You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Sports technology: time to take back control!

Sports psychologist Josie Perry explains how endurance athletes can derive the psychological upsides of technology in sport, while avoiding the pitfalls

Every athlete wants to feel mentally tough when they train and compete. Athletes also, crave the way mental toughness the helps us bounce back from disappointments, keep perspective and stay confident when we have bad races and allows us to train and perform with consistency and commitment. We want to feel in control of difficult or pressurised situations, and to see competitions as challenges rather than threats. As mental toughness is so key to performance we are always looking for shortcuts to increase it. In this article, we ask whether technology can provide that shortcut?You can often spot an athlete by the bling on their wrist. Not a Rolex watch or Tiffany bracelet, but a GPS tracker. Sports technologies like GPS watches are big business. Thirty percent of the US population are said to have one. And my own research has found that these types of are owned by 93% of UK endurance athletes. The ‘quantified-self’ movement, covering trackers like this, began as a niche market but has been taken over by the big corporates and is now estimated to be worth over $60 billion. Research is finding that these tools are beneficial for many of the 39% of the world’s population who are overweight with social networks(1) and gadgets(2), helping people exercise more(3) and develop healthier habits(4). But most endurance athletes don’t need that push to exercise or social engagement to help them hit government targets on weekly activity. So, what are athletes using, and what are they using them for?

What athletes use

Some technologies are mass-market gadgets re-purposed for sport – for example GPS watches, pedometers, virtual reality headsets, social media, forums, Whats App groups etc. Others were originally designed for the medical markets like Sleep or Heart Rate variability monitors, while some have been designed specifically with athletes in mind – eg power meters, which are becoming increasingly popular – either as integrated into equipment components, or as ‘bolt-on’ additions (see figure 1).Figure 1: Pioneer power meter

Pioneer makes affordable and dual-sided crank meters, which have been received favourably by cyclists. An unusual feature of the Pioneer system is it not only measures force, but direction of force too. Twelve measurements per revolution allows force display in real time, which allows for analysis of pedal stroke.

All of these devices generate a huge amount of data (heart rate, distance, time and speed as a minimum) that can be used to analyse performances both from training and racing. As well as the formal data, coaches and athletes are using technology to communicate quickly and effectively; sharing race plans or details over social media or setting up WhatsApp groups of athletes to motivate each other.

Are you overwhelmed?

If you are not picky about what you want to use and understand why, all this data can be overwhelming. I recently set out to study how ultra-endurance athletes (marathon runners, long distance cyclists, swimmers and triathletes) use technology in their sports. Two hundred and fifty five athletes completed an online survey, and six of those who use a lot of technology gave interviews about how they perceive the benefits and pitfalls of using so much technology in their training and racing.What emerged was that those using lots of technology were more likely to be triathletes, in their sport a long time and that they train more than the average ultra athlete (who trains for around 10 hours a week). There is no causal factor here, so it may be that using technology keeps them in the sport longer, or pushes them to increase their levels of exercise. Or it may be that those who have been competing for years and love doing lots of hours of training are more serious about their sport and feel they can justify spending time and money on the technology they want.

In talking to so many endurance athletes, and in studying the published papers of those who also research this area, it seems there are some real benefits - but also risks - to incorporating technology into your training and racing. Managing the risks and maximising the benefits can therefore give a real boost to your mental toughness.

Goals

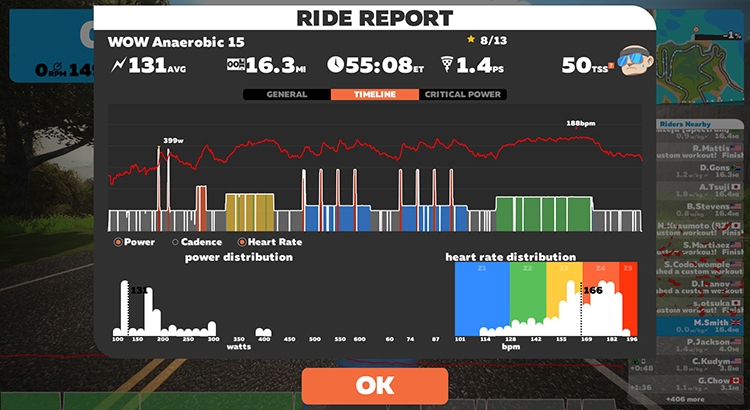

Most sports technologies are built around so-called ‘gamification’ - a design feature which draws you back to the tool and increases your adherence to using it. This concept plugs into perfectly to the goal-driven nature of athletes where they focus on turning planned sessions from red to green (Training Peaks), win kudos or be marked as the fastest (Strava), or win virtual upgrades and power scores (Zwift – see figure 2). Gamification can very effective when the games or sessions are aligned with your own goals. Unfortunately however, many athletes find themselves drawn to deviate from their ‘real-life’ goals and start to compete with others through virtual challenges (such as the ‘Rapha Festive 500’ or ‘Run Every Day in January’), which risks harming performances in the real-life races they actually care about!Figure 2: Zwift power scores

A screen grab of a post-ride breakdown showing various parameters such as power, heart rate and cadence.

Key learning point

To use technology to help you stay focused on your goals and be consistent in training, complete a goal setting session before you start your season. Being really clear on your overall goal for the season, the performances you’ll need to put in place to achieve it, and the processes you need to follow will help you stick to your real life plans. It also sets boundaries so you don’t get carried away by online challenges.Community

The mentally tough athletes I have researched all say that to do well in their sport and go at the right intensity, they need to train alone. This may be physiologically beneficial but can leave athletes mentally rather isolated and lonely. By sharing data on technologies like Strava, engaging in debates on forums or twitter or checking in with other athletes in Whats App groups, athletes reported they were able to feel part of an online community and benefit from enjoyable and supportive friendships. This works very well when you’re fit and healthy. However, if you get injured, engagement with the online sports community can actually increase your isolation and create feelings of jealousy or despondency. Additionally, if you use sport as a coping mechanism for a mental health issue (as some do), then not being able to train, and losing all support mechanisms at the same time, can exacerbate the original problem.Key learning point

Decide how much of yourself you want to share with online communities. These groups can help boost your resilience if they provide support. But keep in mind that if you get injured, you’ll need some non-sporty friends too! Use online communities in a way that supports your goals but remember there is always a mute button so you don’t lose all confidence and emotional control when injured.Brutally honest feedback

The feedback we get from others on social media or the data we draw from our trackers can be helpful and motivating. Competitive athletes, or those who thrive from external validation of achievements, find huge benefits from the feedback. Those who feel they take shortcuts find the black and white nature of the data means they can no longer gloss over poor outcomes. It forces athletes to make sense of their performances and allows coaches to keep greater account of their athletes.But this comes at a price. If it is the only means by which an athlete starts to understand their performance then it may offer an incomplete representation of the situation, failing to take into account the environmental, logistical and health variables which genuinely impact on an athlete(5). Such blunt and public analysis can also cause immense pressure as it prompts self-reflection and raises self-awareness.

Some athletes can use this pressure helpfully as an impetus to train harder, or to fight malaise if they are feeling unmotivated. Others however may find themselves continually thinking about how a session will look and fear being judged. Almost every athlete I interviewed said this fear of judgment meant at some point they had trained harder than they were supposed to, which in some cases had caused injury, burnout or meant they missed their main goal.

Key learning point

The self-awareness we can develop from feedback can be very helpful at forcing us to be honest about how hard we are working. If we aim to learn from our feedback we can develop a mentally tough mindset and improve. If however, we continually judge ourselves against our own data and that of others, we can become very disillusioned. So whenever looking at data, ask ‘What can I learn’? Do not ask ‘What did I do wrong’?Data overload

Having so much technology to rely upon can dehumanise us in our own minds, and in the minds of our coaches. Researchers at Bath University argue that technology can threaten an athlete’s learning potential if coaches develop a ‘machine mentality’ and start to view athletes as pieces of data rather than humans(6). Athletes then feel under surveillance, reducing their autonomy. This can dampen their intrinsic love of their sport, and pushes them to robotically complete a session even when terribly fatigued. This robotic mindset means that athletes relying too much upon technology can become poor at reading and translating the signals coming from their own body. Previously astute internal monitoring techniques may fail, and athletes question themselves - either holding back when they don’t need to or pushing themselves when too tired.Key learning point

Even if you love your technology pick a couple of sessions a week where you train ‘naked’ without any tech. Spend some time in those sessions ‘body checking’; running up and down your body in your head listening to the signals each part is giving you. Also spend some time just enjoying the scenery and environment around you, forgetting about pace or precision and remembering why you love to train.Adherence to exercise

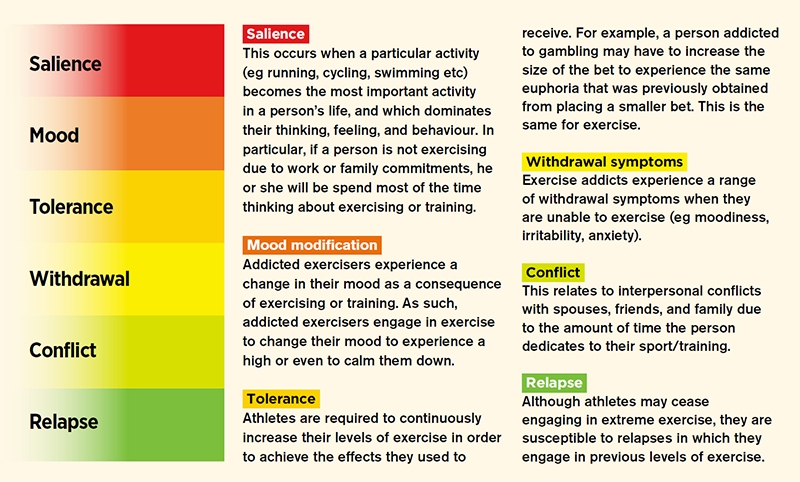

The stickiness of these technologies is great at keeping us focused and goal driven so we stay motivated. However, for most athletes reading Sports Performance Bulletin, motivation will already be high. The fear for athletes at this level is that technology makes you over adhere to exercise, so you risk becoming addicted. My research found this to be the case; that the more technology an ultra-endurance athlete is using, the higher the risk of exercise addiction. The particular types of technology found to have a significant impact on addiction risk were GPS watches, online trackers and being involved in WhatsApp groups for your sport.Figure 3: Six indicators for exercise addiction

Key learning point

There are six key indicators of exercise addiction (see figure 3 above). Awareness of what they are, and a regular check in with yourself to see if you are hitting too many of these will be good way to keep your sport in perspective and not taking over your life. The areas to think about are how much exercise you are doing, do you feel you need to increase the amount you do, do you use it to improve your mood, do you feel bad when you can’t exercise, do you try to cut back and find you can’t and, most importantly, is it causing conflict with others?Five essential questions to ask yourself when tempted by a new piece of technology

- What is the benefit of using this?

- What could be harmful to me (mentally or physically) about using this?

- Am I using the data I get from this in a way that means I’m comparing myself to others?

- Will the data I generate be in the public domain, in a way that concerns me?

- Will this technology add lot of extra time onto my training?

Case Study #1: Gary Laybourne, the tech fanatic

Gary Laybourne is a GB age-group triathlete and BTF Level 3 coach with South London Harriers. He is passionate about using technology in his training. As he explains: “As a sports science graduate and someone who has been involved with coaching for the past 15 years or so, I have always looked for those tangible and evidence based performance indicators. I have become much more engaged with tech and the use of social media to improve knowledge and performance.

My regular tech 'go tos' are my Garmin 920XT watch, my Edge 1000 and a Quarq power meter, which then ultimately leads to me poring over the Garmin Connect data! I upload my training to Train Xhale to periodise and review my training and I use Strava regularly - but genuinely more as a social media type tool to stay in touch and banter with other athletes than cry over who took my KOM!

In racing I have slowly moved to using tech, mainly for post-race review but more so over time just gaining that extra reassurance every now and again that I am pacing myself correctly. However, if after a certain period of time has passed and I am feeling great, I'll start to disregard the numbers as they can also start to hold you back.”

Case Study #2: Rhian Ravenscroft, the tech avoider

Rhian Ravenscroft is a triathlete who runs the female kit company ‘Thero’. More recently, Rhian has cut back massively on the amount of technology she uses for her training. Rhian elaborated: “I'm coming back from a long injury and am finding that I am putting too much pressure and stress on average pace, mileage and how slow my runs are (especially knowing this will show up on my Strava). It’s also dispiriting to see my slower times in certain segments on Strava compared to what I was running pre-injury. It’s a constant reminder of how far there is left, and not instead of how far I have come. I have therefore decided to worry less about stats and try focus on the why and the how of running. I am constantly amazed by how much information people have, and by how many stats they have to hand. To me, it makes running seem very complicated when really it is the simplest form of enjoyment there is!”

Summary

Technology has seeped into every part of our lives and, for many athletes it is playing a key role in their sport too. Using it to dictate your training, striping yourself down into machine processing data rather than a human with a busy life and sporting passion will see the technology weaken you, until you become mentally fragile. Using it intelligently to learn from (eg when you have a poor performance), to maintain perspective and confidence, to stay in control of tough situations, to maintain consistency in training and to develop a mindset where you can turn threats into challenges will make you a mentally tougher athlete and achieve the performances that you deserve.References

1 - Preventive medicine reports. 2016. 4: 453-4582 - J Med Internet Res. 2015 Jul; 17(7): e174

3 - Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015.12(1): 414-427

4 - JAMA. 2015. 313(5): 459-460

5 - Sport, Ed and Society. 2017. 22(8): 919-931

6 - Sport, Ed and Society. 2016. 21(6): 828-850.

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.