You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Half marathon training: a proven approach for female masters

How can older recreational runners optimize their training structure to maximize half-marathon performance gains? SPB looks at new research on amateur female masters runners

Although the running boom started with the marathon, it’s actually the half marathon that has become increasingly popular among amateur runners over recent years(1). Indeed, research shows that the number of women and men participating in half marathons increased significantly between 1999 and 2014, and by far more than the growth in full marathon participation, with 123 times more women participating in half marathons than in marathons, 75 times more men registering for half marathons than for marathons and a particularly fast growth in half-marathon running by masters (over 45 year) runners(2).

Half marathon popularity

Why has the growth in half-marathon running outstripped that of full marathon running? A lot of it boils down to practicalities, logistics and the differing physical demands. The fact is that bashing out the high mileages needed to perform well in a marathon can play havoc with work or family obligations, particularly in the case of women with young children(3). Then there are the physical demands of marathon training, which can and often do lead to injury, especially among amateur and recreational runners, and particularly affecting female runners(4). Research also shows that although they often have some prior running experience, many amateur distance runners tend to exceed their upper physical capacity limits (unlike professional athletes) and frequently become overtrained(5). This can lead to poor physiological adaptation or even a deterioration in their physical fitness(6).

Training challenges

Whilst half-marathon training is much more manageable and practical for recreational runners than full marathon training, there are still considerable challenges, particularly when it comes to putting a well balanced training program together. Firstly, most of the half-marathon training plans that have been developed are nearly always adapted from data derived from professional or elite runners(7). For example, many training programs for amateur masters runners tend to focus only on physical performance, with little consideration given to reducing physiological stress. Without this consideration, older runners may be unable to sustain their hobby over a prolonged time period. In addition, data on the key performance-related factors and finish time predictors is hard to come by in amateur/recreational runners(8).

Perhaps unsurprisingly then, while the half marathon as an event for amateurs has become extremely popular, there is no consensus on the best training practices for runners who want to develop their maximum half-marathon potential, while ensuring they can remain healthy and injury free(9). Yes, it’s true that there is a lot of empirical data that runners can use, but very little of it has been derived from scientific studies(10). Also, much of the research that has been carried out has looked at manipulating individual elements of half-marathon training – for example, the effect of adding specific weekly sessions such as intervals, zone training, or of using different recovery and nutrition strategies. There’s actually very little data indeed on overall training program structure, and how it should vary through the year to give the best results.

New research

One of the problems of trying to develop a long-term one-size-fits-all half-marathon training program is that it’s extremely difficult to do precisely because one size does not fit all! However, some brand new research by a team of Romanian scientists provides some great insight into how amateur runners training for a half marathon can successfully develop a long-term (12-month) training program to improve half marathon performance(11). Published in the journal ‘Sports’, this study investigated the effect of a carefully constructed 12-month periodized half-marathon training program on the performance of female amateur masters runners.

What marks this research out was that the women runners were amateur with at least ten years’ of endurance running experience under their belts. And while they were training quite seriously, competing in indoor and outdoor, road and mountain running, they were all amateurs, which meant that were training without coaches and had family commitments and jobs (three physical education teachers, one doctor, one marketing specialist, and one museum curator). They were all also aged 45 or over, thus falling into the masters category.

Periodization matters

With a good training background and participating in competitions, these women were obviously committed runners and had enough knowledge to perform quite well in their chosen events. But the question the researchers wanted to know was whether these runners could perform better if they followed a long-term, periodized training plan that was also adaptable to each runner’s abilities and lifestyle? The concept of periodization was particularly important. Periodization in a program entails continually varying the workload and intensity in repeated cycles to provide the right balance of training stimulus but with optimum recovery and training adaptation(12) – see this article for a more in-depth discussion.

Despite the proven benefits of periodization, research shows that many half marathon runners default to a non-periodized strategy, running a fixed number of kilometres or using fixed intensities throughout a training cycle. In one study on distance runners, researchers discovered that 56% of runners become injured during training or competitions, or engaged in demanding training exceeding 100kms per week, which was often followed by excessive fatigue, making it difficult for the runners to maintain their levels of motivation and diminishing running satisfaction(13). And as mentioned earlier, amateur runners who do attempt to structure their training using the principles of periodization typically follow programs for or adapted from those developed for elite runners, which may be far from ideal(14).

The goal of this new research therefore was to develop, apply, and confirm the efficiency of a staggered (periodized) physical training program over one year (macrocycle) for female master (+45) half marathoners. In particular, the researchers aimed to introduce the elements of experience and good practices of nationally and internationally recognized runners, but in a way that was adapted for amateur runners by manipulating volume and intensity.

What they did

Six female amateur masters runners were recruited and underwent initial medical screening and fitness testing. Following this, the runners were given a 12-month periodized training program to follow. This consisted of 12 mesocycles (one per month) and 52 microcycles (one per week), with each microcycle consisting of 4-5 training sessions per week, depending on the training period. During the year-long program, the runners perform assigned road race events, which were used for monitoring and testing. In these events, the runners were given individual target times, calculated on meaningful gains in running fitness. These events were:

· January - road run 10km

· February - road run 21km

· March - road run 21km, plus testing

· April - road run 21km plus testing

· May – competition in the European Masters Athletics Championships (21km)

The overall structure of this 12-month program was as follows:

· General preparatory period (4th October 2021 to 1st November 2021)

· Specific physical preparation period (1st November 2021 to 30th January 2022)

· Pre-competition period (31st January to 3rd April 2022

· Competition period (4th April to 18th September 2022)

· Transition period (19th to 30th September 2022).

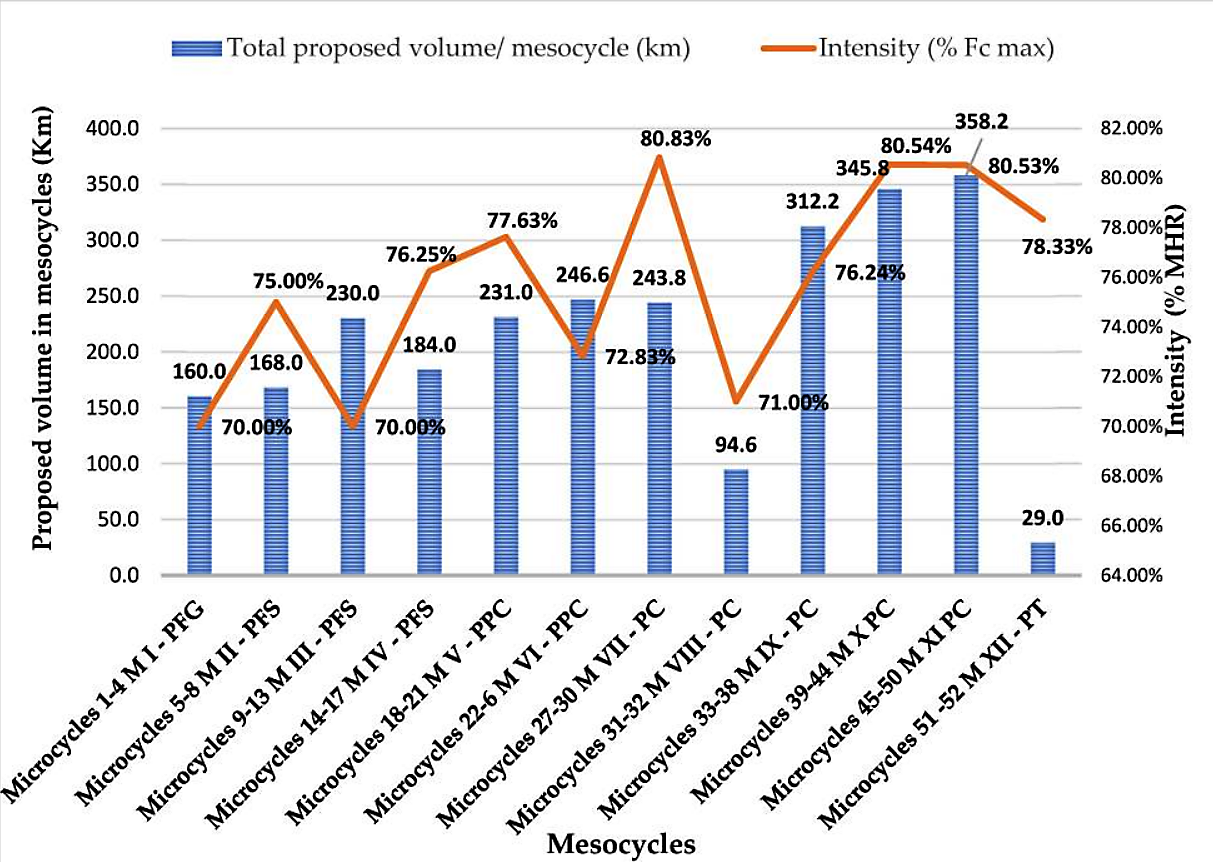

During the general preparation phase, training volume and intensity increased gradually, while in the specific preparation and pre-competition periods, the volume decreased to medium, and intensity increased to an optimal level. In the competition period, the intensity fluctuated from high (submaximal) to optimal for the half marathon event, while volume fluctuated from high to medium, depending on runners’ performances and test results in the assigned events listed above. The periodized volume and intensity variations throughout the year can be seen in figure 1. For a detailed breakdown of the types of training sessions performed in each mesocycle, readers are directed to table 4 of the study.

Figure 1: Periodized 12-month half marathon training plan

Each mesocycle (blue bar) represents the volume (kms run) in a month’s training. Each microcycle = one week’s training. PFG = general preparation; PFS = specific preparation; PCP = pre-competition; PC = competition; PT = transition. Orange plot = average intensity of each mesocycle in terms of % of max heart rate (MHR). Note that apart from the competition period, increases in volume are accompanied by decreases in intensity and vice versa. Totals: training days = 235; training sessions = 235; macrocycles = 1; mesocycles = 12; field tests = 5.

What they found

Although the runners were given this periodized program to follow, they self-trained – ie they were NOT coached, but were simply left to apply it in their own training (as would be the case for most amateur runners). The first finding was that the average total running volume achieved by the runners through the year was around 2,350km – about 90% of the volume proposed in the training program. This was an encouraging result as it meant that by and large, the runners had largely met the volume demands placed on them, without needing to take time off for illness or injury.

Secondly, the training intensity achieved by the runners was around 95% of that prescribed in the program – again, encouraging because it meant that the runners had by and large managed to complete their high-quality sessions. Thirdly and perhaps most importantly, the athletes’ performances in the five tests were either better than or equivalent to the proposed times, which meant that despite having around ten year’s training experience, the athletes were achieving better times than in previous years. This was evidence by the results of the European Masters Athletics Championships held in May 2022 in Italy. In the over-50 category, one runner recorded her personal best time of 01:45:52, while another placed 3rd in the over-45 category. A third runner placed 8th in the over-55 category, another placed 12th in the over-50 category while another placed 17th in the over-45 category.

Using this information

The authors concluded that implementing this 12-month periodized plan can provide amateur runners with a safe and effective training structure, contributing to improved health and athletic performance, and serve as a guideline model for amateur runners who do not have access to coaching. What makes these findings interesting and relevant for amateur runners is that the periodized training plan used was tested on amateur runners who self trained, so is likely to be high transferable to other amateur distance runners without access to coaching.

How can you adapt this program to your own half-marathon training? The first thing you need to do is to identify which event(s) you want to excel in during the next season and work backward from there. In the program above, the initial conditioning began six months before the competitive phase began, and that’s when you should aim to start with this year-long program. For example, if your first event or only is in early July, you need to begin this program in January. In the program above, the runners were averaging around 160-170kms per month, which equates to just under 40kms or 24 miles per week. Peak volume during the competitive phase was around 80kms or 50 miles per week – ie roughly double.

You can use these ratios to adapt the plan to your own mileages and intensities. For example, if you are currently trotting out around 30 miles per week and have been for many months or even years, that’s around 25% more than the mileage shown in the program. Therefore you can adapt the mileages shown by increasing each mesocycle mileage by 25%. When it comes to intensity, the % of maximum heart rate shown in the program will already be personalized to you because you will use your own maximum heart rate. As a rough guide, maximum heart rate is around 220 – your age in years, but ideally, you need to actually check this with a maximal test. In terms of how to break down your 4-5 training sessions per week, you can use table 4 of the study as mentioned above to help flesh out your sessions!

References

1. Springerplus. 2016;5:76. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-1704-9

2. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:8289

3. J. Physiol. 2008;586:55–63

4. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2021;31:e277–e286

5. Bompa T.O., Haff G.G. Periodization: Theory and Methodology of Training. 5th ed. Human Kinetics; Harrogate, UK: 2009

6. Sports Med. 2000;30:79–87. Sports Med. 2000;30:145–154

7. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2011;6:273–293

8. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2016;8:26

9. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2021;6:30

10. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018;15:2262

11. Sports (Basel). 2024 Sep; 12(9): 256

12. Bompa T.O. Periodization Training: Theory and Methodology. 4th ed. Human Kinetics; Harrogate, UK: 1999. p. 414

13. Discobolul—Phys. Educ. Sport Kinetotherapy J. 2021;60:280–293

14. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:5649

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.