Core strength for injury prevention: go Pilates?

Could Pilates training to improve core stability help athletes with chronic or recurrent back pain? SPB looks at new research

If you’ve never suffered from low back pain, consider yourself lucky. Around 4 out of 5 adults will experience back pain at some point in their life, with many suffering from recurring episodes. This all comes at a cost; in the UK alone for example, this is estimated at several £billion per year through loss of productivity and absenteeism from work. For athletes such as soccer and rugby players, runners and cyclists, the cost is in missed training days, missed competitions, and generally getting frustrated. After all, while you can ‘train around’ other injuries, a back injury is very debilitating, and light activity and movement is about all you can manage!Back problem and core muscle activation

The onset of back pain is often multi-factorial. A single episode of back pain can be precipitated by unusually heavy loading, often combined with unaccustomed movement such as twisting. However, those who suffer from repeated episodes of back pain with little or no obvious cause are more likely to have some kind of movement dysfunction and/or muscle imbalance/weakness, particularly involving the trunk muscles that control spine movement.Deep core muscles lying close to the spine (local muscles) are essential for stabilizing the spine while the larger muscles (often referred to as ‘global’ muscles) contract to perform movements. These deep stabilizing muscles include the deep traversus abdominis of the frontal trunk and the multifidus muscles of the lower back (see figure 1). Research shows that ‘proximal stabilization’ of the spine by the local muscles is essential for accomplishing functional tasks while preventing excessive loads on the vertebrae during movements initiated by the global muscles(1,2).

Research also shows that movements of the limbs without adequate proximal stabilization can stress the spine and soft tissues, resulting in abnormal functions of balance and posture control, which increase the risk of injury(3,4). Furthermore, studies on patients with lower back pain due to spinal instability have identified local muscle weakness and functional disabilities(5), and it is also known that over-activation of the global muscles without adequate core strength can overload the spine and cause pain(6).

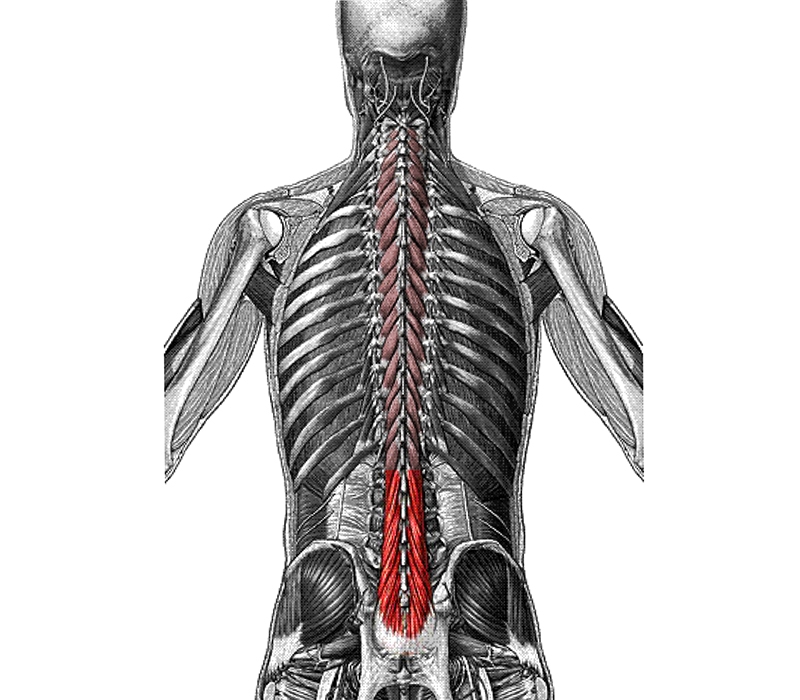

Figure 1: Location of the core-stabilizing multifidus muscles in the trunk

The lumbar multifidus muscles run deep to the lumbar spine and are shown highlighted in red.

Athletes are not immune

Despite often having excellent global musculature – eg strong pectoral, deltoid and latisimus muscles of the chest, shoulder and back respectively – athletes may not possess the core muscle strength and performance to match, which can lead to increased risk of back pain. A 2017 review study, a study that pools the all data from previous studies, looked at the incidence of back in cyclists – a group of athletes that you might (incorrectly) imagine rarely suffers from back pain(7) The researchers sought to establish what relationships existed between body positioning, spinal movement, and muscle activity in active cyclists with chronic lower back pain. Pooling the data from eight studies, the researchers found that increased lumbosacral flexion angle (forward bending) as a result of low handlebar height was a factor in low-back pain. However, the data also showed that core-muscle activation imbalances, and back extensor endurance deficits were much more significant in determining whether cyclists were likely to suffer from low-back pain.Similar findings have been observed in runners. A 2018 study looked at the consequences of running with core muscle weakness(8). It found that core muscle weakness increased peak anterior shear loading (where one vertebra moves horizontally relative to its neighbour) on all the lumbar vertebrae of the spine by nearly 20%. Additionally, compressive spinal loading increased on the upper lumbar vertebrae by up to 15%. The conclusion was that this increased spinal loading over numerous gait cycles can result in damage to spinal structures, and that as a consequence, insufficient strength of the deep core musculature may increase a runner's risk of developing low back pain.

Core strengthening strategies

Given that there are a number of core strengthening exercises that can be performed to increase core stability, it is hardly surprising that these exercises have become popular among athletes and sedentary folk alike who are prone to back pain – for example, see this article. One method of core training that has gained popularity in recent years is Pilates training. Pilates training focuses on the core muscles, emphasizing breathing, concentration, precision and control. Advocates of Pilates training claim that this approach enables superior activation of the core (local) muscles, and critically, core activation before the global muscles are activated, thus being particularly useful for those with chronic or recurrent back pain.Research does indeed lend credence to these claims. Studies show that Pilates breathing can induce the activation of trunk stabilizers helping to properly arrange the firing patterns of muscle recruitment (local first then global)(2). Also, one of the central postures key to Pilates training is with a slightly posterior tilted pelvis that activates the abdominal local muscles while maintaining the neutral position of the pelvis(9). Centralization is one of the basic principles of Pilates, which highlights the active use of the trunk local muscles, and is applied to all Pilates exercises(10). Perhaps unsurprisingly, clinical experts have recently begun to recommend Pilates as a therapeutic exercise approach to rehabilitate disorders of the spine, such as back pain and scoliosis(11,12). And now, brand new research published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health suggests that Pilates could be an especially effective method of core training(13).

The research

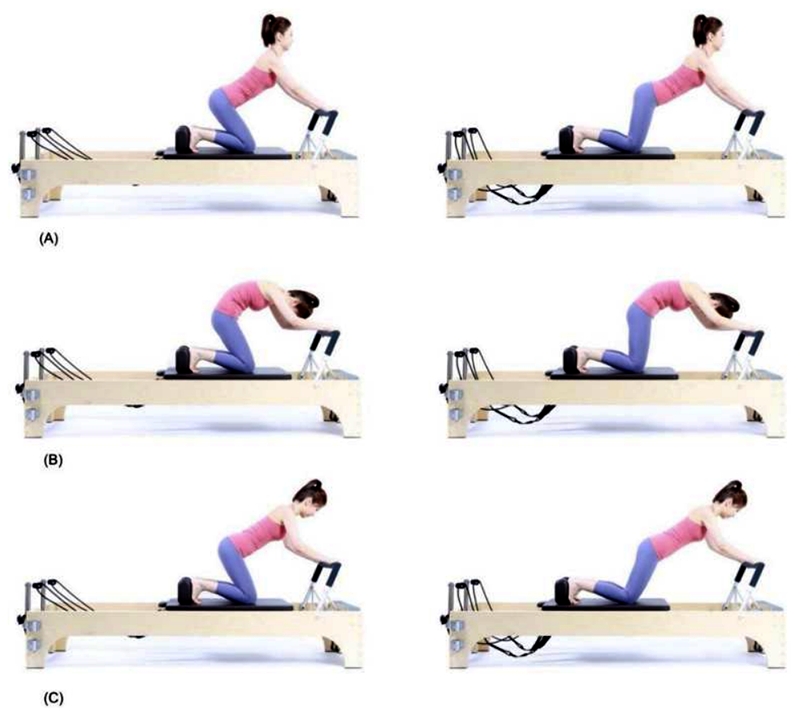

This study aimed to compare the subjects with and without a Pilates training background to find out the effect of previous Pilates training on the core muscle activity and muscle co-contraction, and to examine the relationship between the core muscle activation level and movement patterns. Thirty two female participants were recruited: 16 active, healthy Pilates practitioners with at least one year’s training background and 16 age matched active healthy women with no Pilates experience. None of the subjects had back pain, or a previous history of back pain.All the subjects performed three knee stretches on a piece of equipment often used in Pilates training known as a ‘reformer’. During these exercise, muscle activation was assessed using electromyography (measurement of electrical activity using pads placed at various locations on the trunk). These stretches were performed in three different positions (see figure 1):

- Flat back with a neutral pelvis

- Round back with posteriorly tilted pelvis

- Extended back anteriorly tilted pelvis (EAP)

Figure 1: Knee stretch exercise performed in three different positions

(A) Starting position (left) and end position (right) of the extended back with an anteriorly tilted pelvis (EAP) position. (B) Starting position (left) and end position (right) of the round back with a posteriorly tilted pelvis (RPP) position. (C) Starting position (left) and end position (right) of the flat back with a neutral pelvis (FNP) position.

The findings

What they found was as follows:- Compared to the non-experienced subjects, the Pilates-experienced subjects activated the deeper internal obliques more than the rectus abdominis (the ‘six-pack’ you see in athletes with well toned physiques). This difference between groups was most apparent when the knee slide exercise was performed with a rounded back/posteriorly tilted pelvis - ie during (B) in figure 2.

- The experienced Pilates practitioners activated their deep multifidus muscles (figure 1) more often than the more surface lumbar erector spinae muscles (also known as back extensors). Once again, the most significant difference was observed in rounded back position (B).

- The movement pattern data and combined with muscle activity data showed that the experienced Pilates practitioners activated the abdominal and low back core muscles effectively, and the stability of the pelvis and trunk were better than that of the non-experienced participants.

Implications for athletes

In a nutshell, the researchers concluded that because the experienced subjects were trained to activate local muscles through breathing techniques and proximal stabilization during movements, they seemed to recruit local muscles more readily and use them as stabilizers more efficiently. Although the subjects in this study were not trained athletes per se, the findings have implications for anyone who is physically active since we all share the same basic anatomy and rely on the optimum muscle recruitments patterns to safely perform activity without excessive loading on the spine. And if you are someone who has suffered recurring back pain episodes, these findings are especially interesting.These findings also fit with previous research on this topic; in a 2017 study Pilates-experienced subjects had much higher deep tummy muscle (tranversus abdominis and internal obliques) activations than their target level(14), while other studies have found that Pilates-trained subjects have increased deep abdominal (core) muscle thickness, which is better able to exert a stabilizing force(15,16). This probably explains why data shows that Pilates can increased muscle thickness of the multifidus and abdominal core muscles in those with back conditions, thus reducing pain and improving the overall quality of life(11).

In practice

Athletes with history of chronic or recurring back pain who would like try some Pilates training will find lots of options. There are a number of good books and DVDs that can serve as an introduction. There are also several online tutorials, many of which are free. However, because the key to successful Pilates training is control and precision of movement, those with no previous Pilates background may find the guidance of an experienced instructor is invaluable in the beginning for picking up the fundamentals.Remember too that Pilates isn’t an either/or option; a few Pilates sessions can be blended into an overall core strength program, or even a few Pilates exercises singled out for inclusion. One tip though; the need for precision and control means that Pilates sessions are best performed when you’re relatively fresh. Tacking on a few Pilates exercises at the end of blockbuster strength session is certainly not going to produce the best results!

References

- Curr Sports Med Rep. 2008 Feb; 7(1):39-44

- J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2015 Jan; 19(1):57-61

- J Spinal Disord. 1998 Feb; 11(1):46-56

- Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996 Nov 15; 21(22):2640-50

- Gait Posture. 2018 Mar; 61():375-381

- Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012 Jun 1; 37(13):1101-8

- Sports Health. 2017 Jan/Feb;9(1):75-79

- J Biomech. 2018 Jan 23;67:98-105

- Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008 Nov; 89(11):2205-12

- Bodyw Mov Ther. 2013 Apr; 17(2):185-91

- J Orthop Sci. 2021 Nov; 26(6):979-985

- J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2021 Jul; 27():294-299

- Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Dec; 18(23): 12804

- J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2018 Apr; 22(2):467-470

- J Exerc Rehabil. 2015 Jun; 11(3):161-8

- Complement Ther Med. 2018 Oct; 40():61-63

You need to be logged in to continue reading.

Please register for limited access or take a 30-day risk-free trial of Sports Performance Bulletin to experience the full benefits of a subscription. TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.