You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Triathlon training: yes or no to wetsuits in the pool?

SPB looks at recent research on wetsuit use when swim training and explains why caution is required when triathletes train in the pool

One of the golden principles of training is specificity. In short, this means your training should be as specific as possible for the demands of your competitive event. A lot of the time, this is glaringly obvious; you wouldn’t train for a marathon by cycling, or train for a 400m freestyle event in the pool by performing backstroke sessions in the sea!

However, the specificity principle goes a lot deeper than this. For example, if you are training for a hilly or mountain marathon, you need to perform a chunk of training on the hills or in the mountains. Likewise, if you’re training for an open-water 400m freestyle race, you need to ensure your training includes open water sessions in order to learn how to cope with colder, choppy waters, where there are no lane lines to guide you and the psychology of knowing that the inky dark water below you can be very deep and shared with many other creatures!

Triathlon swimming

One of the main challenges and/or appeals of triathlon competition is competing in open water, where simply being a good swimmer in the pool is not enough – for all the reason given above. Physiologically, the biggest of these challenges is cold water. Since water conducts heat away from the skin nearly 20 times more effectively than air, temperatures that are absolutely fine for terrestrial training can cause major problems when the body is immersed in water. For example, running outdoors in cool/cold conditions of 5C (41F) is near ideal for maximum marathon performance(1). However, when immersed in water at 5C, progressive heat loss occurs and hypothermia begins to set in.

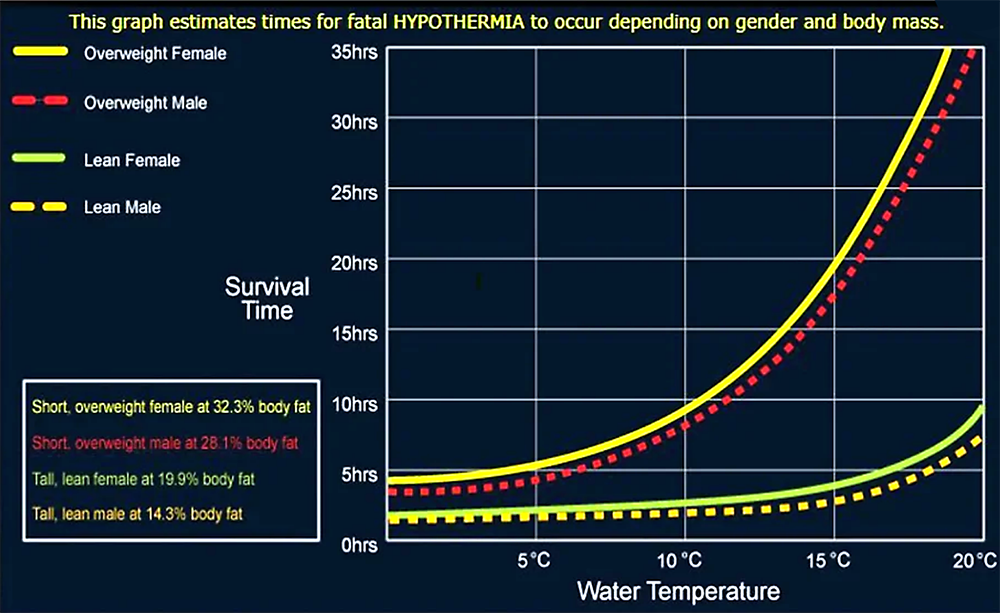

The initial effects of hypothermia involve peripheral muscle cooling, which can impair physical performance, reducing dexterity in the hands and finger followed by the failure of more global movements such as those involved in swimming(2). In fact, even before this point, maximum muscle power falls – by around 3% for every degree C reduction in muscle temperature(3). Continued cold water immersion leads to a progressive reduction in deep body temperature, leading to symptoms of hypothermia, confusion, introversion and disorientation(4). Within 90 minutes or so, death will inevitably occur (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Water temperature, hypothermia and survival*

At water temperatures around 5C, a lean athlete will quickly develop hypothermia, which will become fatal after around 90 minutes maximum. *Based on data from Defence and Civil Institute of Environmental Medicine, Canada(5).

Given these facts, it’s hardly surprising that wetsuit use is preferred by triathletes and open water swimmers when swimming in cooler waters (less than 20C/68F). In fact, when the water temperature is below 16C (61F) wetsuit use is mandatory in official Ironman competitions and permitted in water temperatures of up to 24.5°C (76F). Now consider that in temperate climates such as northern Europe and the more northern regions of the US, open water temperatures in summer rarely exceed 24C, even in summer, which means that in many triathlon and open water swim events, wetsuit use will either be mandatory or preferred. Applying the principle of specificity therefore, it seems to make sense to perform regular swim training through the year while wearing a wetsuit. And because of the limitations of weather and safety, this means performing some training sessions in the pool while wearing a wetsuit.

Wetsuit use and swimming biomechanics

Research shows that when swimming in a wetsuit, swimming biomechanics are subtly altered, which suggests that some wetsuit training is required to adhere to the principle of specificity. In particular, wetsuit use seems to result in slightly differing stroke biomechanics leading to a decreased energy cost of submaximal swimming and an increased distance per stroke(6). Some of this effect arises because by directly increasing buoyancy and holding the body in a more horizontal position, wetsuit use allows more effort to be expended in propulsive movement rather than movement to maintain buoyancy(7). The wetsuit benefit of extra buoyancy also helps to reduce drag, and this is particularly noticeable in amateur and recreational athletes (ie those with less polished swimming technique)(8).

The performance benefits of wetsuit use

Carrying out some regular training in a wetsuit not only improves specificity, there’s good evidence that it enhances swimming performance full stop. To give you some kind of idea of what swimmers can expect, we can turn to some fairly recent research by a team of Spanish and Portuguese scientists who investigated the changes in performance and swimming biomechanics induced by the use of wetsuits vs. ordinary swimsuits in both swimming pool and swimming flume (ie stationary swimming in a moving body of water) conditions(9).

Thirty three swimmers performed two sets of 400m front crawl maximal-efforts in a 25m swimming pool (one with wetsuit and one with an ordinary swimsuit), and their average velocities were calculated. These velocities were then used in two swimming-flume trials, one with each suit. During the swimming flume trials, blood lactate concentration, heart rate, perceived rate of perceived exertion, stroke rate, stroke length and propelling efficiency were evaluated.

The results showed that 400m performance in the swimming pool was 0.07 metres per second faster when using the wetsuit than when using the swimsuit, which led to a reduction of around 6% in 400m times. Maximal heart rates, maximal blood lactate concentration, ratings of exertion, stroke rates, and propelling efficiency were similar when using both swimsuits. The key to the faster times in the wetsuit condition however was that stroke length (distance travelled per stroke) was significantly increased, which also indicated slightly altered stroke biomechanics. When summarizing their data, the authors concluded that wetsuits could be utilized by swimmers during training seasons to improve adaptations.

Triathlon and wetsuit training

More evidence for the benefits of wetsuit training in athletes who compete wearing wetsuits comes from a study on triathletes published last year(10). In this study, 11 national- and international-level triathletes, all who were familiar with wetsuit use, performed seven sets of 200m front crawl at constant predetermined speed on two separate occasions – once with and once without a full wetsuit. The trunk incline and index of coordination (IdC - an index which characterizes coordination patterns by measure of lag time between propulsive phases of each arm) were measured stroke by stroke using video analysis. Stroke, breaths, and kick count, and timing (breathing/kick action per arm-stroke cycle), stroke length and stroke length distance underwater were analyzed using inertial-measurement-unit sensors. Heart rate, rating of perceived exertion and swimming comfort were also monitored during the task.

When a wetsuit was worn, the triathletes displayed a lower trunk incline (ie their body alignment in the water was more horizontal (good for hydrodynamics!) than wearing a normal swimsuit. In addition, the number of strokes, kicks, and breaths required to cover each 200m was lower compared with swimsuit condition. The explanation once again seemed to lie in an increased stroke length and a better stroke index (less lag time between the propulsive phases of the left and right arm strokes), which also explained lower perceived exertion and lower heart rates in the wetsuit condition. Like the study above, the researchers concluded that the use of a wetsuit during training sessions is recommended, not just for better specificity and training adaptations, but also to increase comfort and the positive effects on performance.

Caution is required

At this point, you’re probably assuming that all triathletes and open water swimmers should always train in the pool while wearing a wetsuit. However, some caution is required. Firstly, while wetsuits clearly produce a performance advantage, it’s two-way street. So if you only ever train using a wetsuit, competing in a warm-water event where wetsuit use is not permitted is going to put you at a distinct disadvantage. This is because your training specificity will have honed your muscle motor patterns for wetsuit swimming rather than ordinary swimsuit swimming.

Secondly, making your training physiologically easier might give you a boost while training, but this could be a disadvantage during competition. This is why many swimming coaches advocate the use of devices in training that increase drag, making training harder than the equivalent competition distance – for example swimming parachute and drag suits. Performing some training using these devices can toughen swimmers mentally and physically, and have been shown to enhance performance(11), which is why they are considered a valuable asset in a swimming program. Using a wetsuit during training however produces exactly the opposite effect. And while no studies have ever looked at wetsuit-only trained swimmers, logically and intuitively, this concern makes sense.

The heat is on

When training in a pool, there a third concern relating to wetsuit use and that is body temperature. Wetsuits are designed to retain body heat in order to help swimmers tolerate cold water. However, most indoor swimming pools (where most triathletes will be training over the winter) are heated to 26-29C (79-84F). When swimmers train in warm water wearing wetsuits therefore, a theoretical concern is that too much heat is retained, leading to an undesirable rise in core temperature, drop in performance and harmful physiological effects. But is this concern actually valid?

In a brand new study by Japanese researchers published just two weeks ago, a small number of male and female elite and international level swimmers were assessed to investigate the effects of wetsuit use in pool training on core temperature, subjective perceptions, and swimming performance(12). The swimmers completed two long-distance training swims (10kms) at maximum pace. One trial was carried out wearing a wetsuit and one while wearing a normal swim suit. In both trials, the pool temperature was held at 29C (84F), and in the wetsuit trial, swimmers were told to remove their wetsuit if they could no longer tolerate the heat. The swimmers’ core temperatures were continuously recorded via ingestible temperature sensors and swimming speeds were estimated from every 100m lap time.

What they found

The first finding was that core temperatures rose in both the wetsuit and normal swim suit trial. However, the core temperature rose much more in the wetsuit trial – so much so that all the swimmers had to remove their wetsuit during this trial, with the average maximum tolerance time of wearing the wetsuit being around 46 minutes. In addition to feeling so hot they had to remove wetsuits, the swimmers also swam slower in the wetsuits overall, indicating a gradual decline in performance as time elapsed. They also reported much high ratings of exertion.

Practical advice for triathletes and open water swimmers

If you’re a triathlete who performs in open water, or an open-water swimmer, what’s the best way to integrate wetsuit training into your program? The first thing to say is that thanks to the principle of specificity, some wetsuit training is definitely a good thing. If you want to perform at your best in a wetsuit, the slightly different biomechanics means that you should perform at least some regular training in a wetsuit. Since you will be using a wetsuit in open water conditions, you should try and include open water wetsuit training sessions in your program for maximum specificity.

During the winter months however, some wetsuit sessions in an indoor pool are inevitable for most athletes. In the above study, the researchers concluded that although wearing wetsuits in indoor pools is likely to be an important component of a training program, for the safety of the swimmers, it is recommended that they remove their wetsuit if they feel too hot. When undertaking wetsuit sessions in an indoor pool therefore, sessions should be relatively brief and athletes need to remove wetsuits when they begin to feel warm. Ploughing on feeling tired is not only potentially harmful, training at slower speeds in the water will not develop the motor skills required to swim fast in a wetsuit.

How often should you train in a wetsuit? When training in open water, the answer is course is most or all of the time because it’ll be too cold without! This is especially the case if you know your triathlon or swim event will require wetsuit use. In the winter months when all of your training is in the pool, this is harder to answer because no research has ever investigated this question. You don’t want to be doing all of your training in a wetsuit for the reasons given above. Equally, you’ll need more than just an occasional wetsuit session to hone those skills. Assuming you’re training in the pool three or more times per week, perhaps one or at most two of those sessions should include some wetsuit work. Remember though, as your event approaches wetsuit training will become more important, as your will ability to use it in open waters!

References

1. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007 Mar;39(3):487-93

2. Lancet. 1999;354:626–9

3. Aviation Space Environ Med. 1988;59:738–41

4. Proc R Soc Med. 1973;66:1058–61

5. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1997 May;68(5):441-8

6. J Sci Med Sport 2009, 12:317–322

7. Br J Sports Med 1991, 25:31–33

8. Med SciSports Exerc 1995, 27:580–586

9. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2020 Jan 1;15(1):46-51

10. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2023. Jan 10;18(2):171-179

11. J Strength Cond Res. 2019 Jan;33(1):95-103

12. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2024 Jan 8:1-5

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.