You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Covid-19 and the athlete: mental resilience matters

What have been the most effective psychological coping strategies for elite athletes during the covid-19 pandemic and what can we learn from their experiences? SPB looks at new research

At the start of the covid-19 pandemic, the popular mantra was ‘three weeks to flatten the curve’. Now over a year later, many populations across the globe are still living under varying degrees of government-imposed restrictions, ranging from relatively ‘light-touch’ measures such as cancellation of large events and social distancing to full-on ‘stay-at-home’ lockdown mandates. Many of these measures have been especially impactful on competitive sport, with many events cancelled completely in the 2020 season, and considerable uncertainty remaining about the full resumption of sport in the 2021 season.The pandemic and athletes

In the context of the suffering caused by the virus itself and the economic fallout caused as a result of the restrictions put in place, the impact of the pandemic on (mainly healthy) athletes may seem inconsequential. However, the emotional, psychological and health impacts of the restrictions over the past year have been very real for many athletes. After all, in most respects, athletes are no different to any other citizens, and over the past year, the pandemic and measures that followed have caused industry closures, changed daily life patterns, financial losses and unemployment, and disrupted social and community support - all of which have a clear psychological impact(1).Preliminary findings from studies on this topic indicate that social isolation caused by lockdowns typically resulted in around 20 hours per day spent at home, chronic exposure to stress, loss of daily routine, self-protective behaviors, elevated anxiety levels, and depressive symptoms, including anger, helplessness, guilt and shame(2-5). For athletes where sport participation is a key pillar of day-to-day life, these kinds of psychological reactions have been compounded by the cancellation or modification of sporting events, the disruption to normal training routines – for example not being able to train with others (or even outdoors in some countries) – travel restrictions and reduced/zero access to coaching. Even many of the largest sporting events such as the Olympic Games (which for many athletes are highly motivational) have been cancelled or postponed indefinitely, underlining how normal life as athletes knew it has radically changed.

Impact on athletes

Given the above, researchers have called for a thorough investigation into the influence of COVID-19-related changes in elite sport(6). Some preliminary data has looked into athletes preparing for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, and the fallout following postponement(7,8). It found that even before formal postponement, many athletes felt as though the uncertainty (will they/won’t they go ahead?) meant that their life plans were in flux, causing stress responses. After postponement, these athletes experienced a range of responses from constructive (a sense of increased resilience brought about by adequate coping mechanisms) to debilitating (burnout syndrome, feelings of alienation, and poor coping compounded by social isolation). The issue of social isolation may be especially problematic as an abrupt diversion in an athlete’s career, could also trigger dissociations from an athlete’s ‘identity’ and negatively impact their mental health(9).Resilient athletes

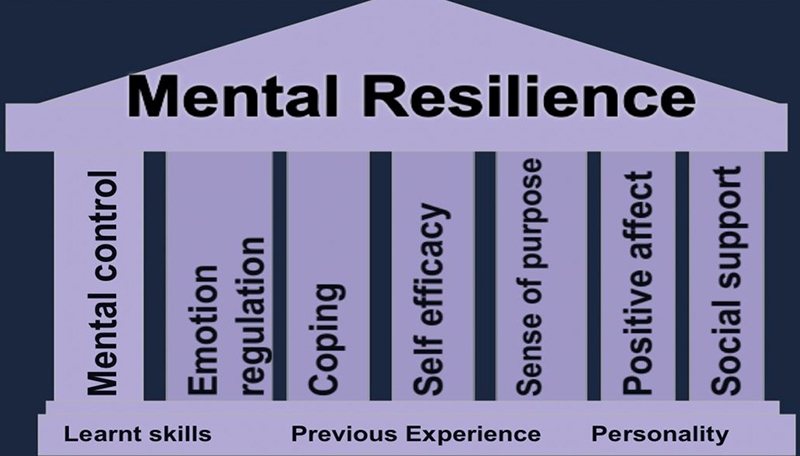

Clearly, athletes with greater psychological resilience have been and will continue to be better equipped to deal with the covid-19 related changes to sport we are currently witnessing. But what exactly does ‘psychological resilience’ mean in the context of sport? In general terms, psychological resilience has been defined as ‘the role of mental processes and behavior in promoting personal assets and protecting an individual from the potential negative effect of stressors’(10). Contextualized to the sporting context, sporting resilience can be further defined as ‘the environmentally adaptable, cognitive, emotional and behavioral capacities of an athlete to maintain a positive equilibrium and successfully adapt to a diverse range of sport-related adversities’(11). These capacities arise from a combination of learnt skills, previous experiences and personality characteristics (see figure 1)(12).Figure 1: Elements of mental resilience*

Research suggests that key elements of resilience arise from a combination of learnt skills, experience and personality traits. * adapted from Precious and Lindsay “Mental Resilience Training”(12)

Since most athletes are still engaged in drawing upon their ability to become and remain resilient (since the threat of the covid-19 adversity to physical and mental health remains), an obvious question to ask is how can athletes build and develop resilience to deal with these changes going forward? Unfortunately, although the scientific literature provides many commentaries, theoretical frames, and perspectives about what could be involved, there is little empirical evidence (ie hardcore data) to draw upon in order to understand covid-19 related resilience. However, newly published research into this topic by British scientists has explored the nature of adversities faced by actual competitive elite athletes during the global covid-19 lockdowns in order to understand the complexity of the process of resilient adaptation(13).

Published in the journal ‘Frontiers in Psychology’, researchers from the University of Glasgow set out to define the exact nature of the adversities faced by athletes and factors behind the process of resilient adaptation. The study employed an across-cases qualitative design comparing the real-time lived experiences of athletes during COVID-19 using narrative analysis. Data were collected from competitive elite athletes from various countries across the globe during the lockdown period, using in-depth experiential interviews. Competitive elite athletes were approached since they were likely to have resilient characteristics that enabled them to withstand stressors for achieving success in their sport(14). Both team and individual athletes were included to provide a holistic idea about the nature of the adversity and the process of resilience in times of isolation.

Data was collected using a semi-structured interviews lasting around an hour for each athlete. The questions offered athletes the space to discuss their experience of covid-19-related adversity and how they engaged their resilience. The interview questions were open ended, and the participants were told to be conversational. At the time of the interview, all participants were residing in countries with complete national lockdowns. To ensure methodological rigor, authentication strategies such as peer debriefing during the research process to ensure credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability were used. Coding was done initially by the first author and independently checked by the second author. Credibility was also ensured through a process of ‘triangulation’, where interview transcripts and interpretations were checked with the participants where possible, which ensured that the rigor and data analysis were not biased.

The key findings

The full text paper provides a number of in-depth responses from individual athletes, but for the sake of brevity, we will summarize here.A – The adversities experienced

- Loss of sport, support, and identity - Loss was a recurring part of the adversities faced by the athletes during COVID-19 lockdown. One athlete named Jack summarized this succinctly when he exasperatedly stated, “I have never had 8 weeks where I have not stepped on a badminton court; so, it’s weird.” This feeling of losing a sense of normality is associated with the loss of their sport (ie ability to engage in sport, train, and compete was echoed by all participants). The narrative also encompassed adverse emotional reactions to this loss.

- Loss of positivity - Loss of sport and training also had a tangible effect on the mental health and psychological side of sport, which was also lost. Athlete Alex noted how the “psychological environment is important “If you’re around people who are negative then it’s a factor, and now there are a lot of people who are understandably negative.”

- Loss of support - Another major loss experienced by athletes has been the loss of support and having good sport support systems. As Jack noted: “For us, we have got the coaches, the physios, the psychologists, and the sport performance lifestyle people. Having these people around, people you can chat to, and have, like, honest conversations with - I think the sport staff and having a good environment rubs off on you and the players that you are training with, and this COVID-19 thing has prevented that.”

- Identity loss - Although not explicitly stated, the athletes indicated a loss of identity caused by the prevailing conditions. This was seen in the descriptions of the way the participants struggle to describe themselves away from the dominant sport-culture performance narrative, despite having no actual sport participation and competition. Interestingly, all participants followed this pattern identification of athlete role and hinted at a sense of reduced accomplishment due to the covid-19 pandemic, along with a corresponding loss of cognitive and social utilizations of their athletic identity.

- Incongruence – All the athletes experienced a sense of incongruence. This incongruence represented a form of dissonance between the usual structured, goal-directed environment they were acclimatized to and the relatively aimless isolation situation brought about by the pandemic. This incongruence manifested in feelings of impotence, and morphed into psychological distress, ruminations, negative emotions, and loss of motivation, constituting a major adversity. Athlete Tessa recounted the effects of her incongruence and the unstable COVID-19 situation: “So I really struggled with aiming toward something…. And I got a bit out of the habit of doing or giving my full effort to some of my workouts because I really was struggling my motivation, because I kind of felt what’s the point?”

- Loss of perfection - All the participants discussed feeling the need to live up to ideal perception of what an elite should be and their struggles with it. “Perfect” and “should” came up multiple times in every participant’s narrative. Athlete Maria” noted that, at times, she has tried to maintain a routine and ‘control the controllable’: “So I trying to control the things that are in my control and all the little things that I do. I can’t say I am a perfect example because I have definitely struggled as well ‘cause it has not been easy not having those distractions in your life, like, playing, that is my passion.”

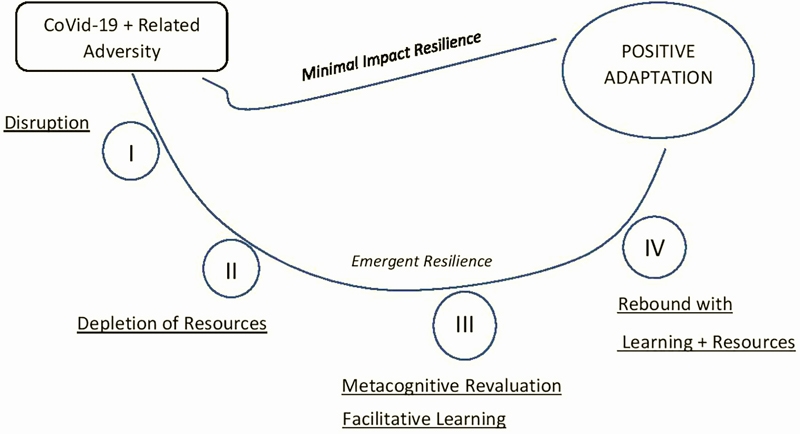

- All the participants engaged in a ‘positive reframing and challenge’ appraisal in order to develop resilience. However, because of the acute, unprecedented nature of the pandemic, no participant reported progression of resilience response along the ‘minimal impact’ resilience pathway (see figure 2). This was to be expected; the nature of the pandemic and the global lockdown were not previously experienced or even heard of by the participants, which meant that they didn’t have existing resources to engage in a resilience response and maintain well-being. Instead, their responses had to be developed ‘on the fly’ by using an ‘emergent resilience’ pathway.

- Stage 1 of the athletes’ responses was a sense of disruption while in stage 2, athletes recounted an acceptance of the reality and a corresponding emerging resilience response, even though this was typically accompanied by a depletion of resources. Athlete Natasha explained: “It’s been such a fast-evolving thing and everything is changing. You have just got to go with it since you can’t not go with it. We are all learning and we are all on the same page - it’s a bit of a rubbish situation, just let’s get on with it.”

- This acceptance of the unusual and the various adversities resulting allowed the athletes to engage in a ‘challenge appraisal and learning’. This appraisal included looking beyond the athlete’s individual adversity and looking at the larger world - since the pandemic is a planetary phenomenon. As athlete Rohan noted: “We are all going through a bad time, and my resilience has allowed me to have that positive perspective to think that it’s not just me, it’s the whole world who is facing this. And I know that, over the next few months, we will recover from this.” This acceptance actually indicates a resilient response since adversity anxiety usually prompts self-rumination and tunnel vision thinking.

- Following this acceptance, the athletes developed techniques and strategies to cope and increase their resilience. These included the increased use of social support in an innovative manner, learning and mastering positive imagery and relaxation techniques, re-evaluation of the athlete’s relationship with sport and taking time to analyse and learn about their core values and motivations for engaging with sport.

Figure 2: Model of resilience trajectories adapted to covid-19*

When previous experience or learnt skills already exist, positive adaptation can occur via the direct minimal impact pathway. However, in this completely unprecedented situation, athletes had to follow the emergent pathway (*adapted from Bonanno and Diminich, 2013)

Implications for athletes

This is the first study investigating actual athlete responses to the huge changes brought about by the pandemic. The data shows that the adversity experienced and the consequent resilient response by competitive elite athletes is different to the usual and expected responses. It is different for several reasons:- There is no prior experience to draw on, which is a core component of generating a sense of mastery key to resilience.

- Many usual resources accessed to enable a resilient response such as perceived/tangible social support, motivational climate and identity are not available.

- Loss of training and sport also constitutes a loss of an adaptive coping mechanism, which is often used by athletes(15).

- Resilient athletes however diverged from the general adaptive tendency (which involves avoidance of situations involving threat uncertainty and feared potential averse emotional impact) by engaging with the adversity and disruption and undergoing a re-evaluation and learning process – ie adopting the emergent resilience process trajectory.

What are the implications of these findings for athletes, their coaches and their support teams? Here are some useful pointers:

- Context – Setting a mental framework or context for the athlete can help produce a resilient mindset. A helpful analogy for the covid-19 pandemic is to liken it to other similar acute, long-term, restrictive adversities and uncertain, non-controlled change events. A textbook example is a sudden long-term injury or other complex experiences. Both in covid-19 and long-term injury, the endpoint to return to ‘normal’ sport is unknown, but athletes still have to process and continue with their career preparation.

- Psychological support - Support should be focused on the maintenance of mental health and the development of psychological coping skills for self-care rather than performance indices. For work with adolescent and early collegiate athletes, introducing psycho-educational life skill training in addition to therapeutic support will form a more holistic approach for intervention. As part of this process, athletes should be encouraged to move away from a ‘fixed’ mindset to a ‘growth’ mindset, which improves resilience. Athletes should also be reassured that they are not alone in their struggles and that other athletes across the globe are all facing similar challenges.

- Self-regulation - Another recommended intervention strategy is to facilitate the development of improved self-regulation behaviors in athletes, which is an important protective factor of resilience among youth at risk of social exclusion and in sport(16). This can help promote a sense of control and environmental mastery, which in turn promotes resilience(17). (see this article for more on self-regulation)

- Communication skills – athletes and their coaches should upskill themselves as much as possible to enable the best digital communication possible when meeting in person is not possible. Although not a substitute for the face-to-face communication, it can nevertheless perform a useful support tool for athletes seeking to find a pathway through.

- Perspective – Coaches, sport psychologists and athlete carers should endeavour to understand the situation from the athlete’s perspective and engage their feelings, in order to better provide support. As part of this, athletes should be seen as individual people, each on their own trajectory and facing unique challenges, rather than merely units of performance.

- Ann. Acad.Med. Singapore 2020; 49, 1–3

- J. Sleep Res. 2020:e13052. doi: 10.1111/jsr.13

- Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020 17:2032

- Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:1729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729

- Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2020 14:119

- Manag. Sport Leis. 2020 doi: 10.1080/23750472.2020.1750100. [Epub ahead of print].arnell et al.

- Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2020 18, 269–272

- Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2020 18, 409–413

- Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2010 11, 1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2009.09.005

- Sport Psychol. Action 2016 7, 135–157

- Gupta, S., andMcCarthy, P. J. (in press). A systematic review of sporting resilience: definitional advancement and evidence-based meta-model. Int. J. Sport Exerc.Psychol

- BMJ Military Health 2018 vol165 issue 2

- Front Psychol. 2021 Mar 3;12:611261. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.611261. eCollection 2021

- Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2012 13, 669–678

- Sport Psychol. 2000 14, 63–80

- Int. J. Physiol. Nutr. Phys. Educ. 2019 4, 843–848

- J. Sports Sci 2014 32, 1419–1434

Related Files

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.