You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Training overload: quick thinking can ensure proper recovery!

How can you ensure you stay well trained and not become overtrained? SPB looks at brand new research on cognition and recovery

When pursuing improved performance through a dedicated training program, one of the biggest pitfalls that athletes make is thinking that ‘if some is good then more must be better’. However, it’s not just that this reasoning is flawed; a relentless build up of training intensity or volume without adequate rest and recuperation can result in plummeting performance thanks to phenomena known as overreaching and overtraining.

What is overtraining?

Each time you train, you break down muscle fibres and reduce your body’s stores of energy. This means that immediately after you train, your performance potential is actually lowered. The good news is that given adequate rest and enough of the right nutrients (fluid, electrolytes, carbohydrate, protein, vitamins and minerals) needed to replenish your body’s stores, you will not only recover from that training session, but your body will also undergo a process of ‘adaptation’.

Adaptation occurs as a result of a training stimulus, and is designed to help the body become stronger and withstand that stimulus better the next time next time around. There are a number of adaptive processes that occur as a result of running. These include:

· The removal of debris and various metabolites associated with exercise (eg lactate).

· Repair to muscle fibres, which sustain micro-tears, particularly during intense or unaccustomed bouts of exercise.

· An increase in the production of relevant muscle enzymes – eg, those needed for energy production in various energy pathways, or involved in muscle protein synthesis.

· Increased activity of genes involved in the synthesis of mitochondria (the cells’ energy factories).

· Replenishment of stored muscle carbohydrate (glycogen).

However, without adequate rest and nutrition, recovery and adaptation may not occur. If there’s insufficient adaptation, you’ll fail to make progress. Insufficient recovery over the longer term on the other hand is more serious because it means the body is unable even to get back to where it was physiologically before the training session. If sustained over a number of sessions, you start to go backwards! Although periods of increased training/insufficient recovery are often referred to as ‘overtraining’, the situation is more nuanced; the severity duration of any increased workload periods can lead to very different outcomes ranging from merely functional overreaching through to non-functional overreaching, and in the worst case scenario, overtraining syndrome (see box 1 below).

Box 1: Overreaching and overtraining

When we talk about recovery, adaptation and the failure to recover, we need to distinguish between short periods of overload and breakdown (which can actually result in good adaptations once sufficient rest is taken) with a more chronic failure to recover, which can lead to serious performance decrements:

Functional overreaching - when an athlete undertakes more training intensity/volume than normal but the periods of overload are short, this is known as functional overreaching. In these circumstances sports performance will temporarily decrease in response to training, but with adequate recovery, positive physiological adaptation will occur, with a commensurate improvement in performance capacity(1,2).

Non-functional overreaching - when the periods of intensive training are long, or where adequate recovery is not taken, non-functional overreaching may occur(3). In this case, the accumulation of training and non-training stresses lead to negative effects on markers of physical and mental well being, and a decrement in performance. Depending on severity, performance capacity may take several weeks or even months to return to normal.

Overtraining syndrome – is even more severe than non-functional overreaching and occurs when all the warning signs are ignored for extended periods of time. The accumulation of training and non-training related stress results in a long-term decrease in performance, very often accompanied by physiological and psychological fatigue and/or illnesses(4). This response to a prolonged training overload has a severe impact on an athlete’s health, and can require several months or even years for a full recovery. Overtraining syndrome is often characterised by increased levels of cortisol – the body’s main stress hormone(5). In addition, decreased testosterone levels (a muscle building hormone) and lowered altered immune status are also present(6). Indeed, overtraining syndrome is classified medically as a neuro-endocrine disorder, where the normal fine balance in the interaction between the autonomic nervous system and the hormonal system is disturbed, leading to a reduced ability of the body to overcome stress and heal itself(7).

Overtraining signs

All athletes will functionally overreach at points during the year; indeed, attaining a degree of functional overreaching may actually be the goal in some training scenarios (eg an intense training camp for a week). And providing this is followed by a sufficiently long period of rest during which adaptation takes place, targeted functional overreaching can be a positive strategy for making performance gains.

The problem however is that the boundary from functional to non-functional reaching is easily transgressed. And from there, the pathway to overtraining syndrome is an easy one to be lured along. That’s because overtraining is an insidious and stealthy process that can creep up on you gradually, without you realising what’s wrong until it’s become serious enough for you to require a long layoff to recover. It follows that as well as designing your training program carefully (ie no sudden and sustained increase in volume/intensity and ensuring ample rest and recuperation), some kind of monitoring or early warning system of non-functional overreaching (or worse, overtraining syndrome) is crucial for any athlete who wants to ensure that they stay on the right side of the training vs. recovery equation.

While all athletes are different, there are a number commonly observed symptoms of overtraining, many physical but some psychological/behavioural. These include(8):

Physical

• Drop in performance

• Fatigue and tiredness

• Leaden or ‘heavy’ legs even after a day or two’s rest

• Generalised aches and pains for no apparent reason

• Frequent coughs, colds or other infections

• Weight loss

• Poor appetite

• A raised resting heart rate when checked first thing in the morning

• Restless or aching legs at night

• Loss of sex drive

• Inability to relax

• Recurrent overuse injuries

Psychological/behavioural

• Difficulty sleeping/poor sleeping patterns

• Feelings of depression, irritation or anger

• Boredom or lack of motivation

• Difficulty concentrating

• Increased sensitivity to emotional stress

Of course, just one or two of these symptoms doesn’t necessarily mean you’re overtraining. But if you start to feel tired, are experiencing an unexplained drop in performance and some of the other symptoms described above, the chances are that could be on the way to developing overtraining syndrome. And given that overtraining syndrome is known to cause perturbations of multiple body systems (neurological, endocrine system, immune system) coupled with mood changes, athletes are very likely to experience a wide array of these symptoms, not just two or three(9).

Are you at risk?

What’s the best way for athletes to know if they’re on the road to overtraining syndrome? Unfortunately, there are no simple blood tests or levels of biomarkers that can measured to give a definitive or even reliable indication of when an athlete has progressed beyond functional overreaching(10). And even if these parameters can be measured, many of them require access to expensive resources or laboratory equipment that are beyond most individuals, sporting clubs and organisations(11). Moreover, decrements in performance require physical performance testing to monitor poor adaptation and/or insufficient recovery; however regular testing along these lines is often undesirable because it only serves to further overload the athlete! The psychological symptoms described above are useful indicators (in conjunction with physical symptoms) of when athletes overstep the boundary, but of course, that’s too late when prevention rather than cure is the goal.

New research on the role of cognition

Are there any alternative methods that can reliably monitor an athlete’s recovery status, and provide an indication of when an athlete might be about to cross the line from functional to non-functional overreaching? Help might be at hand thanks to a brand new study that has delved deeply into the literature to investigate evidence of a relationship between functional and non-functional overreaching and overtraining syndrome and the cognitive ability of endurance athletes(12).

Published in the journal ‘Sports Medicine Open’, a team of Aussie researchers conducted a review study to see if there is a link between the recovery/overreaching/overtraining status of an athlete and their cognitive ability. Why the interest in cognitive ability? Well, research has clearly shown that there is a powerful association between improvements exercise capacity and improvements in cognitive function(13,14). It stands to reason that if exercise capacity is diminished due to poor recovery, cognitive ability could be similarly affected too.

What they did

After combing the literature, 221 studies were initially identified as being potentially relevant, but these were whittled down to just seven studies when the inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied:

Inclusion Criteria

· Study was peer-reviewed and original research.

· Participants were from an athlete population.

· The study explored effects of overtraining on cognitive function.

Exclusion Criteria

· Research written in languages other than English.

· Studies on population groups other than athletes.

· Studies on mental health disorders.

In these final seven studies, the participants examined were all endurance trained in either triathlon, swimming, running, or cycling, with an average age of 28-36 years. As well as measuring training loads undertaken over periods of 2-9 weeks, all seven studies included different measures of cognitive function. These tests ranged from decision making tasks, to memory and learning, and simple vigilance or reaction time tests (requiring participants to react to either a visual or audio stimulus occurring at random intervals, and responding by pressing a button). In the seven studies included, three studies used the Stroop color word test (see box 2 below), four used a variation of a cognitive reaction time test, one used behavioural tasks, and one study used psychomotor speed to determine the effect training load has on cognitive processes. Table 4 provides a summary of each of the final seven included studies.

Box 2: The Stroop Color Word Test

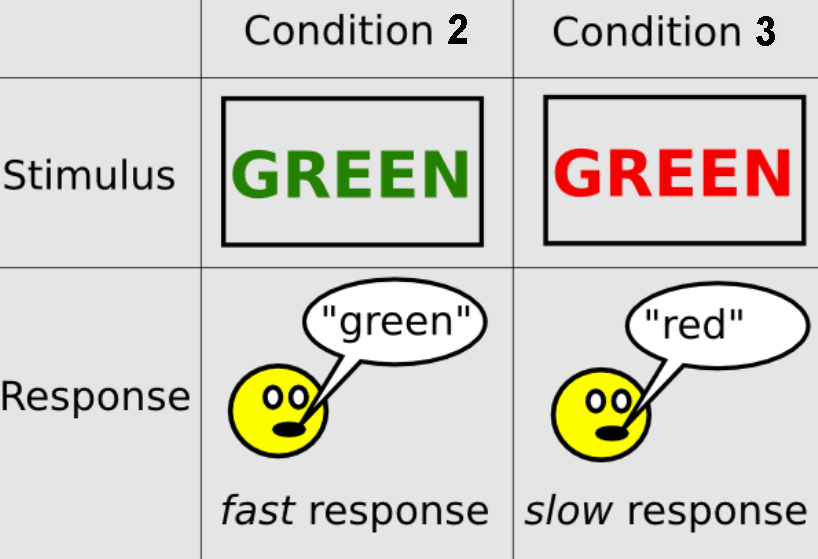

This test is used to evaluate overall executive function and measures a person’s cognitive flexibility, selective attention capacity and mental processing speed. It involves four different conditions:

• The first involves identifying colour names written in their corresponding colour (eg the word ‘red’ written in red, ‘green’ written in green etc.

• The second condition involves repeating the task but identifying the colour name written in a different colour than the word.

• The third condition involves naming the colour of a word not the word itself (eg GREEN written in red - see figure 1).

• The fourth condition is the same but includes a square appearing in 25% of trials meaning the colour of the word not the word has to be identified (ie a mix up of conditions 2 and 3).

Related Files

What they found

All of the seven studies found reaction times to be compromised (ie slower) following a period of overtraining in athletes who were likely to be crossing over from a functional to non-functional overreaching state. More generally, excessive increases in training load negatively influenced cognitive function in athletes. What was interesting was that reaction times increased in both the reaction time tests and Stroop color word tests – ie regardless of the test applied. These declines in cognitive processing were either directly related to a prescribed overload training block or athletes being in a clinically diagnosed state of overtraining.

Practical applications for athletes

The authors concluded that cognitive function was impaired in athletes who were either overreaching or in an overtrained state, and that in particular, reaction time appeared to increase with overtraining. The emphasis on reaction times is important because we know that reaction times can be up to 20% slower in overreached athletes compared to fresh athletes(15). In contrast, motor control doesn’t seem to decline when athletes are functionally overreached(16), which explains why athletes who are experiencing fatigue from training overload are able to continue training.

The fact that reduced cognition and slower reaction times (eg in the Stroop Color Test) can reliably pick up changes in the early stages of overreached (ie before athletes become non-functionally overreached or develop overtraining syndrome) is something of a breakthrough. For the first time ever, there appears to be an easy, simple and reliable way to detect ahead of time if athletes are overstepping the mark in terms of training loads.

It may also be possible to get a handle on the extent of overreaching/overtraining with these tests, because in the study above, the number of mistakes made or the error rates also increased as training overload increased. This was particularly noticeable in the studies which undertook tests at moderate to high speeds.

Using this information, we can make some practical suggestions for athletes who want to avoid the risk of becoming non-functionally overreached or worse, overtrained:

· Take a reaction time test (there are plenty online) to get a baseline when you are physically fresh (eg in the off season) and mentally relaxed (ie not stressed).

· Use a reaction time test that involves some degree of mental processing. The Stroop Colour Test is ideal in this respect).

· Record your scores when you perform these baseline tests at different speeds (overreached or overtrained athletes may perform okay at slower speeds but will struggle at higher speeds).

· After a period of heavy training or if you’ve been feeling you’re just not 100% training wise, repeat the same test and compare your scores with baseline. A drop in your score of 10% or more means you are likely overreached or worse, and need to back off workloads or cease training for a while.

· Don’t forget to monitor the other physical and mental symptoms listed above – they can also inform your decision about taking a break.

· Remember too that other lifestyle factors (eg stress, family and work demands etc) can affect your propensity to become overreached or overtrained. Factor this in when deciding if you need to back off.

· Once you’ve taken a break from your normal training for a while, you can retest to check your cognitive ability and reaction times are returning to normal before resuming training.

· Don’t ‘practice’ these tests and perform them too often; they need to be performed spontaneously to be maximally effective.

References

1. Sports Health A Multidiscip Approach. 2012;4:128–138

2. Eur J Sport Sci. 2006;6:1–14

3. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45:186–205

4. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45:186–205

5. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2021 Jul 1;16(7):965-973

6. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil. 2019 Sep 18;11:21

7. J Endocrinol Invest. 2004 Jun;27(6):603-12

8. Sports Health. 2022 Sep-Oct;14(5):665-673

9. Sports Health. 2012 Mar;4(2):128-38

10. Front Netw Physiol. 2022 Jan 18;1:794392

11. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:281–291

12. Sports Med Open. 2023 Dec; 9: 69. Published online 2023 Aug 8. doi: 10.1186/s40798-023-00614-3

13. J Sports Sci. 2012;30:421–430

14. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48:1197–1222

15. Int J Sports Med. 2007;28:595–601

16. J Appl Physiol. 2013;114:411–420

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.