You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Intense training – can you have too much of a good thing?

Given the universal endorsement of moderate activity, and the much publicised deaths of Jim Fixx, Marc-Vivien Foe, Reggie Lewis and other famous athletes, the serious athlete could be forgiven for thinking he or she is training too hard, . However, back in 2006, Dr Gary O'Donovan reviewed the scientific evidence about whether, in the interests of health, the serious athlete should give-up high-intensity exercise in favour of brisk walking. It turns out that strenuous exercise is even better for your health than you might imagine...

Diseases of inactivity are the leading cause of death in the UK.1 In England and Wales, rising levels of obesity and type-2 diabetes are thought to have caused around 5,000 additional deaths between 1981 and 2000.2 More alarmingly, coronary heart disease (CHD) is thought to have caused over 40,000 premature deaths in the UK in 2002.3 There is no genetic explanation for the increased prevalence of these diseases, as the genetic makeup of man has changed little during the past 10,000 years.4 Rather, obesity, type-2 diabetes and CHD are ‘lifestyle diseases’ that can be prevented.Why is moderate activity recommended for health?

Traditionally, it was recommended that 20 to 60 minutes of aerobic exercise be performed three or more times per week at 60 to 90% of maximum capacity.5,6 Although these recommendations were designed to improve aerobic fitness, it is likely that most individuals did not distinguish between the health benefits of physical activity and physical fitness.7 More recently, the American College of Sports Medicine has published separate guidelines on physical activity8 and physical fitness.9 ‘Exercise for fitness’ and ‘physical activity for health’ concepts were distinguished in the belief that ‘the amount of activity is more important than the specific manner in which the activity is performed.’8After this schism, individuals were encouraged to pursue ‘active lifestyles’ rather than aerobic fitness.10 To become more healthy, British and American adults were advised to accumulate at least 30 minutes of moderate activity on five or more days of the week.8,11 Physical fitness guidelines continued to endorse aerobic exercise, but greater emphasis was placed on moderate-intensity training in the belief that high-intensity exercise was accompanied by greater risk of cardiovascular and orthopaedic injury.9

It was also thought that low- to moderate-intensity activities were more likely to be continued than high-intensity activities.8 Although moderate interventions are often more successful,12 several studies have found no difference in injury or dropout rates between moderate- and high-intensity groups.13-16 The best available evidence also suggests that physical activity levels have continued to fall since moderate guidelines were introduced.2,17

Is vigorous exercise better for health?

Several large studies have found that cardiovascular and all-cause mortality are lower among vigorously active individuals than among moderately active individuals. In a nine-year study of 18,000 British civil servants, the CHD rate among office workers who took part in swimming, running and other vigorous activities was less than half the CHD rate of office workers who reported no vigorous exercise.18,19 This pattern was observed in smokers, those with high blood pressure and those with a family history of CHD, suggesting that vigorous exercise exerts protection independent of other risk factors.In the Harvard Alumni Health Study, the relationship between physical activity and CHD has been assessed at different time points in men who enrolled at Harvard University between 1916 and 1950. Baseline and follow-up questionnaires sought information about walking, stair climbing and participation in sport and exercise. In an early report, an inverse relationship between physical activity and all-cause mortality was observed in 17,000 men followed for 22 to 26 years.20 However, participation in non-vigorous activities was not associated with longevity. A similar pattern was observed in a more recent study of 13,500 alumni.21 It is not surprising, therefore, that the authors of the Harvard Alumni Health Study have concluded that ‘a half hour of vigorous activity expends as much energy as moderate activity carried out for twice or three times as long – and it can provide greater CHD benefits.’22

The recent Health Professionals’ Follow-up Study is noteworthy because of its large sample size and its rigorous methodology.23 The cohort consisted of 44,500 health professionals, from dentists to veterinarians, aged 40–75 years, followed from 1986 to 1998. Physical activity was assessed at baseline and at two-year intervals using a questionnaire. CHD risk was reduced by 18% in those who walked 30 minutes per day. More encouragingly, CHD risk was reduced by 42% in men who ran for one hour per week. Men who consistently engaged in any form of vigorous exercise enjoyed a 30% reduction in CHD risk compared to men who maintained a low level of exercise. Interestingly, men who increased exercise intensity from low to vigorous enjoyed a 12% reduction in CHD risk. This temporal sequence supports a causal relationship because the exposure (exercise) preceded the outcome (risk reduction). This study of health professionals reached a similar conclusion to that of Harvard alumni: brisk walking may reduce CHD risk but greater protection can be gained by engaging in more intense exercise.23

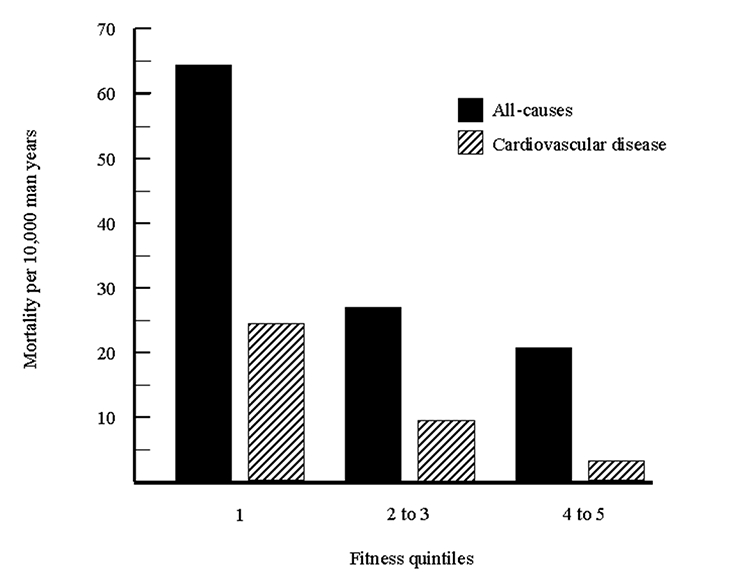

Since 1970, more than 25,000 individuals have attended a preventative medical examination at the Cooper Institute for Aerobics Research in Dallas, making the Aerobics Centre Longitudinal Study the largest investigation of the health benefits of physical fitness. In an early report, physical fitness was measured in 10,224 men and 3,120 women before 8 years of follow-up.24 Fitness categories were determined using age and gender-specific treadmill times derived from a maximal test protocol.25 As shown in Figure 1, there was a strong inverse relationship between physical fitness and cardiovascular mortality and between physical fitness and all-cause mortality. A similar relationship was observed in a later study of 25,341 men and 7,080 women.26

Figure 1. Age-adjusted all-cause and cardiovascular death rates in 10,224 men by physical fitness groups (least fit in quintile one). Data from Blair and colleagues.24

The relationship between change in fitness and cardiovascular mortality was also investigated in the Aerobics Centre Longitudinal Study.27 In 10,000 men given two preventative examinations separated by 5 years, cardiovascular death rates were highest in men who were unfit at both examinations (65.0 per 10,000 man-years). The lowest death rate was observed in men who were fit at both examinations (14.2 per 10,000 man-years). Unfit men who became fit between the first and second examination had an age-adjusted cardiovascular death rate of 31.4 per 10,000 man-years, corresponding to a reduction in risk of 52%. Sub-group analysis of 1,500 men showed that change in fitness was associated with change in activity, suggesting that the observed improvements in fitness and CHD rate (i.e., the outcomes) were the result of a more physically active lifestyle (i.e., the exposure). In agreement with a study of 6,000 men28 and a study of 87,000 women,29 the Aerobics Centre Longitudinal Study has also found that the risk of type-2 diabetes is lower among vigorously active and highly fit individuals.30

The Aerobics Centre Longitudinal Study has consistently shown that the greatest improvements in health occur between fitness quintiles 1 and 2; that is, between so-called low-fit and so-called moderate-fit individuals. These findings have influenced current activity guidelines that emphasise moderate activities such as brisk walking.8 Current guidelines are a misinterpretation of the Aerobics Centre Longitudinal Study, however, and adherence to them is unlikely to provide a training stimulus sufficient to improve fitness to a level associated with protection from CHD. To enter fitness quintile 2 and enjoy any protection from disease, an aerobic capacity of 11 METs is required at age 40–49 years (one MET is equivalent to the energy expended at rest).31 Brisk walking requires only 4 METs.32

Meta-analysis is a statistical technique that allows the results of several studies to be combined to reach a more powerful ‘consensus.’ A meta-analysis of 23 studies is shown in Figure 2.33 Notice that the dose-response curve between physical fitness and cardiovascular disease risk is curvilinear: there is a dramatic fall and subsequent taper. The dose-response curve for physical activity and cardiovascular disease risk is not curvilinear. Rather, a gradual reduction in cardiovascular disease risk occurs with increasing levels of physical activity. For this reason, it was concluded that current physical activity guidelines exaggerate the health benefits of moderate amounts of physical activity.33

Figure 2: Relative risk for cardiovascular disease derived from a review of 23 large studies cited in the U.S. Surgeon General’s report on physical activity and health.56

Can we have quantity and quality of life?

The work of James Fries and colleagues at Stanford University provides perhaps the most compelling endorsement of a lifetime of vigorous exercise. In agreement with the Harvard Alumni Health Study,21 Fries and colleagues have found that habitual exercisers live longer.34 More unusually, Fries and colleagues have shown that habitual exercisers enjoy a longer period of disability-free life.34,35From 1984 to 1997, Fries and colleagues assessed the quality of life of 370 members of a runners’ club and 249 non-runners initially aged 50–72 years.35 A ‘disability score’ was derived from a questionnaire about functional ability in 8 areas: rising, dressing and grooming, hygiene, eating, walking, reach, grip and activities such as running errands. The disability score was lower in runners at every age and the development of disability associated with some difficulty in performing everyday activities was delayed by 9 years in runners compared to non-runners.

In a study of 1,741 middle-aged men and women, Fries and colleagues34 also found that the development of disability was higher among smokers, non-exercisers and the overweight. They concluded that, ‘Not only do persons with better health habits survive longer, but in such persons, disability is postponed and compressed into fewer years at the end of life.’34

Nature or nurture?

Low aerobic fitness is a powerful predictor of CHD mortality, even among healthy middle-aged men.36,37 Nonetheless, it has been suggested that the relationship between physical fitness and CHD is explained by self-selection, rather than a protective effect of exercise. This would be the case if individuals who chose to exercise were inherently healthier and at lower risk of CHD than those who chose not to exercise.38 The Copenhagen Male Study was designed to test the notion that ‘naturally fit’ men enjoy protection from heart disease in the absence of prior exercise training.39 Physical activity and physical fitness were measured in 5,000 middle-aged men before 17 years of follow-up. Among inactive men, CHD rates were comparable in the unfit and the highly fit (10.1% and 14.1%, respectively). In active men, conversely, CHD rates fell as fitness increased. These data suggest that the protective effects of physical fitness are mediated through physical activity and that ‘naturally fit’ individuals do not enjoy a selective advantage that confers both the capability for high levels of physical activity and protection from CHD.In Finland, 16,000 twins were studied over 17 years in an effort to dismiss any suggestion of a genetic predisposition that confers both the capacity for vigorous exercise and longevity.40 In same-sex twin pairs, the risk of death was 44% lower in those who undertook vigorous exercise on a regular basis. Thus, it was concluded that physical activity reduces all-cause mortality even after familial and genetic factors are considered. The HERITAGE Family Study found that exercise training increases aerobic fitness regardless of age, gender, race and initial fitness level.41

Why is vigorous exercise better for health?

There are a number of mechanisms that may explain why vigorous exercise is more effective in fighting obesity, type-2 diabetes and coronary heart disease. In all individuals, weight loss occurs when energy expenditure is greater than energy intake.42 Vigorous exercise burns more calories per minute than moderate exercise and, thus, is more effective in controlling weight. Indeed, the International Association for the Study of Obesity concluded that 30 minutes of moderate activity per day was insufficient to prevent unhealthy weight gain.43 Instead, the expert panel concluded that the prevention of weight regain in formerly obese individuals required 60–90 minutes of moderate activity per day or lesser amounts of vigorous activity.43Aerobic exercise increases insulin sensitivity and, thus, helps to lower blood sugar and prevent type-2 diabetes. Interestingly, the ‘insulin-sensitising’ effect of exercise is greater during vigorous exercise than during moderate exercise.44 Indeed, it is likely that exercise must be of sufficient intensity to deplete muscle glycogen before it increases insulin sensitivity.45 Serious swimmers, cyclists and runners routinely engage in high-intensity, glycogen-depleting exercise.

Aerobic exercise lowers blood pressure and improves one’s cholesterol profile for around 24 hours.46,47 The effect of exercise intensity on CHD risk factors is unclear because too few studies have compared moderate- and high-intensity interventions of equal energy cost. However, the available evidence suggests that high-intensity exercise is more effective in increasing cardiorespiratory fitness,13,16 which is a powerful predictor of CHD risk.36,37

Is vigorous exercise dangerous?

The risk of death during exercise is greater than the risk of death at rest. However, the remote risk of death during exercise must be balanced against the real risk of premature death conferred by a lifetime of inactivity. Paul Thompson, an eminent cardiologist, once said, ‘If your only goal is to survive the next hour of your life, you should get into bed – alone. But if your goal is to live a long, healthy life, then get some exercise for the next hour.’In an effort to investigate the frequency of exercise-induced death, Dr. Thompson and colleagues48 collected data on all deaths during jogging in Rhode Island from 1975 to 1980. Ten exercise-related deaths were recorded and it was estimated that there was one death per year for every 7,620 male joggers aged 30 to 65. When victims with known coronary artery disease were excluded, the annual death rate was estimated as 1 per every 15,240 previously healthy joggers. This figure is in agreement with a Seattle study where there was an estimated 1 death per year for every 18,000 physically active men.49

It is likely that Marc-Vivien Foe and Reggie Lewis died of rare congenital heart defects.50 The rarity of exercise-induced deaths does not justify complacency, however. Paul Thompson strongly recommends that coaches and officials learn and update yearly their cardiopulmonary resuscitation skills.51 Dr. Thompson also recommends that any person, young or old, who experiences possible cardiac symptoms during exercise, should undergo a cardiac evaluation prior to returning to training or competition.51 A review of the symptoms that warn of coronary abnormalities is beyond the scope of this article and the reader is referred elsewhere.51 This said, exercise-induced chest discomfort, dizziness and fainting should not be ignored.51 Tragically, Jim Fixx ran through chest pain and chest discomfort.52

Conclusion

Athletes should carry on ignoring current physical activity guidelines: they weren’t written for the serious exerciser! Thirty minutes of moderate activity per day might bring about some improvement in the health of the nation, but it’ll do little for your 10K time and won’t minimise your risk of a premature death. Vigorous exercise maximises cardiorespiratory fitness and maximises your chances of living a long, healthy life. Keep up the good work!References

- WHO Mortality Database. Available at: www3.who.int/whosis/menu.cfm?path=whosis,mort&language=english.

- Circulation. 2004;109:1101-7.

- Coronary heart disease statistics. London: British Heart Foundation; 2004.

- Am J Med. 1988;84:739-49.

- Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1978;10:vii-x.

- Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1990;22:265-274.

- Allied Dunbar National Fitness Survey. 1992.

- JAMA. 1995;273:402-7.

- Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30:975-991.

- Am J Prev Med. 1999;17:24-30.

- Department of Health: At least five a week: evidence on the impact of physical activity and its relationship to health. Available at: www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/08/09/81/04080981.pdf.

- Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1996;28:706-19.

- J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:1619-25.

- J Appl Physiol. 1997;82:270-7.

- Am J Cardiol. 1986;57:446-9.

- N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1483-92.

- Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1995;19 Suppl 3:S37-45.

- Lancet. 1980;2:1207-10.

- Lancet. 1973;1:333-9.

- JAMA. 1995;273:1179-84.

- Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:293-9.

- Prev Med. 2001;29:37-52.

- JAMA. 2002;288:1994-2000.

- JAMA. 1989;262:2395-2401.

- US Armed Forces Medical Journal. 1959;10:675-688.

- JAMA. 1996;276:205-10.

- JAMA. 1995;273:1093-8.

- N Engl J Med. 1991;325:147-152.

- Lancet. 1991;338:774-8.

- Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:89-96.

- Am Heart J. 1976;92:39-46.

- Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993;25:71-80.

- Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:754-761.

- N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1035-41.

- Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2285-94.

- GAm J Cardiol. 2000;86:53-8.

- N Engl J Med. 2002;346:793-801.

- JAMA. 1989;261:3590-3598.

- J Intern Med. 1992;232:471-9.

- JAMA. 1998;279:440-4.

- J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:1770-6.

- National Audit Office. Tackling Obesity in England. 2001.

- Obes Rev. 2003;4:101-14.

- Diabetes Care. 1996;19:341-9.

- N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1357-62.

- Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36:533-53.

- Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:S438-45.

- JAMA. 1982;247:2535-8.

- N Engl J Med. 1984;311:874-877.

- Pediatr Med Chir. 1998;20:101-3.

- Thompson PD. The cardiovascular risks of exercise. In: Thompson PD, ed. Exercise & Sports Cardiology. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001:127-145.

- Res Q Exerc Sport. 2002;73:38-46.

- Public Health Rep. 1985;100:126-31.

- Sports Med. 1986;3:346-356.

- Bouchard C, Shephard RJ. Physical activity, fitness and health: the model and key concepts. In: Bouchard C, Shephard RJ, Stephens T, eds. Physical activity, Fitness and Health: International proceedings and consensus statement. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 1994.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity and Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. 1996.

- Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:754-761.

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.