Embracing change: improve your transitions

John Shepherd looks at multi-event transitions, and how you can enhance them to boost your overall performance

Endurance multi-sports, such as triathlon, biathlon and swim-run events require changes in locomotion between the disciplines. These changes also account for elapsed time – time that could affect the overall event result. Indeed, in triathlon, these transitions are deemed to be of sufficient importance that they have become known as the ‘fourth discipline’.Anyone who has ridden a bike for some time and then tried to run (even walk) will have experienced that odd feeling of “why aren’t my legs moving properly?” The simple answer is that the neuromuscular system will have become patterned to one type of movement, and needs time to break into the rhythm of the next. Muscles also tend to become somewhat ‘locked’ into position on the bike - notably the back - and this adds to the difficulty of the transition. It’s for this vary reason that triathletes use ‘brick’ sessions, where they train the cycle to run transition specifically.

So why is it difficult to run after cycling? It’s commonly known that run-step characteristics and ground contact times, for example, are affected when transitioning from cycling to running. The latter, for example, will be slower as the legs literally begin to pick up the pace for the run. However, are these effects long lasting and does the post-cycle run differ biomechanically from runs that aren’t preceded by a cycle?

A team of researchers wanted to delve deeper and look more closely at the process of the transition and see what happened to the running gait(1). They considered differences in athletes’ running patterns and movement precision by comparing a 5000m run completed after cycling with a 5000m run completed with no prior cycling. A running track was used for the run, whilst the participant’s used their own bikes on a turbo trainer. The distances were equivalent to an Olympic/Standard tri (40k cycle, 10k run).

During the run, use was made of three-dimensional acceleration data – in brief accelerometers were attached to the ankles of the participants and measurements made at very high frequencies. Surprisingly perhaps, the results showed that both conditions (ie running after cycling and without prior cycling) led to variable changes in movement precision and running patterns over the initial five minutes. After that, the athletes were able to ‘find their rhythm’.

Change in energy use

If running gait is equally affected with or without a prior cycle ride (at least for the first five minutes), are there more lasting effects - for example, on run technique and energy expenditure? Some research has identified there are(2). The research noted that on the tri run, at least after the initial getting into the rhythm phase, that although biomechanics are not significantly altered, there can be a slight change to a forward lean across the trunk (see figure 1). This – although minor – could be enough to affect running economy (RE).Figure 1: Trunk lean during running

Following a cycle leg, an athlete is likely to exhibit a more pronounced forward lean (right) then when running without a prior cycle leg. This may explain decreased running economy that has been observed.

RE refers to the energy cost of running and is a product of a number of factors, such as leg stiffness and running technique. A runner/triathlete with a superior RE will be a quicker runner/triathlete than one with a lesser level of RE, everything else being equal. It’s therefore recommended that coaches and triathletes carefully analyse running mechanics during a post-cycle run and attempt to make running form as much as possible a mirror image to non-cycle preceded running. In doing so, this they may increase RE and therefore performance. Preparing for the run, with specific on-bike stretches, may also facilitate this (more later).

Technology and transitions

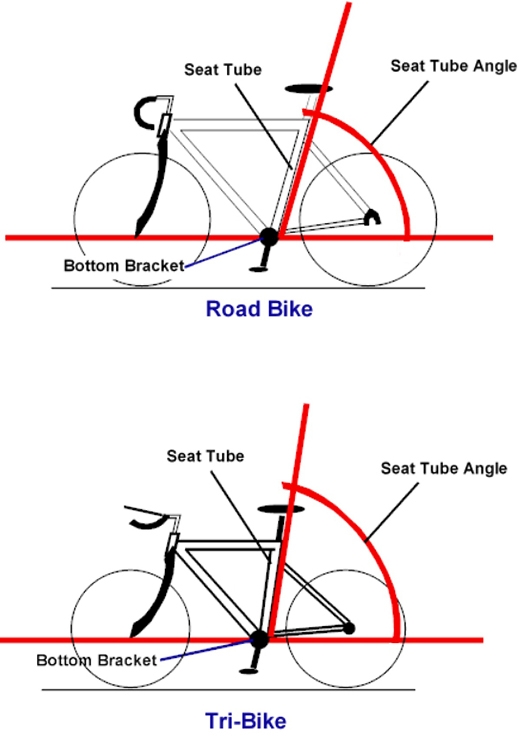

As anyone who has been bitten by the triathlon bug knows, the sport is very much a high-tech one, with flashy carbon-fibre bikes and all manner of computer tech (power meters, activity trackers, heart rate monitoring and so on) being used by weekend warriors. So, can this tech improve transition performance? Let’s consider the most high-tech piece of kit a triathlete will probably have on race-day - their bike. Researchers have investigated at how a bike’s geometry and set-up can benefit the subsequent run(3).The seat tube angle (see figure 2) and hand position were the variables studied by the researchers.Figure 2: Seat tube angle on road and triathlon-specific bikes

Triathlon-specific bikes typically have much steeper (larger) seat tube angles than road bikes. Although this makes for ‘less relaxed’ ride over longer distances, it allows riders to use aerobars in a low position without the need to tilt forward excessively at the pelvis or feeling overstretched while on the bars.

Fourteen triathletes took part in the study and they had their leg muscle activation analysed both when running and cycling. Three hand positions were utilised – aero, on the drops and on the hoods, together with three seat tube angles: 73, 76 and 79 degrees. The triathletes ran at 80%, 90% and 100% of their 10k triathlon race pace. Although adjusting the seat tube angle was found to have no direct effect on muscle kinematics, higher angle increased hip extension when the hands were placed forward on the aerobars. This had a knock-on effect by allowing the hip muscles to work in a way that more closely resembles the movement patterns used during running. The researchers concluded: “These combined changes in muscle kinematics and coordination could potentially contribute to the improved running performance that have been previously observed immediately after cycling on a triathlon-specific bicycle.”

This could be a very relevant factor to experiment with in your training - ie establishing the best cycling position for you or considering the purchase of a tri-specific bike if you do not already have one. Either of these could potentially lead to an improved run performance following the bike leg.

The importance of setting up the bike to minimise differences in movement patterns when transitioning from bike to run is highlighted by further research, which has identified that even elite-level triathletes have their leg muscle activation patterns “disrupted” after a bout of cycling despite many years of training(4). In other words, no matter how elite you are, the change in movement/motor patterns when transitioning from the bike to running will have a disruptive impact.

Can long-term cycling affect the ability to run?

Juggling the demands of a multi-sport endurance activity is no easy task. All competitors will tend to have stronger disciplines. Amateurs and professionals alike will wrestle with the balance between the disciplines, perhaps worrying and wondering whether too much of one will be detrimental to another.Cycling is an activity that’s often the mainstay for many triathletes. Not only does it account for the largest proportion of a triathlon race, it’s also non-load bearing. That makes it a safer option when it comes to maintaining training intensity/volume whilst reducing injury risk. This also explains its popularity as a cross-training option for stand-alone runners. But can too much cycling be detrimental to running over a long period (not just in the immediate period following a triathlon cycle-run transition)?

Researchers compared the running techniques of elite triathletes with evenly matched (in terms of time spent running and distances covered) runners. Electromyography was used to test electrical activity in the leg muscles at controlled running speeds. The researchers found no definitive evidence that running muscle activity is less skilled in elite triathletes than in equally trained runners. In other words, multi-discipline training does not interfere with adaptation of running muscle activity in triathletes. There’s no evidence therefore that cycling mileage is a factor to consider when planning your training, and trying to avoid possible permanent alterations to running biomechanics.

However, further research has shown that that respiratory muscle fatigue induced by prior cycling was maintained, and neither reversed nor worsened, by the successive run(6). This basically means that fatigue accumulates in the breathing muscles of the diaphragm during the cycle leg, which then continues into the run (see figure 3). Pacing judgement is therefore of crucial importance; another implication is that triathletes might benefit from some specific inspiratory muscle training (IMT) using training devices such as PowerBreathe (figure 4) to reduce this effect following the transition into the run leg.

Figure 3: Inspiratory muscle fatigue during cycling

The solid red line represents the position of the diaphragm at the end of exhalation. During inhalation, the diaphragm moves downwards, encroaching on the abdominal cavity, which impedes the movement of the diaphragm, especially in the crouched position, for example when using aerobars. The use of IMT training devices while adopting a crouched cycling position could therefore help reduce IMT on the bike, resulting in less IMT going into the run leg.

Figure 4: PowerBreathe’ IMT device

A number of companies make devices designed to improve your diaphragm strength. Whichever one you try, follow the manufacturer’s instructions to set it to about 50 percent resistance, based on your current breathing strength.

We’ve seen that the cycling to run triathlon transition can have varied effects on subsequent run performance. It would therefore make sense to practise the transition from bike to run by using ‘brick’ sessions. A team of researchers set about seeing whether such specific training can benefit competitive level triathletes(7). One group of six athletes performed regular cycle to run repeats at a high intensity as well as their baseline training. Another group of six simply performed their normal training. Both groups trained for six weeks.

It was discovered that the cycle-run protocol did not have an overall effect on improving cycle and run performance overall. However, the high-intensity cycle to run repeats did improve the ability to transition more quickly during the cycle change and the first 333m thereafter. The researchers concluded that multi-cycle run training sessions may help competitive triathletes to develop greater skill and better physiological adaptations during this critical transition period of the triathlon race. This types of training sessions may help negate (at least in part) the difficulties commonly experiences during the first five minutes of the run leg outlined earlier(1).

Implications for racing

We’ve not yet considered the effects of the swim on the subsequent cycle leg and indeed overall performance. Research that exists indicates that saving energy in the swim by drafting where possible can improve overall finishing times(8,9).As well as practising your cycle to run transition by the use of specific brick sessions, here are some other tips:

- Make sure you make yourself very familiar with the transition situations you will encounter on race day.

- Transition in training using the race gear you will wear on the day – ie mounting your bike on the run after the swim and slipping your feet into already positioned shoes (or closely simulating the race scenario.

- Practice getting your feet out of the cycle-mounted shoes and dismounting on the fly to then put your running shoes on and so forth.

- Prior to dismounting from the bike it’s recommended that you perform some exercises to prepare your back muscles ready for the run. Being tucked over in an aero-type position on your bike may well lead to back spasms at worse and/or a difficulty returning to upright when running. Indeed, this may explain the slight forward lean of the posture noted in the research quoted previously(2). It’s advised that you remain clipped into your pedals, so as you have a more stable platform from which to perform the exercises. Doing a type of ‘cat and calf’ movement, where you first extend the pelvis and spine and then flex them can be a useful release for the spine.

- 45-minute cycle at progressive aerobic effort – 15-min run at progressive aerobic effort.

- Perform a 9-mile (14k) ride and 2.5-mile (4k) run at race speed with simulated race transition in between.

- Repeat above 2-4 times, taking a couple of minutes between sets.

- Cool down with a 15-minute run and 30-minute ride.

Case study: Greg Bennett(10)

Greg Bennett has won six World Cup triathlon titles, as well as being ranked world number one triathlete in 2002 and 2003. He has talked about the swim-bike transition and the fact that many triathletes report feeling dizzy and unbalanced, or experiencing an almost drunk sensation in the transition from swim to bike.

As Greg explains, “Most of us have had this experience, and I used to get it from time to time. I've noticed I got it more often in colder swims and when I had to swim well above myself to stay with the race. There are a number of possibilities as to why this dizziness occurs. One is that you are horizontal for a long period of time. The heart is pumping blood primarily to the upper body. When you stand quickly and try to start running you require the heart to pump blood to the legs quickly. In turn, the blood supply to the head drops. My solution was to focus on kicking the last few minutes of swim, stand a little slower and give my body a chance to feel better. I only started jogging to the bike only once I felt clear headed.

Another possibility is water in your ear. For many this is a cause of losing equilibrium and feeling dizzy. I found the solution for me was to use ear plugs. Low blood sugar can also cause this effect. This can happen to any of us at any time, not just exiting the water and running to your bike. I recommend taking an easily-digestible form of nutrition 15-20 minutes before the swim. Some athletes choose to slip a gel packet under the sleeve of their wetsuit, which offers around 25 grams of carbohydrates and 100 calories (a good ballpark).”

Regarding a fast swim-bike transition, Greg explains that getting the wet suit off and putting socks on quickly is vital. “A good transition is free speed. Lubricate your feet and ankles, lower legs of the wetsuit, the wrist of the wetsuit and the neck using plain old Vaseline or baby oil. Put your hands in a plastic bag to protect them. I also often used to cut the bottom few inches of my wet suit legs (to just below the knees). This makes it come over the feet much more quickly. Lastly, have your socks folded out so you can just insert the toes and then flip over the rest of the sock. Or, don't wear socks at all and just keep feet lubricated. If you must wear socks, try them just for the run.”

References

- Sports Biomech. 2017 Nov 15:1-14. doi: 10.1080/14763141.2017.1391324. [Epub ahead of print]

- Br J Sports Med. 2000 Oct;34(5):384-90

- J Appl Biomech. 2011 Nov;27(4):297-305. Epub 2011 Jul 29

- J Sci Med Sport. 2008 Jul;11(4):371-80. Epub 2007 Apr 26

- Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008 Mar;40(3):557-65. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31815e727a.

- Int J Sports Med. 2003 Jan;24(1):63-70

- Res Q Exerc Sport. 2002 Sep;73(3):289-95

- J Sports Sci. 2009 Aug;27(10):1079-85. doi: 10.1080/02640410903081878

- Br J Sports Med. 2005 Dec;39(12):960-4; discussion 964

- Adapted from Championship Triathlon Training GM Dallan & S Jonas, Human Kinetics 2008

Other articles you may be interested in:

You need to be logged in to continue reading.

Please register for limited access or take a 30-day risk-free trial of Sports Performance Bulletin to experience the full benefits of a subscription. TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.