Omega-3: a fat lot of good for athletes!

New research suggests that omega-3 oils are even more important for health and performance than previously believed, and that most athletes don’t get anywhere near enough!

Let’s talk about fat – not body fat, but what goes into your mouth. Of all the macro-nutrients (protein, carbohydrate, fat), fat nutrition is easily the most poorly understood. Contrary to popular belief propagated in much of the mainstream media, dietary fat is not necessarily ‘nasty’ and something to be avoided at all costs. Apart from the specific and essential biological functions of the essential fats, some dietary fat in the diet is desirable for a number of reasons:- Firstly, dietary fat tends to make food more palatable in the mouth, and therefore more enjoyable to eat.

- Secondly, fat has a satiating effect; eat a completely fat-free meal and the chances are you’ll be hungry again before you know it.

- Thirdly, at nine calories per gram (over double that of protein and carbohydrate) fat is a concentrated energy source, so is a useful addition to the diet when your daily energy expenditure is very high.

Fat nutrition challenges

The problem with fat nutrition arises not so much with the absolute quantity consumed, but rather when too much of the wrong kinds of fats are consumed (especially processed/chemically altered fats), and not enough of the right kind of fats. When it comes to the latter, this is particularly true when it comes to the essential ‘omega-3’ fats, which are frequently lacking in Western diets(1). This shortfall arises as a result of poor choices – ie not including enough good food sources of omega-3 such as fatty fish and nuts & seeds in the diet. It also is a consequence of the consumption of a significant amount of processed and refined foods, which tend to be low in omega-3 as a result (see box 1 and figure 1 below).Box 1: What is omega-3?

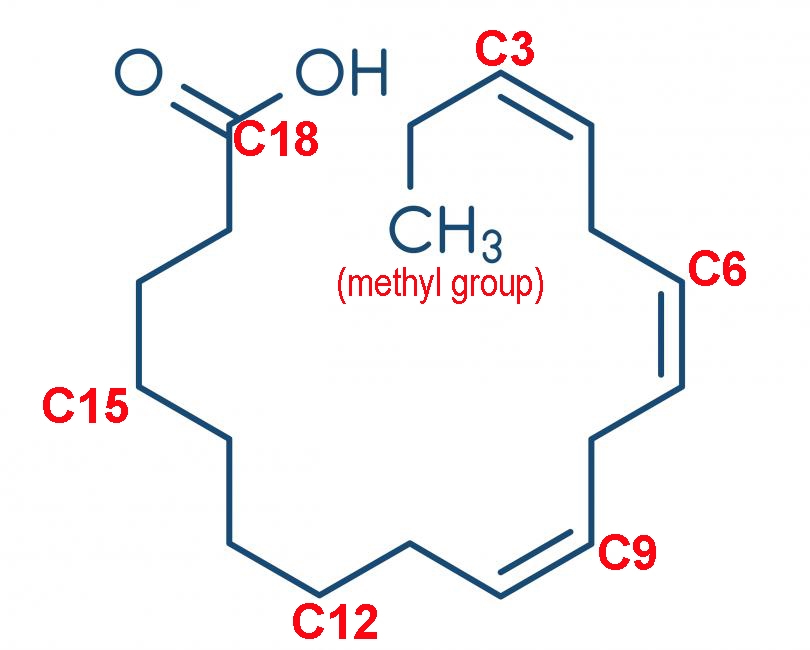

There are two essential fats for human health: alpha-linolenic acid (omega-3) and linoleic acid (omega-6). These two fats are essential, because as well as being absolutely vital to build healthy cell membranes in our bodies, their chemical structure means that they can also be used to make hormone-like substances in the body called prostaglandins, which go on to regulate a host of other functions.Figure 1: Structure of omega-3

Both these essential fats are long chains of 18 carbon atoms, and have either two or three reactive carbon-carbon double bonds positioned along the chain, which is what gives them special biological activity. Figure 1 below shows the chemical structure of omega-3, which has three double bonds on the chain; one positioned next to the third carbon (C3) from the methyl group at the end, a second positioned next to the sixth carbon (C6) and the third positioned at C9. Omega-6 has the same structure except it lacks the C3 double bond. Incidentally, when there is only one carbon-carbon double bond present (at C9), this is oleic acid – the main (monounsaturated) fat present in olive oil.

Human enzyme systems can’t insert carbon-carbon double bonds into positions closer than 7 carbons from the methyl end of the chain. Plants can though and that’s why we rely on getting these two essential fats ‘readymade’ from our diet, rather than make them ourselves. In this article however, we will not focus on omega-6 because 1) unlike omega-3, it is relatively abundant in the diet, and 2) all its biological derivatives can be synthesized from omega 3, whereas omega-3 derivatives cannot be synthesized from omega-6.

The omega-3 challenge

As mentioned above, studies show that omega-3 fats are not well supplied in Western diets. But why is this? Part of the reason is that many people do not regularly consume foods rich in omega-3 such as fatty fish (eg salmon, sardines, mackerel, herring etc), nuts and seeds. At this point, it’s worth clarifying that there are actually three different omega-3 fats:- Alpha-linolenic acid (ALA – figure 1)

- Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA)

- Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)

Regardless of the source however, omega-3 nutrition is complicated by the fact that – thanks to the three carbon-carbon double bonds present - these fats are very chemically reactive. In plain English, they readily undergo chemical change and ‘fall apart’ when exposed to heat, light or air. This means that when you try to store them or when you cook or process foods containing them, not only is some of their nutritional value is lost, they can actually be quite easily degraded into potentially harmful compounds – eg trans fats and fats where part of the molecule has been oxidised/damaged. In addition, we need comparatively large daily amounts of these essential fatty acids compared to any other single nutrient (we’re talking teaspoon, not milligram amounts!), and getting these in an unadulterated form can be a major challenge in today’s world of tinned, dried, frozen, fast and processed foods!

How much omega-3 do you need and what for?

Over the past thirty years or so, robust evidence has accumulated regarding the benefits of omega-3 fats on cardiovascular health. In particular, the benefits of omega 3’s for blood pressure, and blood triglyceride (fat) levels have been clearly documented. There is also evidence that optimum intakes of omega-3 fats help to prevent inflammation (important for athletes - see this article), heart attack, stroke, cardiac arrhythmias, and sudden cardiac death(2).In addition to these benefits, newer research has discovered that omega-3 fats may play a significant ‘neuroporotective’ role in brain tissue, helping to prevent brain tissue damage caused by trauma, and to heal brain tissue when trauma has occurred(3,4). Because of these protective effects, the use of dietary omega-3 to help prevent and treat head trauma sports injures – eg concussion – has evolved into a very active and exciting area of research, and some researchers now believe that athletes who participate in contact sports such as rugby and soccer should play close attention to their omega-3 intake(5).

How much omega-3 is needed for health? This is actually quite an opaque topic. The USDA 2015-2020 guidelines for omega-3 intake for example recommend that Americans consume 8oz of fish per week, which (depending on the type of fish) would typically supply an average daily intake of around 250mgs (a quarter of a gram) per day. In the UK, the British Dietetic Association recommends that adults should try to eat two portions of fish per week, one of which should be oily, to get the most benefit www.bda.uk.com/resource/omega-3.html 2nd July 2021. Meanwhile, the American Heart Association (AHA) recommends 1-2 portions of oily fish per week (approximating to 500mgs per day of EPA/DHA) to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease.

The omega-3 index

Given that the recommendations on optimum omega-3 intake are somewhat vague, and don’t take into account individual variations in metabolism, a better way to assess whether someone is regularly consuming enough omega-3 is to look inside the body. In a landmark 2008 study, Dr William Harris developed what is known as the ‘omega-3 index’ garnered by blood sampling(6). This index shows what percentage of the total amount of fatty acids in red blood cells are EPA and DHA (both of which can be synthesized from ALA). For example, if 6% of the fatty acids in red blood cells are EPA and DHA, the omega-3 index is 6%.Because oily fish and nuts/seeds intake in the West is relatively low, the average omega-3 index is only around 4-5%(7). In countries where a greater amount of fish is consumed, the omega-3 index is higher. For example, the Japanese typically have an index of around 9-10%. Accumulating evidence shows that the index is strongly and inversely associated with cardiovascular outcomes. In other words, individuals with higher indexes tend to have significantly lower cardiovascular risk than individuals with lower indexes. The scientific consensus at the current time is that an omega-3 index of 8% or more is optimal for cardiovascular health, while an index of 4% or lower is typically regarded as a state of dietary omega-3 deficiency, resulting in a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular disease(8).

Athletes and omega-3 intake

At this point, you may be assuming that because you are fit and healthy, and eat pretty well, and are at low risk of cardiovascular disease, athletes needn’t bother about their omega-3 intake or omega-3 index. However, the evidence suggests this is most definitely not the case! For example, research on the dietary habits of North Americans shows that not only is consumption of omega-3 below that recommended(9,10), but also that this sub-optimum intake also extends to athletes and sportsmen/women(11). Indeed, an extensive study conducted by the National Collegiate Athletics Association (NCAA) showed that US collegiate athletes consume well below that recommended amount of omega-3 (500mgs per day) with the average omega-3 intake averaging a shockingly low 100mgs per day(12). This is in stark contrast to updated International Olympic Committee (IOC) recommendation that elite athletes should consume around 2g per day of omega-3 from food sources and supplements(13). In plain English, this means that many athletes, even those training at an elite level may well be consuming as little as one tenth to one twentieth of their optimum omega-3 intake!Omega-3 status in athletes

Given that assessing omega-3 intakes is difficult and that optimum intakes may vary (as discussed above) what evidence is there regarding the omega-3 index scores in athletes? Because the omega-3 index is not widely available as part of routine testing for nutritional status, there’s not a lot of data on this subject. However, that which exists strongly suggests that athletes do NOT generally consume sufficient omega-3 in their diets. For example, a 2014 study found that average values in male and female elite endurance athletes average just under 5% (4.97% to be precise)(14). Remember, the optimum omega-3 index score is 8% or more. In another study on NCAA male football players, 34% of players had levels below 4%, with the remaining 66% averaging between 4% and 8%(15). The average for the group as a whole was just 4.4%, with virtually no players scoring the desired 8+%.Similar results were also found in a wider spectrum of NCAA athletes, with omega-3 index scores averaging around 4.79% in males and 4.75% in females(16). In a much more recent study published last November in the journal Nutrients, researchers examined both the omega-3 intakes and the omega-3 indexes of elite Canadian rugby players(17). This study also looked at the supplement intakes of the players to see what impact any omega-3 supplementation produced compared to players not taking supplements.

Rugby players and omega-3

In the study, researchers investigated the dietary intakes (food plus supplements) of 34 rugby players (19 male and 15 female), specifically to determine their omega-3 intakes. The dietary intakes were assessed using a food frequency questionnaire, which asked about intake of foods high in omega-3, including fish and other seafood, walnuts, flaxseed, flaxseed oil, cod liver oil and canola oil consumption. For each food, players reported the frequency of consumption over the past six months - from ‘never’ to ‘several times a month, week or day’. If the food was consumed, participants then recorded the average portion size consumed based on sex-specific portion size from small to large listed in ounces for fish and seafood, cups for walnuts, and teaspoons for oils and flaxseed.The results showed that just two of the 34 players (both female) attained the desirable 8+% score on the omega-3 index (see figure 2). Overall, the players averaged a score of just 4.54%. Given the cardiovascular benefits of omega-3 and the potential protection it can offer against head trauma injuries, these findings are far from ideal. And while the scores in the omega-3 supplemented players were slightly higher compared to the unsupplemented players (4.82% vs. 3.94% respectively), the impact of supplementation was fairly minimal; the proportion of supplemented players in the high-risk category was still 39.1% compared to 45.5% in the unsupplemented players (see table 1). This suggests that while it can help, omega-3 supplementation is a less effective strategy for optimizing omega-3 intake than eating plenty of omega-3 rich foods in the first place!

Figure 2: Omega-3 index scores by sex(17)

Each dot represents a player. Only two (female) players scored over 8% in the omega-3 index testing. The average score is shown by the thicker black horizontal lines.

Table 1: Omega-3 deficiency risk category by supplementation status(17)

Supplementation made a relatively small impact on the players’ risk categories.

Recommendations for athletes

As we’ve observed in previous articles on the dietary habits of athletes, sub-optimum nutrient intakes and even outright deficiencies are surprisingly common in certain groups of athletes – for example, iron nutrition in female athletes. However, the latest and best data on omega-3 nutrition and omega-3 status in athletes suggests that sub-optimum intakes are far more common than for most other nutrients. In fact, so common are these low intakes that you should automatically assume your omega-3 intake is probably NOT enough, unless that is you’ve had an omega-3 index test carried out to prove the contrary.The data also shows that although it helps to a degree, simply taking fish oil supplements to top up your omega-3 intake is unlikely to be a substitute for consuming plenty of omega-3 rich foods as part of your day-to-day diet. In addition to consuming plenty of omega-3, it’s also recommended that your intake of processed and adulterated oils and fats is kept to a minimum; remember the goal is to tip the ratio of fat intake towards omega-3! With that in mind, below is a comprehensive checklist of how to improve your omega-3 status, and seriously boost your health!

Boosting omega-3 intake

- Use fresh seeds sprinkled on salads, especially hemp, pumpkin and sunflower.

- Use nuts in salads or mixed with raisins as snacks, especially walnuts, pecans and hazelnuts.

- Switch to wholemeal bread – the wheat germ in whole wheat is a good source of EFAs.

- Eat whole grain breakfast cereals such as Shredded Wheat, Weetabix and oat flakes rather than refined cereals such as cornflakes and rice crispies. Whole grains are good sources of EFAs.

- Likewise, use whole brown rice and wholemeal pasta instead of white varieties (the germ contains EFA).

- If you can, use a cold-pressed seed oil in salad dressings (flax seed and olive blended makes a tasty combination), but make sure that it is fresh, has been packaged in a container that is also opaque to light and that the oil has been kept refrigerated since being produced.

- Add a dessertspoon of flax seed oil to protein shakes and recovery drinks (use a blender). Good quality flax seed oil has a subtle nutty taste, which most people find very pleasant!

- Eat fatty fish twice a week; the omega-3 oils in fish are especially beneficial for health. If you can get fresh mackerel, herring, sardines or unfarmed salmon and trout, so much the better – these will be free of chemical residues.

- Don’t rely too heavily on low fat/diet foods and protein/carbohydrate shakes for your calories – these are nearly all devoid of EFAs.

- Go for free range chicken and wild meats where possible – these generally contain higher amounts of EFAs than their intensively reared counterparts.

- Similarly, go for real free-range eggs if you can get them. Free foraging hens fed on natural foods lay eggs containing up to 30% of the fat as EFAs.

Reducing processed and chemically adulterated oils

- Use butter for spreading, NOT margarines - even low-fat, polyunsaturated or cholesterol-lowering margarines. These products are often high in adulterated fats. Forget ‘easy spread’ butters too – they often have hydrogenated vegetable oils added to make them ‘spreadable’.

- Use only pure olive oil or butter for cooking – not sunflower, corn oil or any other vegetable oil. While not a good source of EFAs, olive oil and butter are relatively heat stable and do not produce potentially harmful compounds when heated.

- Avoid as much as possible the following (even low-fat versions), which all contain adulterated (and potentially) harmful fats when produced commercially: crisps, biscuits, cakes, pastries, crackers, confectionery, chocolate (plain dark high-cocoa solid varieties are okay), pies, frozen or prepared meals, mayonnaises, salad dressings, chips, processed meats, ‘cook in’ sauces and curry pastes.

- Avoid ANY products containing ‘hydrogenated vegetable oil’. Check all labels – you’ll be surprised where they pop up!

- For baking or treats, use butter or cream.

- Lipid Res. 2016;63:132–152. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2016.05.001

- Front Nutr. 2022 Feb 3;9:809311. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.809311. eCollection 2022

- Neurotrauma. 2010;27:1617–1624

- 2011;68:474–481

- Sports Med. 2018;48:39–52

- Am J Clin Nutr. 2008 Jun;87(6):1997S-2002S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.6.1997S

- Am J Clin Nutr. 2011 May;93(5):950-62. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.006643

- 2021 Jan 12;13(1):204. doi: 10.3390/nu13010204

- Lipid Res. 2016;63:132–152

- J. 2014;13:1–6. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-13-31

- PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0228834

- J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2016;26:497–505

- J. Sports Med. 2018;52:439–455

- J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2014;24:559–564

- Athl. Train. 2019;54:7–11

- J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2016;26:497–505

- 2021 Oct 25;13(11):3777

You need to be logged in to continue reading.

Please register for limited access or take a 30-day risk-free trial of Sports Performance Bulletin to experience the full benefits of a subscription. TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.