Peaking: the art of planning and tapering

The traditional annual cycle of training and racing has been turned on its head by lockdown. How can athletes returning to competition ensure they still peak at the right time to maximize performance?

The traditional annual cycle of training and racing has been turned on its head by lockdown. How can athletes returning to competition ensure they still peak at the right time to maximize performance?

The natural world is governed by rhythms and change and one of the most fundamental rhythms of all is that of activity and rest. After activity, we eventually need rest and recuperation in order to effectively repeat that activity. The same is true for athletic endeavor. If you want to reach a new peak, either in training or in competition, you need to understand that your body works best when you allow it to ebb and flow with its natural activity/rest rhythm. You can’t perform at your best all the time, but you can be at your best when it really counts…

Rest, recovery and adaptation

What is peaking and how do you accomplish it to lift your performance just when you need to? In a nutshell, peaking is all about manipulating your training program, so that you can be in the best possible physical condition for an important event. The art of peaking acknowledges the fact that the human body is not merely a machine that requires nothing more than topping up with fuel and water to function. It’s based instead on the understanding that your body is a complex living organism, governed by rhythms and which is constantly regenerating itself and adapting to the stresses and physical demands placed on it.

When you train, you create an ‘adaptation stimulus’, after which your body undergoes repair, growth and metabolic adjustments so that the next time you train that way, you can handle the training load better – i.e. you have ‘adapted’. However, creating the training stimulus is only part of the adaptation process. The other part is rest. Without sufficient and proper rest, your body can’t adapt efficiently to training. Too much training, and not only feel stale, you risk become deeply fatigued and overtrained. Too much rest on the other hand and you’ll begin to lose fitness and become deconditioned. When you peak, you aim to maximize adaptation and recovery for a specific event by increasing your rest time and reducing your training volume, while ensuring that what training you are doing is sufficient to maintain your maximum fitness level.

Adaptation – slowly does it

An often overlooked fact by athletes is that the physiological benefits of a training session performed on day one will not become fully apparent until quite a few days later. During this time period (also known as recovery!), adaptation takes place, where muscles are refuelled and rehydrated, damaged muscle fibres are repaired and built stronger, and signalling molecules produced during training increases the expression of various genes within muscle cells – genes that alter the biochemistry of the muscle cells so that they can respond to the physical demands placed upon them more efficiently. This takes time with the length of time varying according to an athlete’s biochemical individuality, age, fitness level, nutrition during recovery, and quality of sleep and rest during a recovery period.

You could of course ensure total recovery by taking a month off before your race, but that would entail significant fitness losses. However, research shows that there are no significant losses in muscular or aerobic fitness until around 5-6 days after cessation of training. At this point, muscles begin to become less efficient at ‘soaking up’ glucose (the body’s premium fuel for exercise) from the bloodstream and also become less efficient at coping with lactate accumulation during sustained efforts(1-3). The upshot is that you will need at least five days of rest and recovery to perform at your peak before an event.

However, if your training load has been very high – for example, preparing for an ultramarathon or triathlon – it can take longer for muscles to become ‘deeply’ rested. Indeed, one recent study showed that ultra-runners completing an ultra-mountain marathon required 2-4 weeks for all the indices of recovery to return to normal(4). If it takes more than one week to allow muscles to undergo deep recovery yet we know that aerobic fitness losses can begin within 5-6 days, this begs the question ‘how can an athlete arrive at the start line deeply rested but fully aerobically fit’? The answer is tapering.

The optimal taper

When preparing for a major competition, athletes tend to reduce their training load for a variable period of time, usually around two weeks. This technique, known as ‘tapering’, can have a major influence on the athlete’s performance, leading to a gain in performance of around 3% (and possibly up to 6%) compared to no taper(5). However, while training load is reduced significantly, the training INTENSITY is not. Also, training frequency, while undergoing some reduction, is not reduced markedly. A number of studies on the best way for athletes to taper have been carried out over the past seventeen years, and their findings can be summarized as follows(6-9):

- #Athletes need to have a good endurance base and ‘training volume in the bank’ to fully benefit from tapering.

- #The average taper period should be around two weeks but may be as little as four days (for short events) and up to 28 days for long events (eg ultra racing).

- #Training frequency should be maintained or reduced slightly but no more than by around 20%.

- #Training volume should be reduced by 40-90% (yes, 90% reduction!) during the taper, with the biggest reductions in volumes coming in the final week.

- #The INTENSITY of the training must be maintained. With lower training volumes, this can be achieved for example by increasing the proportion of interval training.

Despite the science being unequivocal on tapering benefits, many athletes continue to train hard right up to a few days before an event or competition then fail to reach their potential because they’re competing without being 100% recovered from their previous training sessions. In short, training hard until a couple days before your event will mean your physiological peak will likely occur around 10 days after the event has taken place!

The long and the short of peaking

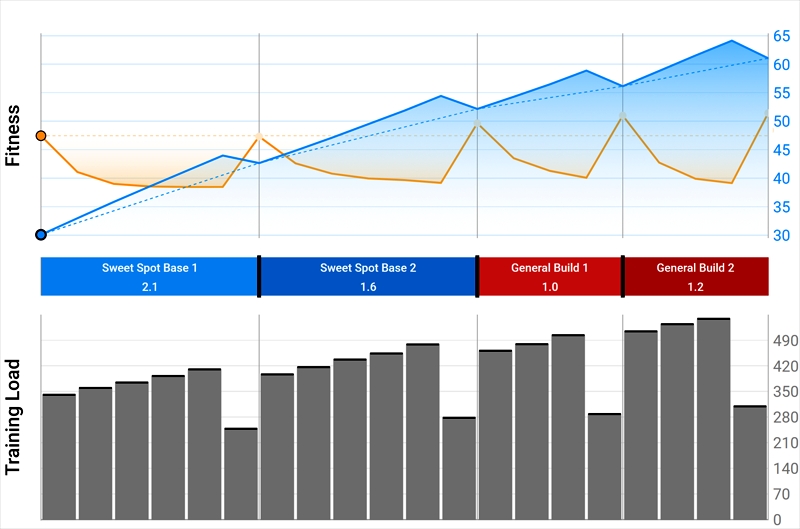

A long-term training program should also take into account the need to intersperse harder periods of training with easier periods, while the overall intensity is racked up to produce a peak fitness around about the time of the most important event(s) of the season. It should also include periods of complete or active rest. This concept is known as ‘periodisation’. For a full discussion on the concept and practice of periodization. Peaking then is really just the final stage of this long-term preparation based on systematic year round periodized pattern of training. The higher the level of competition, the more elaborate the periodized training needs to be. Having said that, the final and critical phase of maximizing adaptation and recovery for a specific event - by increasing rest time and reducing training volume - is fairly similar for both elite and recreational athletes.

Tapering your tapering

Simple logic suggests that tapering for a marathon is going to be a very different kettle of fish from a 5000m. In a nutshell, the longer your event, the longer your taper period needs to be. The reason is simple – longer distance events require larger training volumes, which in turn means more time is required in the tapering period for full recovery and adaptation to occur. As we mentioned above, research suggest that up to four weeks may be required to fully taper down for an ultra event or after a very heavy period of training(4). This is particularly true in marathon and ultra-marathon running/training; the impacts involved in running exact a heavy toll on muscle and connective tissue, which subsequently needs more time to recover(10). Other endurance events such as swimming, rowing and cycling are less demanding in this respect and will therefore require less extensive tapering. A word of caution however; while intensity is the key to maintaining aerobic fitness, as you cut your training right down, this high-quality intensity work should already have been incorporated into your training program well before the tapering period begins. If you suddenly introduce high intensity training to unaccustomed muscles, you’ll get very sore, even if you have slashed your overall training volume.

GENERAL PEAKING PRINCIPLES

- *Plan out your training for the year ahead and around your long-term goals- remember that to successfully apply peaking and tapering principles, you need a solid aerobic foundation in place.

- *As a general rule of thumb, you can gradually cut your training volume down to just one fifth of normal without any loss in fitness providing you retain all your quality high-intensity work

- *The longer your event and higher your normal training volume, the longer your taper period needs to be.

- *For short events under 15 minutes duration, the consensus is that you can allow just 7-10 days for tapering; for medium duration events up to an hour, 10-14 days is recommended. Longer than this and you’re looking at 2-3 weeks for full adaptation and recovery.

- *High impact sports that produce more ‘training-damaged’ muscle and connective tissue such as running, require longer tapering periods than do lower impact sports such as swimming and cycling.

References

- (Int J Sports Med. 2012 Apr;33(4):253-7.)

- J Strength Cond Res. 2012 Aug;26(8):2087-95)

- J Appl Physiol. 1986. 60: 95-99

- Eur J Sport Sci. 2019 Aug;19(7):876-884

- Int J Sports Med . 1998 Oct;19(7):439-46

- Eur J Sport Sci. 2020 Mar 14;1-12

- Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003 Jul;35(7):1182-7

- Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010 Oct;20 Suppl 2:24-31

- Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007 Aug;39(8):1358-65.

- Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2014 Mar;39(3):340-4

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.