Pace yourself to a PB: why a fast start could be your best option

Rick Lovett explores the most successful pacing strategies used by elite runners, looks at the benefits of a ‘fast start’ pacing strategy and provides examples of a fast start pacing strategy in action

When I was young and chasing personal bests at my favorite distances, my strategy was simple. I’d go out for the first half of the race at PB pace – and then try to speed up in the second half. If it worked, that was great. If not, I figured that a PB wasn’t to be found that day, no matter what I did! Later, I wrote two books with Alberto Salazar – ex world record holder for the marathon and now Mo Farah’s coach - who told me the best strategy for his marathon events, was similar: go out conservatively for the first half, and then speed up. As he put it, “For the first half of the marathon, your body is still warming up.”Warming up the pace

The ‘still-warming-up’ concept probably works best for the marathon, where pre-race warm-ups are minimal and pace is relatively slow. But the world’s best splits at shorter distances seem to validate Salazar’s wisdom. According to posts on letsrun.com, when Kenenisa Bekele ran the still-standing 5,000-metres world record (12mins:37.35secs) in 2004, his kilometer splits were as follows 2:33.2, 2:32.2, 2:31.8, 2:30.5, 2:29.4—a remarkably steady speed-up (see figure 1). When he again set a world record in the 10,000 metres, five years later (26mins:17.53secs), his splits were 2:39.85, 2:35.78, 2:37.59, 2:36.96, 2:39.21, 2:35.47, 2:39.32, 2:40.67, 2:40.46, 2:32.44 (figure 2). These were a bit more variable than for the 5000m, but also showed a different strategy: he ran the first six kilometers at very close to his average pace, and then slowed slightly in the next three kilometres as he gathered energy for a fast finish.FIGURE 1: KENENISA BEKELE’S 5,000-METRE PACING STRATEGY

FIGURE 2: KENENISA BEKELE’S 10,000-METRE PACING STRATEGY

Elite studies

Bekele and Salazar are only two runners, but the scientific literature contains a number of studies that have looked at other elite competitors. In 2006, for example, a team of South African researchers examined lap times in 92 world-record performances at 800m, 5000m, and 10000m, from 1912 to 2004Int. J. Sports Phys. & Performance 2006. 1(3), 233-245. They found that the 800-meter runners almost always started fast, typically running the first lap 2.4 seconds (4.6 percent) faster than the second one (positive split). Only twice did someone manage to set an 800m world record on a negative split. However, at distances of 5,000 and 10,000 metres, record-setters tended to go out fast in the first kilometer, slow a bit in the middle, then speed back up in the final kilometer—not what Bekele did in either of his races.Another study looked at national and world-championship-level rowers racing over a distance of 2,000m, which at the elite level takes about 6 to 8 minutes (slightly less than a 3,000m run on the track)J. Sports Med 2005. 39:39-42. Researchers tabulated the 500m splits for nearly 1,000 racers, which included both men and women, as well as various-sized crews. The results showed that rowers at this level went out at 103.3% of average speed for the first 500 meters, fell off to 99.0% in the second 500m and 98.3% in the third, then sped back up to 99.7% in the fourth (see figure 3). This is remarkably similar to what the South African study found for 5,000 and 10,000-meter runners.

Yet another study examined the pacing strategies of competitors in the 2009 IAAF Women’s Marathon Championship, comparing their speeds through the race to their average paces in their PB racesJ Sports Phys. & Performance 2013. 8(3), 279-285. The top quartile (25%) of finishers pretty much followed Salazar’s advice, although in a slightly more complex pattern. Compared to their overall PB paces, these women ran the first 10 kilometers slower than any of the other groups. Then they sped up, and sped up again after 35kms, finishing faster than any other group. Runners in the other three quartiles started comparatively faster but finished slower, indicating that even World-Championship competitors can be swept up in the moment and rediscover that the marathon is an unforgiving event!

FIGURE 3: 2000M RACE SPLITS FOR ROWERS (EXPRESSED AS % OF AVERAGE SPEED)J. Sports Med 2005. 39:39-42

Free energy

These three studies basically show what coaches have long preached; at the marathon distance, you absolutely must have a reasonable assessment of your target pace, or you will pay a big price late in the race. In shorter races, you can go out a bit faster, but you need to tame it quickly and ‘settle in’ to something close to your target pace.Part of what may be involved in shorter races is what I once heard described as ‘free’ energy. Although this term is not used in the scientific literature, the concept is simple. The body has several energy systems that kick into gear in different-length races (see figure 4). Distance runners tend to think mostly in terms of the so-called aerobic energy system, of the so-called aerobic energy system, although the anaerobic system is useful for finishing kicks, and also comes into play in races like the 800m and 1500m. But there are two other systems more better known to sprinters: stored ATP (adenosine triphosphate, the molecule the body uses to store metabolic energy for all purposes) and stored creatine phosphate (another high-energy molecule). Standing at the start, your body has recharged both of these to their maximum levels—Nature’s gift for a fast start. They’ll help carry you for somewhere between 10 and 30 seconds, depending on what study you read. That’s not far, but it’s 10 to 30 seconds in which you can surge, with limited need to pay the piper later on. Most likely, this is why the best 800m runners generally start fast. In longer track races, it also helps runners get to the inside rail quickly, which in world-record attempts is important.

Figure 4: Schematic representation of contribution over time of the body’s energy systems

Treadmills & stationary bicycles So far, the studies we’ve discussed all deal with elite runners, in front-of-the-pack conditions. However, there’s no reason to be certain that what works there also works for the rest of us. In an effort to deal with this, another British team had seven good but not elite male cyclists perform 10-mile time trials on a cycling ergometerErgonomics 2010. 43(10), 1449-1460. The experiment was primarily designed to test the effect of simulated headwinds and tailwinds, but in the process, it found that the best time-trial results came from a constant pacing strategy, as measured by power output.

Another study, from Brazil, had 24 men run 10K time trials on a treadmill, dividing them into groups based on performanceEur. J. Appl. Physiol 2010. 108: 1045-53. The slowest group averaged about 41 minutes; the fastest was somewhere around 32 minutes. What they found was that the fast runners surged in the first 400m then gradually slowed, until they reached 2 km. They then ran a steady pace until the final 400m when they kicked again. The slower runners also started fast, but steadily lost pace all the way to the last 400m, when they too managed a kick. Once again, the basic lesson from these two studies is what you may have already heard or experienced yourself - if you start too fast, you’re going to die! The best results come from fairly even efforts (with appropriate adjustments for terrain and wind). Negative splits are fun but positive splits are death marches.

Game changer

But there’s another study, and it’s potentially a game changer for runners racing over short distances. It comes from a team led by Amy Gosztyla (then of the University of New Hampshire) and Robert Kenefick of the US Army Research Institute of Environmental MedicineJ. Strength Cond. Res. 2006. 20(4), 882–886. The researchers began by recruiting eleven moderately trained’ female distance runners (average 5km time around 21 minutes). They then put these women on treadmills and, over the course of several weeks, had them run five separate 5km trials on five separate occasions.The first two trials, the runners picked their own pace and simply ran as fast as they could to determine their baseline pace. But for the next three attempts, the researchers set the pace for the first mile (1.63 kilometers). The sequence of these time trials varied, but on one occasion, the first mile was set at the average pace from the runner’s faster baseline time trial. On another, it was 3% percent faster and on another, it was 6% faster. After the first mile, the runners were then turned loose to run whatever paces they picked.

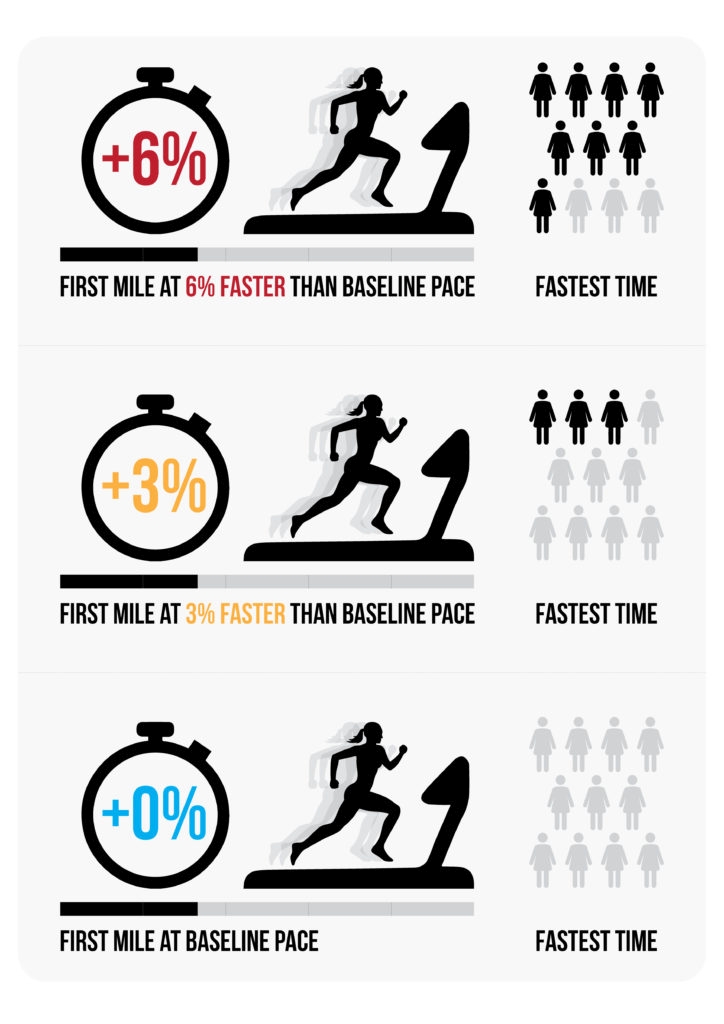

The results were startling. Eight of the eleven runners ran their fastest times after the super-quick first mile at 6% faster pace. The other three did so when they started 3% faster than baseline. Nobody scored their best result by starting out at baseline pace (see figure 5). The researchers concluded that in order to optimise 5km performance, runners should start the initial 1.63 km of a 5km race at paces 3-6% greater than their current average race pace.

Figure 5: Super-fast race start and PBs

For a 21-minute 5km runner, running the first mile 6% faster means doing the first one third of the race at a whopping 15 seconds per km faster than your pace history says you can sustain! “That could cause oxygen debt that would make the [rest of the] race seem really tough,” says Bob Williams, a Portland, Oregon, coach who has worked with everyone from average athletes to US national champions. Paul Greer, coach of the San Diego Track Club, agrees. “When coaches tell their athletes not to go out too fast, this is exactly what they are advising them not to do.”

So what’s going on in this study? Two-time U.S. Olympic Team Trials marathon competitor Amanda Rice (see case study) thinks a lot of it is psychological. She calls it ‘throwing the spaghetti at the wall’. In cooking lore, the way to determine if spaghetti is perfectly cooked is to throw it at a wall and see if it sticks. If it does, it’s al dente. If not, it isn’t.

Modern cooking websites dismiss this as myth, but the point is that sometimes runners need to throw caution to the winds. I myself discovered this when I ran my lifetime mile PB. I’d joined my training group planning a normal track workout. But Henry Rono, one of the first great African runners, happened to be in town and joined us. At the time he held the world records for the 10,000m, 5,000m, 3,000m steeplechase, and 3,000m flat! Intimidated barely begins to describe how I felt. If Rono turned on the jets, I was in serious danger of being lapped in a four-lap race.

My response was to run the first three laps like a frightened rabbit. For 1200 meters, all I wanted was not to get lapped. Only then did I realise that I was well ahead of my PB mile pace, though I no longer had the brainpower to figure out by how much. I struggled through the last lap - desperate now simply to hold on - and lowered my mile personal best by a whopping seven seconds.

Later, I learned that I was not the only one in my club to set a PB that night. Sometimes, if you throw yourself out there, especially in a shorter race where the consequences of overcommitting aren’t as dire as in a marathon, sheer determination and the desire not to embarrass yourself may get you something you’d normally have seen as impossible.

Knowing you are being watched may also contribute to this effect. The 5km treadmill runners in the study above knew their performances were being monitored. So when they were sent out at what looked like a suicidal pace, they would have felt a powerful motivation to hang on — more powerful, possibly, than most of us feel in an actual race.

Rice compares it to the time when she decided to run a 1-mile time trial, in an effort to see if she could lower her PB to under 5 minutes (she ran 4:57), even though the mile wasn’t her distance. “I literally thought I was going to die,” she says. But she also knew that not only her own coach, but two other elite coaches were timing her. “There were three watches on me. I felt ‘Oh my God, you better give it your all.’ I think having an audience is crucial, because it takes someone with a lot of mental strength to do it all by themselves.” What does this mean? Sometimes the science doesn’t matter. Sometimes you just have to run, because breakthroughs occur by taking chances. And if the breakthrough doesn’t occur? Sometimes the best lessons come from race plans that don’t pan out.

CASE STUDY: Amanda Rice

Amanda Rice is a dentist from Portland, Oregon who didn’t take up serious competition until her last 15 months of dental school. One of her strongest racing memories is her one and only indoor 3,000m race, which she ran on a 307-metre track near the end of her first year of competition.“My experience was the 5K, and I was trying to figure out the pacing,” she says. “I knew I was trained and competitive, so I took it as ‘run as fast as you can and try to hang on’!” She pushed hard in the first lap in order not to get boxed then settled into a fairly even pace until two laps before the end, when she heard someone yell, “One lap to go!” She sprinted to the lead, crossed the line, stopped - and watched her rivals speed by! Shocked and mortified, she dashed back into action and managed another lap nearly as fast as the one in which she’d thought she won, finishing in 9mins:54.57secs.

She later estimated she’d lost about six seconds standing around at the finish, but the experience of having to sprint an extra lap at the end of an already tough race taught her how hard she could run if needed. In the ensuing months, she won Portland’s most prestigious road race, ran a 2:38:57 marathon, a 1:14:36 half-marathon, and was top American in the Army Ten-Miler, which is a 20,000-runner race in Washington, D.C. “I keep going back to the expression ‘throwing the spaghetti to the wall’ she says. “Sometimes you don’t realise what you can do until you’ve accidentally cornered yourself into finding out.”

You need to be logged in to continue reading.

Please register for limited access or take a 30-day risk-free trial of Sports Performance Bulletin to experience the full benefits of a subscription. TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.