You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Energy-return running shoes: do they deliver the goods?

Do running shoes with high energy-return characteristics really improve performance, and if so, in what ways?

Endurance running performance has been traditionally associated with several physiological variables, including something known as ‘running economy’ (RE)(1-3). For those unfamiliar with the concept of RE, it refers to how efficiently the muscles are able to utilize oxygen delivered to them by the cardiovascular system in order to provide the energy required to generate forward motion during running (more technically defined as the steady-state oxygen uptake at sub-maximal running speeds).Importance of RE

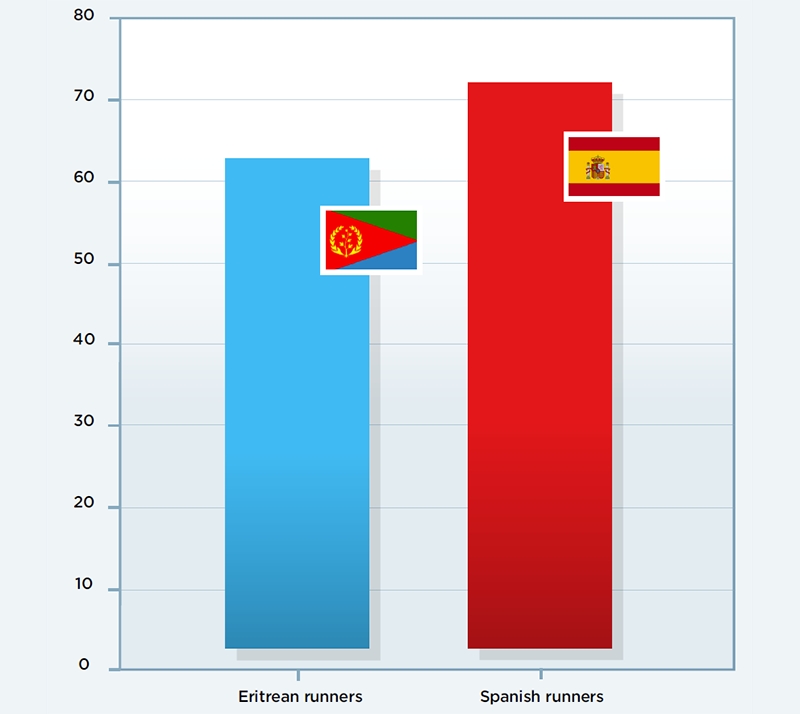

RE is considered important for performance because all other things being equal, a runner with high levels of RE is able to sustain higher exercise intensities and/or maintain the same exercise intensity for a longer period of time compared to a runner with poorer RE(4). Evidence for this can be seen in marathon performance where the key difference between world class athletes and ‘merely’ elite athletes is that the former tend to have exceptionally high levels of RE despite maybe having lower absolute maximum levels of oxygen uptake.For example, in one study, researchers compared elite Eritrean runners with elite Spanish runners(5). Although both groups had very similar maximum aerobic capacities, the researchers were mystified as to why the performances of the Eritrean runners were consistently better than those of the Spaniards. Testing on both groups revealed that the key physiological difference was the exceptional running economy of the African runners; at 21kmh (13.0mph), the Eritreans needed to consume just 65.9mls of oxygen per kilo per kilometre - compared with 74.8mls of oxygen for the Spanish runners (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Oxygen consumption per kilo per kilometre at 21kmh(5)

The Eritrean runners’ superior running economy meant they needed 13.5% less oxygen per kilo of body weight to maintain a marathon pace. This explained much of their performance advantage over their Spanish counterparts.

Improving RE

Improving RE is linked to therefore to better performance, and the most obvious way to do this is to perform regular running training. However, there are other ways too. In the last 15 years or so, research has shown that strength training also boosts running economy (see this article for a fuller discussion)(6,7). Yet another factor that affects RE is shoe design; previous studies have shown that running shoe characteristics can play a significant role on the energy cost of running. For example, minimalist shoes (ie with reduced shoe mass and heel drop) have been shown to yield significant improvements in RE (around 1-4%) compared to conventional heavier shoes with thicker EVA (ethylene vinyl acetate) midsoles(8). Another design factor that affects RE is a shoe’s midsole characteristics. Wunsch et al. showed that a leaf spring-structured midsole acutely improved RE by around 1%(9), while a new midsole material composed of thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) has been used to enhance energy return during running – potentially increasing RE by as much as 4.1%(10,11).Does improved RE always mean improved running performance?

Despite the remarkable findings from previous studies showing that both TPU and minimalist shoes can reduce the oxygen cost of running compared with conventional shoes, it is still unknown whether the use of these RE-boosting types of shoes automatically translates into better running performance. Although the theory says they should, there’s actually a dearth of evidence to demonstrate they actually do. But now a new study by Brazilian scientists has provided some really useful insights for runners who may be considering purchasing high energy-return shoes(12).Published in the Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research, this study investigated whether improved RE through shoe use translated into better running performance by:

- Comparing the effects of TPU and minimalist shoes on the oxygen cost of running.

- Analyzing the effects of any improvement in RE produced by the shoes on running performance.

What they did

In a nutshell, the researchers recruited eleven recreational runners who had to perform two sub-maximal constant-speed running tests and two 3km time-trials with each of the two shoe models. The runners’ oxygen uptake levels were measured during the sub-maximal constant-speed running tests in order to determine their RE at 12 kmh, along with each runner’s oxygen cost of running at their average speed sustained during the 3-km running time-trials. The constant sub-maximal speed tests were performed using a motor-driven treadmill while the 3km time-trials were performed outdoors on a 400m running track.What they found

The key findings were as follows:- Compared to the minimalist shoes, the TPU shoes resulted in better RE (by around 4%) in the sub-maximal running test at 12kmh.

- When it came to the 3km time trial at maximal pace, the oxygen demand while running was similar regardless of the shoe worn – ie at this higher speed, there was no difference in RE between the shoes.

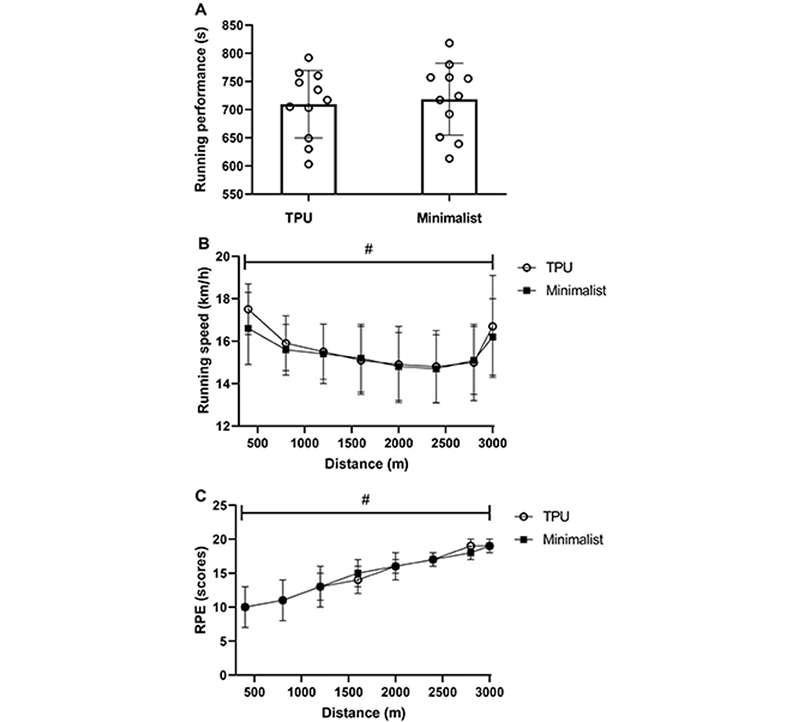

- Another finding in the 3km time-trial was that the were no significant differences in terms of each runner’s overall performance, running speed distribution, and perceived exertion responses between the TPU and minimalist shoes (see figure 2).

Figure 2: Comparison of the runners’ overall performances (A), running speed distributions (B), and perceived exertion responses (C)

Open circles = TPU shoes; closed circles = minimalist shoes. The differences were so small between the two shoes that they were statistically insignificant. NB: Vertical lines through points on the graph are error bars, which describe the error or uncertainty in a reported measurement.

Implications for runners

The key finding here was that while the TPU shoes improved RE during sub-maximal running, when the pace was upped to the runners’ maximums for the 3km time trial, the TPU shoes lost their ability to provide an advantage in RE. This no doubt explained why the runners’ 3km performances and perceived levels of exertion were no different in the two shoe conditions. Would either of these shoes have been better than a normal running shoe (ie not low-mass minimalist or one with a TPU midsole) in the 3km test? Unfortunately, this study didn’t include that condition, which is a shame. However, given the evidence cited above it’s very likely that a normal running shoe would not have fared as well in the sub-maximal running test. We also need to remember that the runners in this study were recreationally trained rather than elites; the results may have been different for runners performing at a higher level.In terms of what this means for shoe choice, this study adds further evidence that (in recreational runners at least), running economy during lower-speed running is significantly improved with the use of TPU shoes. This in turn implies that runners aiming to complete a long-distance event such as a marathon or ultra marathon, where longer-duration, slower-paced running is the name of the game, may gain significant benefits using TPU shoes. However, for shorter duration, higher-effort runs, these gains may be less or even non-existent. However, the demands of distance running on the body should not be underestimated; just as when normal shoes are selected, any TPU shoe should also be supportive enough and cushioned enough to ensure the risk of injury is minimized and running gait is optimized. A visit to a dedicated running shoe retailer with professionals on hand to advise is therefore recommended over purchasing online and hoping for the best!

References

- Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1992;24:483–489

- Sports Med. 2004;34:465–485

- J Strength Cond Res. 2014;28:1688–1696

- Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48:2175–2180

- Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2006 Oct;31(5):530-40

- Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008 Jun;40(6):1087-92

- J Strength Cond Res. 2006 Nov;20(4):947-54

- Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44:1335–1343

- Eur J Sport Sci. 2017;17:303–309

- J Sports Sci. 2016;34:1094–1098

- Mov Sports Sci. 2015;80:39–49

- Braz J Med Biol Res. 2021 Mar 15;54(5):e10693

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.