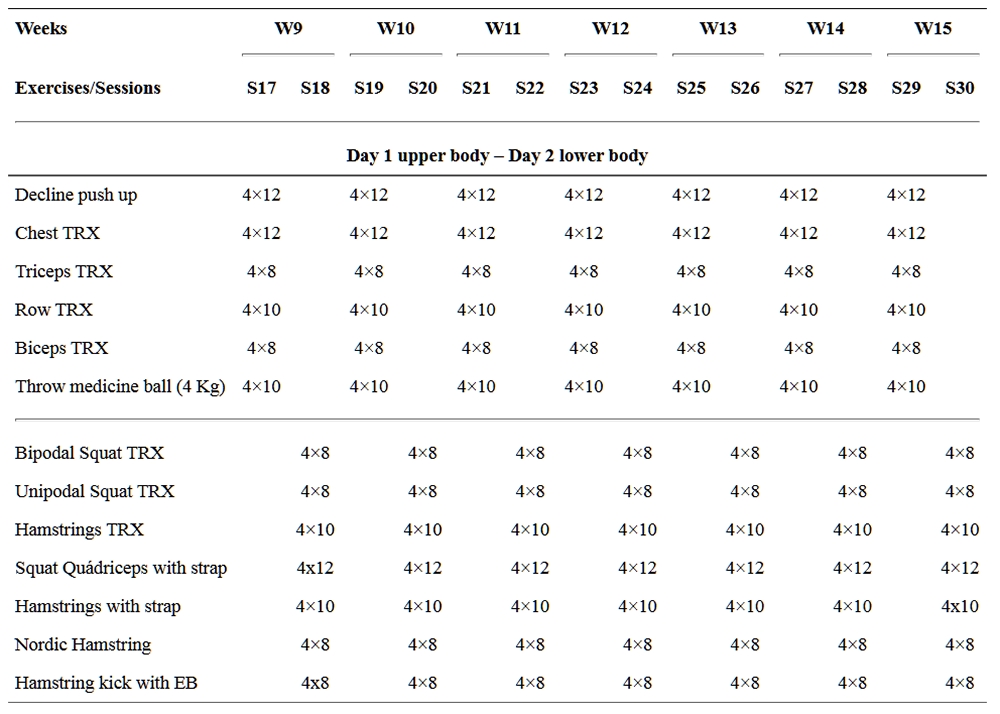

The subjects performed five normal training sessions (soccer-specific training on the field) plus two strength sessions per week carried out in a training circuit format. In both groups, session 1 was for the upper body and session 2 for the lower body.For the self-loading group, intensity used was the body weight or body weight plus light resistance provided by the player. This training was performed on the artificial grass (the same used for competition), with the subjects wearing normal soccer boots and clothing. For each exercise, four sets were performed using repetitions of 12, 10, 8 and 8). Rest between sets was one minute.

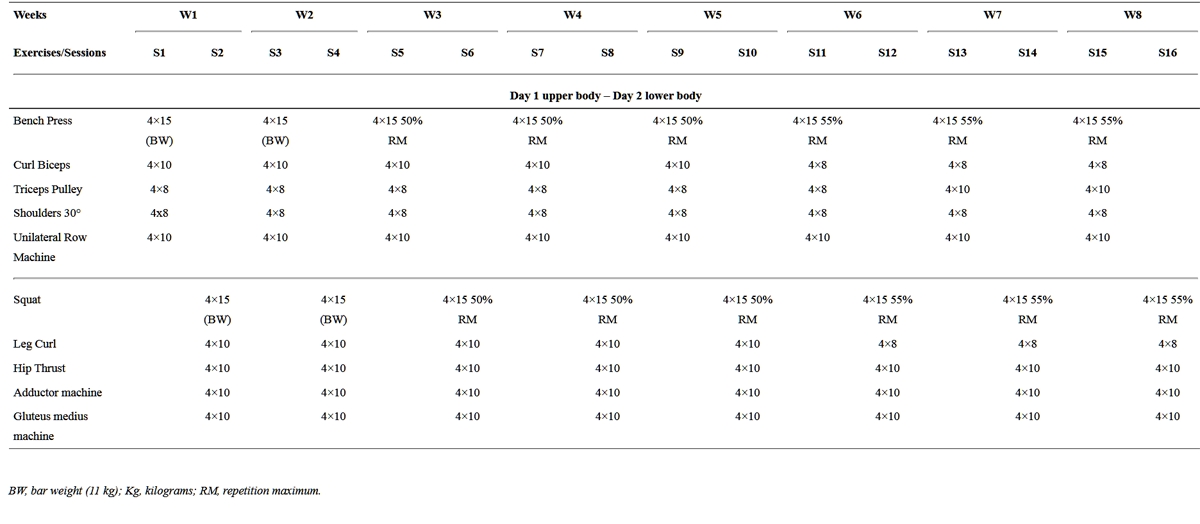

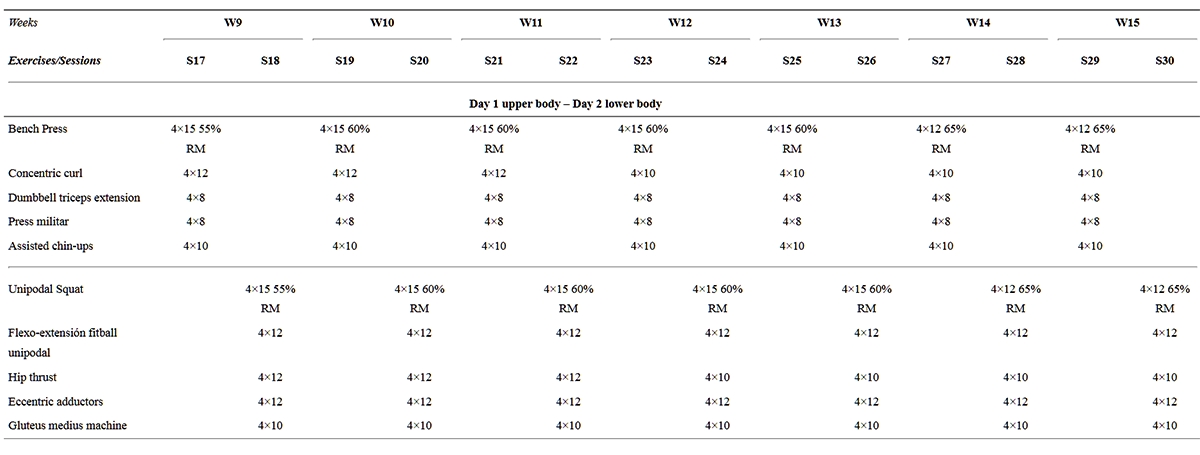

The overload group performed strength training in the gym. The external overloads for the bench press and squat exercise were between 50 and 65% of the 1-rep max (1RM). For the rest of the exercises, the players used an appropriate weight that enabled them to complete the sets and prescribed repetitions with the correct execution technique. Depending on the exercise to be performed, four sets were performed with maximum execution speed, using repetitions of 12, 10, 8 and 8 reps. Rest between sets was one minute. Both groups progressed their training exercises so that after eight weeks (end of phase 1) they moved onto a slightly more challenging set of exercises for the next seven weeks (phase 2). The exercises and sets/reps for phases 1 and 2 for both groups are shown in tables 1 to 4 below.

Tables 1-4: Training exercises used in the intervention

(BW = bodyweight; EB = elastic band; RM = rep max; TRX = a method of suspension training using straps that dangle from a hook overhead, and which requires extra coordination and core strength)

Self-loading phase 1

Self-loading phase 2

Overload phase 1

Overload phase 2

What they found

The key findings were as follows:- Both the self-loaded and overload programs results in very significant improvements in countermovement jumping ability, aerobic endurance and body composition.

- The gains achieved in aerobic performance (3.5% improvement in self loading, 3.1% in overload) were deemed to be similar, regardless of the type of strength training performed.

- Body composition changes were less clear cut; while the % reduction in body fat was greater in the overload group, it was the self-loaded group that gained more lean muscle. Taken overall, it was concluded that both interventions had produced similar beneficial gains in terms of soccer performance.

- While the self-loaded training produced very significant gains in jumping performance (7.4%), it turned out that the overload training produced even greater gains – around 9.9%.

Practical implications for players and coaches

This study is significant because it’s the first research carried out that compares self-loaded and overload strength training methods for young soccer players, and it shows a significant benefit in the key variables known to be important for soccer performance. Moreover, these findings are highly likely to be relevant to other team sport players, where high speed running, changes of direction and jumping movements are an essential element of play.For coaches who are looking to implement some kind of strength training for players, the self-loading protocol is ideal, because it can be performed on the pitch without the need for special equipment or access to a gym. All that is needed is that players understand the correct technical execution of the exercises. A good place to start implementing such a program is to look at the self-loading protocol outlined above in tables 1 and 2 (a larger version can be found here for table 1 and here for table 2). Depending on the experience and fitness levels of the players, the number of exercises and sets per body part could be truncated while players find their feet!

References

- J Strength Cond Res. 2014 Jul; 28(7):1839-48

- Int J Sports Med. 2019 Nov; 40(12):796-802

- Apunts 2 72–93. 10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2018/2).132.06

- Managing high-speed running load in professional soccer players’ SPSR 2019 March (53) volume 1

- J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2016 Nov; 56(11):1269-1278

- Sports (Basel). 2019 May 5; 7(5):

- J. Exp. Biol 2012. 2 2348–2351

- J Sports Sci. 2020 Jun - Jun; 38(11-12):1416-1422

- J Strength Cond Res. 2010 May; 24(5):1407-13

- J Strength Cond Res. 2008 Mar; 22(2):412-8

- J Strength Cond Res. 2016 Jun; 30(6):1540-6

- Biology (Basel). 2020 Nov 7; 9(11):

- Sports Health Res 2020. 12 112–125

- PLoS One. 2019; 14(7):e0219355

- Front Physiol. 2021; 12: 771684.

Related Files

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.