You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Half-time: a good time to ‘re-warm up’?

Pre-match warm ups are a common practice for players, but can and should a brief re-warm up be part of the half-time routine too?

Why do athletes need warm ups prior to competition? Without delving too deeply into the physiology, the human body is not ideally suited for sudden hard efforts from the rested state. Muscles that are cold are also more inelastic, increasing the amount of internal friction (and effort) required for muscle movement. They also lack an optimum flow of oxygenated blood, which leads to higher concentrations of muscle-fatiguing lactate than would occur when the same hard effort is performed from an active state. Likewise, joint structures supporting the working muscles are stiffer and require more effort to move through their natural range of movement when they’re cold, making movement less efficient and the ligaments supporting these cold joints more prone to damage or tears.The nature of warm ups

Over the past three decades, a large body of research has accumulated on the benefits of pre-exercise warm ups for athletes, both in terms of improved performance (through more efficient movement) and reduced risk of injury. In particular, much of this has focused on warm-up structure – ie what constitutes an ideal warm up and how that might vary according the nature of the sport that is about to be performed. You can find a much more detailed discussion of what constitutes the ideal warm-up composition in a two-part article – follow these links for part one and part two.However, although science has established that a pre-exercise warm up is a very worthwhile procedure prior to sport, team sport players where matches are in two halves face something of a dilemma; while this limited period of time provides for rest and recovery, the opportunity for refuelling, and of course the all-important encouragement and discussion about tactics from the coach or team manager, it also results in a steady cool down, which is not ideal for when players return onto the pitch. Performing a re-warm up during half time is of course an option, but if nearly 50% of the half-time period is spent on a re-warm up, the other necessary functions of half time can be severely curtailed. Skipping a re-warm up however is not ideal because studies show that passive rest during half time results in 1.1 degrees C and 2.0 degrees C reductions in core and muscle temperatures respectively(1), and also that these reductions results in performance reductions, particularly where high-intensity running is required(2), and greater injury risk(3) during the second half of play. However, the good news for team players is that new research by Japanese scientists suggests there may be a way for match players to have their half-time cake and eat it.

The research

Published earlier this month in the journal Frontiers in Physiology and titled ‘A 1-Minute Re-warm Up at High-Intensity Improves Sprint Performance During the Loughborough Intermittent Shuttle Test’, the goal of the researchers was to investigate whether a time-efficient and feasible re-warm up protocol could be successfully used during half time. Therefore, instead of using a somewhat impractical 3-7 minute re-warm up protocol (shown to be successful in previous studies(4)), this study looked at the effects of a 1-minute re-warm up performed at high-intensity on the subsequent performance and physiological responses during the Loughborough Intermittent Shuttle Test (LIST). The LIST is a measure of high-intensity running performance interspersed with less intense recovery walking/jogging/running, and therefore a good way of establishing whether this 1-minute re-warm up would be useful at mitigating the running performance reductions often observed after half time.In two separate trials, the subjects, 12 male amateur team sports players with backgrounds in soccer, basketball, handball, and lacrosse, performed a simulated match of two halves separated by a 15-min rest (representing half time). Each half comprised of repeated LIST exercise cycles (three in total per half) designed to replicate the kind of activity typical in match play. Each cycle consisted of 3 × 20m reps of walking, 1 × 20m maximal sprint, 3 × 20m reps of jogging, and 3 × 20m reps of running. The difference between the two trials was that during the half time break, the participants varied their protocols:

- In the control trial, the subjects simply rested seated for the whole 15 minutes of the half time break.

- In the ‘re-warm up’ trial, the subjects sat passively for 14 minutes, but then performed a re-warm up procedure consisting of running for one minute at 90% of the maximal oxygen uptake (hard) for the final minute of the half time break.

The findings

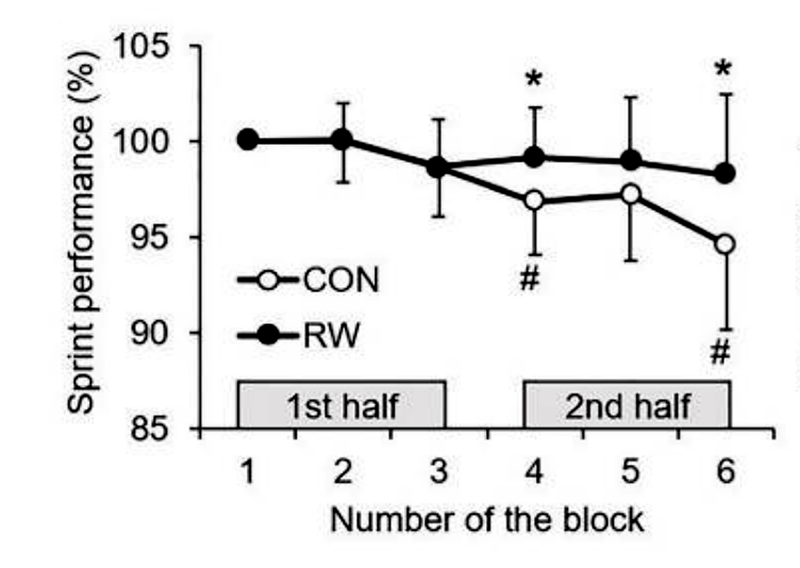

The key findings were as follows:- Compared to completely passive rest, the 1-minute re-warm up during the last minute of half time prevented reductions in sprint performance in the fourth and sixth cycles of the LIST – ie during the first 15 minutes of the second half and the final 15 minutes of the second half - by 2.4% and 3.6% respectively.

- The re-warm prevented the reduction in core temperature that occurred during the passive half time.

- Compared to the control condition, the re-warm up decreased the amplitude of electrical stimulation required to produce maximal voluntary contraction in the players’ leg muscles (hamstrings) by 9%, suggesting an increased neuromuscular efficiency.

- Although the players were able to work harder in the second half after a re-warm up, they reported on average slightly lower levels of perceived fatigue.

Figure 1: Average sprint performance with a passive half time vs. one with a re-warm up

Sprint performance improved when a re-warm up (RW) was performed compared to a completely passive half time. Note that the biggest improvements were observed towards the end of the second half.

Practical implications

This study provides solid evidence that performing a re-warm up consisting of 1-minute high-intensity running in the final minute of a 15-minute half time break may significantly prevent the reductions in sprint performance that are typically observed in players on the field during the second halves of matches. Performing a re-warm up in the final minute of half time therefore seems like a no-brainer; In soccer for example, it is known that the ability to perform high-intensity exercise can affect match outcomes(5), and the most frequent action during goal situations in professional soccer matches is straight sprinting(6). And while this study didn’t assess changes in skill or agility, there’s no reason to believe that any gain in sprint performance would occur at the expense of other physical attributes; indeed, the fact that high-intensity sprinting performance was improved, neuromuscular activity was increased and average perceived fatigued declined somewhat, it’s likely that attributes such as agility might also be improved.References

- Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2004 Jun; 14(3):156-62

- Sports Med. 2015 Mar; 45(3):353-64

- Br J Sports Med. 2002 Oct; 36(5):354-9

- J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2018 Jan-Feb; 58(1-2):135-149

- Biol Sport. 2018 Jun; 35(2):197-203

- J Sports Sci. 2012; 30(7):625-31

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.