You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

What form of tapering works best, and in which sports?

Athletes are gradually getting the idea that reducing their training ('tapering') prior to major competitions is a good idea, but major disagreements about exactly how to taper remain. There's considerable debate about whether one should reduce training volume (mileage or time) while preserving training intensity (speed) during a tapering period, trim intensity while maintaining volume, or simply cut back on both. There are also differences of opinion concerning how often one should train (frequency), how long the tapering period should actually last, and whether different competitive events require dissimilar tapers.

In addition to the confusion about the exact specifications of a tapering period, an additional problem is that athletes often worry that they might actually LOSE fitness during a period of reduced training. Are these athletes right'? Is there some way to construct a taper which makes 'detraining' impossible?

Fortunately, scientific research can answer many of these perplexing questions. The first good scientific study related to tapering took place in 1981, when scientists at the University of Illinois at Chicago studied 21 individuals who were training strenuously six days per week (three days of running and three days of bicycling). During their bike workouts, the subjects usually completed six five-minute intervals at close to top intensity, with only two minutes of rest between intervals. The running sessions consisted of 30-40 minutes of moderately hard running.

To see what would happen during a tapering period, one group of athletes reduced exercise frequency to just four sessions per week (two cycling efforts and two runs), while a second group cut back drastically to just two weekly workouts (one cycle and one run). The actual exercise intensity (cycling or running speed) was maintained, so frequency (the number of workouts per week) and volume (the total amount of work) were the two variables which were altered during the taper.

No fitness loss for up to 15 weeks

As the tapering periods proceeded, the Illinois scientists discovered an amazing fact: fitness was perfectly preserved in BOTH groups of tapering athletes for up to 15 WEEKS, even though frequency and total training volume were reduced by as much as 67 per cent! This startling result generated some 'Why is the emperor wearing no clothes' questions. For example, many observers began to wonder why athletes insisted on training so much, since they would be just as fit - and probably considerably less injured - with a lower amount of training. (Unfortunately, this dilemma was quickly shoved aside by the majority of athletes and coaches, who continued to cling to high-volume training. As the French like to say, it's easy to train with the nose, not the mind.) The second question was as follows: if athletes don't lose anything when training is reduced, might it not be possible to actually GAIN something during diminished-training periods, if total training were cut by just the right amount and athletes were truly allowed to rest?It's the intensity that counts

Follow-up research by the same Illinois investigative team revealed an important fact. Although carving away big chunks of frequency and volume during a tapering period usually produced no problems, reductions in intensity did lead to difficulties. In tact, almost as soon as running or cycling speed fell, fitness began to fall as well during the tapering period. It appeared that intensity was the key preserver of fitness during reduced training. This latter finding was not too surprising. After all, intensity is the best PRODUCER of fitness during regular training, too. If you want to become fitter, it's always - within reason - better to upgrade the intensity of your workouts, instead of their volume or frequency. Carrying out some intense training sessions is the optimal way both to produce and preserve fitness.Studies with swimmers

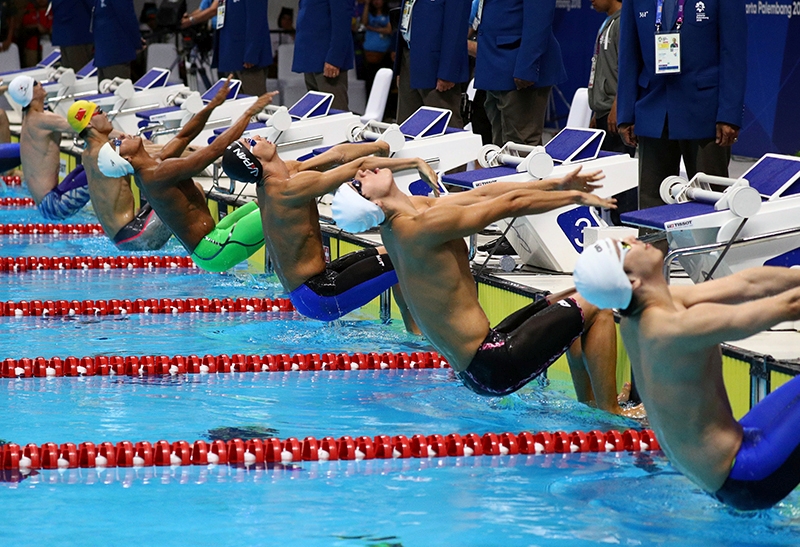

In the mid-1980's, an increased number of tapering studies began to appear in the scientific literature, most of them emanating from Dave Costill's :famous laboratory at Ball State University in the United States. In one of Costill's early pieces of research, highly competitive collegiate swimmers tapered by cutting their training volume by 68 per cent (from 10,000 to 3,200 yards per day) for 1 5 days. Over the course of this tapering period, the swimmers' muscular power soared by 25 per cent, their levels of blood lactate while swimming at rapid speeds diminished, and - best of all - their performances improved by almost 4 per cent. Indeed, Costill found that the biggest problem experienced by the swimmers was that they felt TOO good and tended to go out too fast at the beginnings of their races.Costill's work was 'fine tuned' a few years later in an investigation at Northern Colorado University. There, swimmers again cut their training to about one-third of its normal level, but this time the athletes were monitored over a four-week period. The Northern Colorado scientists found that blood lactate levels during exercise (an indicator of fatigue) tended to drop for the first two and a half weeks of tapering, but rose thereafter. Likewise, performances improved over roughly the first two and a half weeks but declined during the last week and a half of the experimental period. The Northern Colorado study suggested that it might be wise to extend a tapering period to about two and a half weeks - but not longer - in order to 'milk' out all possible benefits. Longer tapering periods didn't seem to work.

Is a one-third training cut enough?

Since athletes in the University of Illinois study had trimmed training volume to one-third of its normal level for 15 weeks without any repercussions, and since both the Northern Colorado and Ball State swimmers had also cut training to 33 per cent of normal and had experienced big physiological and competitive gains, a tapering concensus emerged. Knowledgeable coaches and athletes began to think that training volume should be cut to about one-third of its usual level during an optimal taper. A runner who normally covered 40 miles per week could cut back to 15 weekly miles during a tapering period, for example. However, several questions still hadn't been answered. No one knew much about intensity, for example. Since intensity was the key preserver of fitness during a tapering period, should average workout intensity actually increase during a taper, or should it simply be kept the same, or should it be slightly reduced in order to maximize rest? And what about frequency? Would it be wise to take complete days off from training during a tapering period, or was it best to train lightly every day?The skeptical athletes

In addition to the confusion about frequency and intensity, another problem was that athletes simply didn't believe the scientists' contention that training volume should be cut by two-thirds during a taper. Athletes addicted to the 'work-work-work' method of training and the 'more is better' philosophy had a very difficult time accepting the idea that less training could make them stronger or faster. Also, many athletes were quite obsessive about their body weights and believed that a trimming-down of training volume would automatically lead to increases in corpulence. Among the athletic community, therefore, tapering periods continued to be kept as abbreviated as possible. Unfortunately, news that world-best Kenyan runners were only tapering for a few days before major competitions also fueled the belief that the tapering information emerging from scientific laboratories was 'ivory-tower' stuff which had little relevance to real athletes trying to win important competitions.In fact, the athletes' stubborn beliefs flew in the face of a training principle which exercise physiologists had known about for a long time. This principle can be stated as follows: with a few exceptions, the physiological benefits of a workout usually don't show up until at least 10-14 days have passed after the workout, a time period during which the body is adjusting and (hopefully) rebuilding after strenuous exercise. A logical question to ask the athletes, then, would have been, 'Why are you working so hard during the final two weeks before your big competition, when the benefits won't show up until after the event is over?' No one posed this query, though, since most coaches and 'experts' believed in abridged tapering, too.

And now-the 90 per cent cut!

Meanwhile, tapering research continued, and a real tapering breakthrough occurred in 1990, when Duncan MacDougall and his colleagues at Mc Master University in Ontario, Canada, pulled out all the stops and asked a group of runners to trim their training by almost 90 per cent during their tapering period! Another group followed the usual strategy of cutting back by two-thirds, and yet a third group did absolutely no running at all during the tapering period, which was one week in duration for all three groups.An unusual feature of the 90-per-cent-cutback group's training during the tapering period was that almost all of the mileage consisted of fast 500-metre intervals at about one-mile race pace. In fact, the athletes ran five 500-metre intervals on the first day of the taper, four 500-metre intervals on the second day, three 50()-metre intervals on day three, etc., and rested completely on day six. On the seventh day, they participated in performance tests. MacDougall had set up the taper in this manner, with an almost total emphasis on fast intervals, because he was aware that intensity was the most potent way to preserve - or build - fitness during a tapering period.

Amazingly enough, endurance (measured as the length of time the runners could run at a quality pace) skyrocketed by 22 per cent in the 90-per-cent-cutback group after the tapering period but increased by only 6 per cent in the regular-taper group (the group which had performed only easy running at one-third of their normal volume). The do-nothing taper produced...well...nothing in the way of performance enhancement.

Why did the strange, 9()-per-cent-cutback taper work so well? First, these speedy taperers stockpiled more glycogen in their leg muscles, suggesting that perhaps the traditional, previously accepted, two-thirds diminishment of training volume in fact wasn't enough of a curtailment to allow muscles to completely restore their energy levels.

In addition, levels of key energy-producing enzymes advanced to a magnificent extent in the strange-taper group, indicating that almost-complete rest (with training comprising only 10 per cent of normal volume) was needed to give muscles a real chance to synthesise mega-quantities of important ergogenic chemicals.

Finally, the strange-taper runners had much higher blood volumes, compared to runners using the more conventional tapering strategy. High blood volume is extremely beneficial, because it permits more red fluid to gush toward the leg muscles during strenuous exercise, bringing along bumper crops of oxygen and fuel. It seemed that this flood of blood was induced by the fast intervals included in the strange taper, because one of the key acute effects of an intense (but not a moderate or easy) workout is an expansion of blood volume.

To summarize, the Canadian study showed that if you cut back on your training by 90 per cent and let fairly intense work make up most of the remaining training which you do carry out, you may be astoundingly better after just one week. This finding was subsequently verified by researchers at other laboratories.

An additional bonus for athletes using this 90-per- cent plan is that 'strange' tapering training, consisting of intervals conducted at close to race pace, prepares them for the exact neuromuscular requirements needed on race day. In other words, they'll need to run or cycle or swim at a specific goal pace on the day of their important competition, and 'strange' tapering allows them to practise this tempo repeatedly during their tapering periods. As a result, their nervous and muscular systems learn to handle this pace in an energy-efficient and relaxed manner, and mental confidence also soars. A 'strange-tapered' athlete will often think, 'I can deal with this pace; it's one that I've practised often.' On race day, the athlete will settle into the pace almost without thinking. Exercise economy will improve, the feeling of mental effort associated with the pace will decline, and there will be little chance of going too fast or too slow during early moments of the competition.

Testing it in an actual race

The Canadian study was reinforced by research completed at East Carolina University in the United States in 1993. There, eight experienced runners (six males and two females) who had been running about 43 miles per week cut their training to just 6.5 miles of interval training and about seven miles of warm- up and cool-down jogging for a one-week period. The interval work consisted almost exclusively of 400-metre intervals conducted at current 5-K race pace and represented just 15 per cent of usual weekly mileage. As in the Canadian study, the intervals were arranged in a 'descending-escalator' fashion: there were eight intervals on the first day of the taper, five on the second day, four on the third day, etc. Recovery between intervals consisted of walking or resting, and a new interval was started when heart rate dropped to 100-11O beats-per-minute.Although the East Carolina protocol was similar to the Canadian work, there was one key difference: the East Carolina scientists actually tested their athletes in a 5-K race. The results were spectacular. All eight athletes improved their personal-best 5-K performances, and the average improvement was a not-too-paltry 29 seconds, or over nine seconds per mile. As predicted by the arguments presented above, running economy also improved (by 6 per cent). Meanwhile, runners who had not followed the 'down- escalator' tapering scheme failed to enhance their performances at all.

The conclusion to draw from the East Carolina work is that the best tapering plan for a 5-K race is to simply complete about 10-15 per cent of one's usual volume by carrying out relatively short, race- pace intervals, with a small amount of additional warm-up and cool-down exercise, over a one-week period. Could the same taper work for longer races? Although the East Carolina research looked only at 5- K performances, it is likely that the same taper would work equally well for the 10-K, and by extension (for cyclists and swimmers) in events lasting about one hour or less.

One problem with the Carolina work, however, was that many runners experienced muscle soreness as the week went along. They simply weren't used to doing so much interval work! It's remarkable that they did so well despite being sore, and it's possible that they could have done even better without the muscle distress. Therefore, it' s reasonable to suggest - if an athlete is vulnerable to muscle soreness - that these same intervals be conducted about once a week during the weeks leading up to competition, so that the muscles have time to adapt to the interval training. If that' s not possible, the intervals could be completed every other day, rather than every day, during a tapering week, with a very short bout of light exercise replacing the missing interval days. With the soreness eliminated, this plan might produce even greater gains in performance.

Endurance events

What about longer competitive events like the marathon for runners or multi-hour races for cyclists? Should they also be preceded by a low-volume, high- intensity, one-week taper? For the marathon, the answer in most cases is no. Scientific studies now confirm that most marathon trainees actually damage their leg muscles during their race preparations, more so than on race day, by doing too much mileage and not giving their leg muscles adequate time to recover from the micro-trauma that is an inevitable consequence of high-volume training.Since muscle trauma associated with high-mileage running takes about a month to repair, it's only logical that the tapering period for a marathon should last at least a month. After all, who wants to run a challenging race like the marathon with damaged sinews? Of course, most marathoners either howl with derision or throw their hands up in despair when they hear about one-month tapers, fearing a loss of fitness or a departure from conventionality, but neither is a big concern. Regarding the potential loss of fitness, remember that the University of Illinois-Chicago work showed that fitness could be perfectly maintained for up to 15 weeks as long as high-quality workouts were included in the abbreviated programme. As for the loss of conventionality, just do it!

The exact formula for a pre-marathon taper hasn't been investigated scientifically, but it's likely that about a '75-50-30-15' plan (75 per cent of usual miles in the first week, 50 per cent in the second week, etc.) would work well. During the final week, the idea would be to focus on interval training equally divided between 5-K-paced and marathon-tempo intervals, with a gradual reduction in the number of intervals conducted per day. During the initial three weeks, it would be important to sustain the normal frequency of high-quality training (intervals, reps, tempo runs, etc.), while cutting away the long miles at slow velocities. Again, any fears about detraining can be dispelled by the Illinois research, which observed no losses in fitness over 15 weeks of reduced training.

Long-distance cyclists and swimmers have less muscle damage, so they may not need such an extended taper; perhaps two to two and a half weeks will be all that is necessary to restore muscle glycogen and synthesise abundant quantities of muscle enzymes. Likewise, participants in 'skill' sports such as tennis and squash can probably get by with just a seven- to 10-day taper before a major competition.

The amazing benefits of tapering

To conclude, tapering works by producing an incredible array of positive changes for athletes, including augmented glycogen stores, increased aerobic enzymes, expanded blood plasma, upgraded economy, better repair of muscle and connective-tissue trauma, improved neuromuscular coordination, and heightened mental confidence. One reason that optimal tapering works so exceedingly well - in the athletes who really carry it out - is that most athletes probably compete while they're still tired from their previous training. These athletes haven't given themselves an adequate chance to recover from their strenuous training, and therefore their muscles can't function at the highest-possible level on race day. When these athletes try a real taper, many of them reach their true potential for the first time in their livesShould you taper as part of your regular training?

Non-tapered athletes are the victims of an all-too- popular belief in sports, which is that good training consists of little more than very, very hard work. This approach fails to take into account the reality that great training is always a combination of work AND rest. Without appropriate rest, the human body simply can not fully adapt to training. While putting together an optimal training schedule, an athlete must consider the rest days and periods just as carefully as the hard- training times. Otherwise, he/she will always compete in a sub-optimal state.That consideration brings up an important follow- up point. Since appropriately constructed tapering can produce such incredibly positive results, and since many athletes train far too much, with too little recovery, why not include tapering periods not just before races but as a regular part of the overall training programme? This would lead to big upswings in fitness, not just before competitions, but at regular intervals during training. The timing of such tapering would depend on the intensity and volume of an athlete's schedule, but - at the very least - the final five to seven days of each month should be made light enough to 'consolidate' all the potential gains which can accrue from the first 21-25 days of regular training.

After reading about all the good tapering research, are you still a tapering sceptic? Are you the kind of person who says, 'The Kenyans don't taper, so why should I?' If so, please bear in mind several things. First, the Kenyans, having trained from the age of six onwards, are probably more adapted to training than most other runners and can probably get by with less tapering. Second, most of the Kenyans DO drastically cut back on their training when they are feeling tired, and most also take a full month off from training every year. Finally, the Kenyans might actually be even better if they tapered a bit more before their competitions!

The bottom line is that tapering is very, very good for you. If you're aggressive with your tapering - carving away big chunks of your usual training volume while maintaining reasonable amounts of high-intensity exercise - you will usually be able to carve away large chunks from your race times as well.

Owen Anderson

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.