You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Solo or group sessions for the best training outcomes?

Andrew Sheaff looks at recent research on the relationship between emotional states and training loads, and how athletes can leverage it to improve their training outcomes

As technology and training methodology advance, we learn more and more about what is happening during training, and we become more skilled at managing it. Over the years, a key concept in training monitoring has emerged, which is the distinction between internal load and external load. The internal load reflects the stress the body is experiencing during activity. Examples of measures of internal load are heart rate and lactate values which reflect the physiological cost of movement. External load reflects what the athlete actually does. Speed and distance are both measures of external load.

While there is a clear relationship between external load and internal load in that they will generally move in the same direction, and over time, it’s become clear that these two measurements do not always sync up. As an example, the speed a runner will be able to sustain in the heat will be much slower than in cooler weather, even if the heart rate is the same. Gradually, an appreciation of the nuance of these relationships has grown.

The group effect

Training is sometimes performed both in a group setting and sometimes in an individual setting for various reasons. At first glance, it would appear that these two topics (training loads and training setting) are unrelated. However, most athletes will tell you that they prefer training in groups, particularly during challenging training sessions. Why is that the case? Could it be that they intuitively understand that they’re able to perform at the same level with less effort when training in a group? If that’s true, it’s certainly worth knowing if internal and external loads are different based upon whether athletes are performing individually or collectively, not least because failing to appreciate the differences could lead to load management errors.

While internal measures of load have often focused on physiological measures such as heart rates and lactate values (as mentioned earlier), sports scientists now believe that ‘psychophysiological’ measurements are relevant as well. How hard athletes feel they are working, as well as the emotional impact of training sessions is important. While these measurements may not reflect physiological loading, they DO reflect an impact on overall stress levels that is real and significant. There are a lot of interesting ideas here, so let’s tie everything together with a study that looks the physiological and psychophysiological impact of training both individually and collectively.

The research

A team of international researchers recruited 16 elite Spanish middle distance runners, who were all competing at national and international level(1). On two separate occasions, the runners performed the same high-intensity training session, which consisted of 4 x repetitions of 500-meters with a 3-minute passive recovery between repetitions. On one occasion, the athletes performed the repetitions individually. On a separate occasion, the athletes performed the same exact session except it was performed in a group setting.

As runners often perform training both individuals and as part of a group, the purpose of the study was to compare the impact of performing that high intensity training session individually and collectively to see if there were any differences in performance, physiological response, or psychological response. To determine whether any differences existed, several tests were performed through the training session.

Since the objective of these sessions was to run fast, performance times were recorded for every repetition in order to acquire a critical measure of external load. This allowed the researchers to determine if training within a group influenced how fast the runners were able to run. As these were high intensity runs, lactate values were measured to gauge the degree of metabolic activation.

While training is typically focused on performance measures and physiological measures, psychological measures are also critical as well and provide valuable information about the session that is independent of performance physiology. Therefore, the researchers also measured the rating of perceive exertion, or RPE, which indicates how hard the athletes felt they are working.

The researchers also measured something called the ‘core affect-valence’. This is an assessment of their general emotional state. Positive numbers imply an overall positive effect or emotional state, whereas negative values indicate a negative emotional state. This measurement provided insight into the emotional impact of the two training sessions. With these various measures, the researchers were able to gain a comprehensive picture of training collectively versus individually.

What they found

After all the data was analyzed, some very interesting results emerged. When it came to performance, there were no differences between the groups. Unsurprisingly, both groups trended toward running slower with subsequent repetitions. This effect appears to be more emphasized in the individual repetitions, although it was not significantly different. When it comes to performance therefore, it appears that there’s no difference between running individually and collectively.

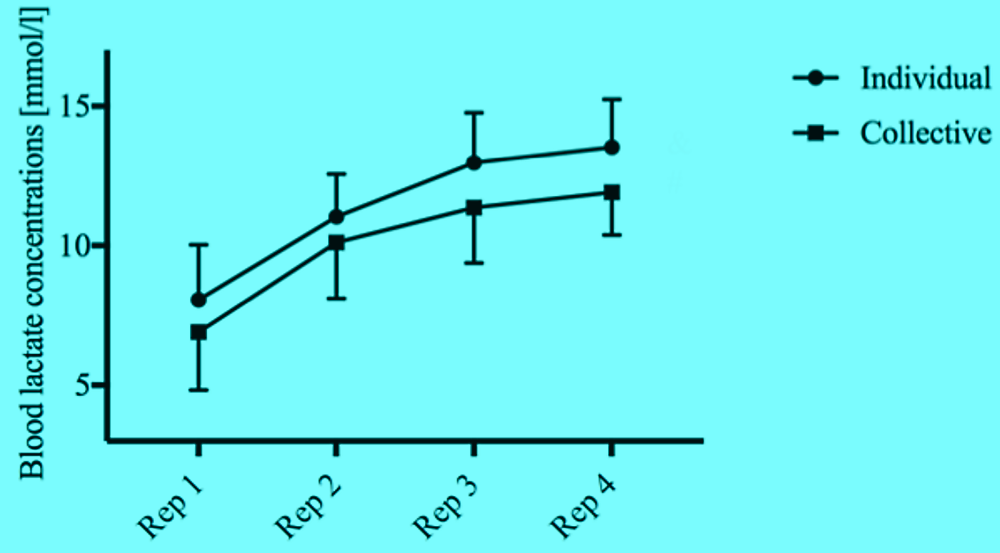

However, when it comes to the blood lactate values, the results were much more interesting. For both groups, each repetition led to higher and higher post run lactate values (to be expected). What was not expected however was that the lactate values were significantly lower after each repetition while running collectively versus individually (see figure 1). Remember, the runners were running at the same speed!

Figure 1: Blood lactate in individual vs. group settings

For rating of perceived exertion, the same pattern was seen. RPE climbed after each repetition in both groups. However, it was lower at every step in the runs that were performed collectively. Not only was the physiological cost of the running reps lower during group training, the subjects also felt like the runs were easier and they weren’t exerting as much effort. The physiological differences were manifested in psychological differences.

Perhaps most interesting of all was the finding related to core affect- valance. While both groups began the workout with a positive valence, the collective group had a significantly more positive affect. And that affect stayed positive throughout the whole session, with the athletes ending the session still feeling positive. In contrast, when the runs were performed individually, affect quickly became negative and the session ended that way. Again, the presence of others impacted the outcomes of the sessions, this time with the athletes’ emotional state differing.

Practical applications for athletes

All in all, this is fascinating stuff. During the same workout performed at the same level of performance, the physiological, psychological, and emotional impact of that workout is dramatically altered simply by running without or without a group. Just the presence of other human beings is capable of divorcing the relationship between internal load and external load! And since training is often performed in both group and individual settings, it’s important to understand the varied impact of these training settings. A simple change can have a major impact on what athletes experience, even if the performance is exactly the same.

For athletes who train both collectively and individually, these results may not be particularly surprising, but they are very compelling. A simple change to running with others can dramatically change the physiological and psychological impact of a given workout, even when the workout is performed at the same absolute intensity. When it comes to long-term development, both the benefit of the workout and the cost of the workout are relevant. If something as simple as training with a group can reduce the overall ‘cost’ of the workout, that can mean better progress over time. And if athletes perceive workouts to be a more positive experience, they’re likely to want to repeat those workouts. Consistency matters!

Therefore, if you have the ability to do so, plan more of your intense workouts with a training group to ensure that you can create as much external load as possible for a given internal load. In other words, take advantage of the group dynamic to perform at the same level for less physiological cost. As the quality of your workouts are directly related to the performances you achieve later on, stacking quality workouts over time is going to be easier to do if they are less stressful. Every small advantage adds up. And just as importantly, as demonstrated by the results, you’ll enjoy the experience more!

If you’re unable to train with a group for every training session, aim to perform solo during workouts where the demand is less, and the focus is purely on the internal load. Typically, these lower intensity sessions are easier to manage physiologically and psychologically. Of course, if you have access to a training group, take advantage of it!

You may be wondering if these results applicable to other sports and other modes of training? While there is no direct evidence that’s the case, there’s no reason to expect it would be any different. Group dynamics are group dynamics and training is training. There is nothing particularly special about running in this context. Regardless of your sport, I’m sure you’ve noticed or felt these effects, even if you couldn’t ‘prove’ it or quantify it. As a coach myself, I’ve certainly noticed that swimmers often struggle when they have to perform workouts by themselves. If you participate in sports other than running, it’s safe to assume these concepts will apply to you and your training.

Reference

1. Eur J Sport Sci. 2019 Sep;19(8):1045-1052. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2019.1593510. Epub 2019 Mar 28

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.