You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Female athlete injuries: are ladies really the weaker sex?

Female athletes suffer more sports injuries than their male counterparts. Jason Tee explains why but discovers some surprising facts that turn the female frailty narrative on its head

The times are changing for women’s sport. Once treated as merely a curtain-raiser to the main event, women’s sport has taken significant strides forward in recent years. Women’s sport now boasts many professional leagues with large numbers of viewers and high marketability. As a demonstration of the appeal of women’s sports, an incredible 1.12 billion people watched the most recent women’s soccer world cup(1). Despite a steadily increasing number of spectators across various sports, salaries, prize money, and support services for sportswomen still substantially lag their male counterparts. The total prize money for the FIFA women’s world cup in 2019 was $30 million, while the equivalent men’s event in 2018 paid out $400 million(2).Another significant disparity in male and female sportspeople is their susceptibility to injury (see figure 1). Female sports participants are more susceptible to sporting injury than males. For example, the prevalence of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries in females are 1 in 29, while in males, it is 1 in 50 – an increased risk of approximately 70%(3). The consequences of ACL injury can be tragic. The recovery and rehabilitation process is arduous and often causes younger athletes to miss critical selection opportunities or drop out altogether. An ACL injury can hasten the development of osteoarthritis and thus impact the long-term functionality of an athlete. Therefore, females carry a disproportionate life-long injury burden compared to males.

Similarly, ankle sprain injuries occur almost twice as often in female athletes as males(4). Even more concerning, the concussion rate among athletes is two times higher in women than men(5). Tragically, these concussions tend to be more severe in females than males(6). It seems that being a female sports participant is a dangerous occupation!

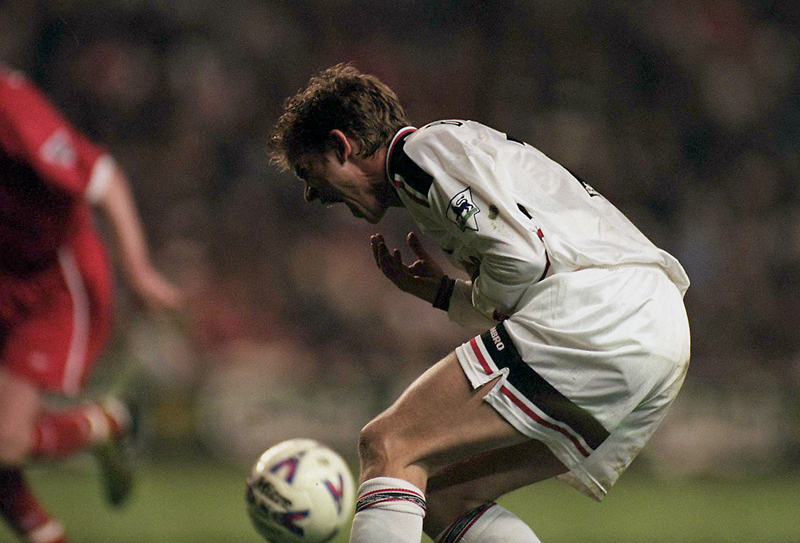

FIGURE 1: COMMON SITES OF INJURY IN FEMALE ATHLETES

Women are more likely to suffer from a sports injury than men.

UNDERSTANDING INJURY RATES AND OCCURRENCE

Why do injuries occur so much more frequently in female sports? One often-cited explanation is the ‘female frailty’ narrative. This theory suggests that female bodies can’t cope with sport’s physical demands because of differences in strength and physiology. As an example, one of the explanations provided for the female propensity for ACL injuries is that females generally have wider hips and larger Q-Angles at the knee, placing them at a mechanical disadvantage during landings (see figure 2)(7).Some also suggest that women are more susceptible to concussion because they have weaker neck muscles than men(8). Therefore, they have less absolute strength to manage and decelerate head impacts and avoid concussion(8). These explanations seem plausible (particularly if you buy into the female frailty narrative), but these explanations are also overly simple and ignore other important determinants of the problem.

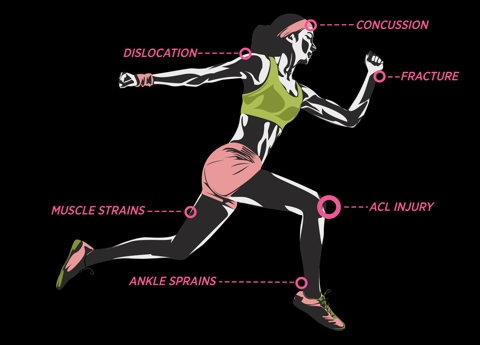

FIGURE 2: DIFFERENCE BETWEEN MALE AND FEMALE Q-ANGLES

Some suggest that skeletal differences make women more prone to injuries such as ACL tears.

Despite the skeletal differences, regular exposure to strength and plyometric training reduces ACL injury risk in females to levels similar to males(9)! In the same way, strength training interventions are very effective at improving neck strength(10). In fact, neuromuscular training interventions effectively reduce all sports injuries in females(11,12). These interventions are typically short duration (10-15 minutes), bodyweight strength and movement skill training programs that easily fit into a sports warm-up routine. Why does the addition of such a small amount of training make such a big difference to injury outcomes?

Strength training adaptations are known to be subject to diminishing returns(13). In other words, individuals with no previous exposure to strength training make bigger gains in a shorter amount of time with the same exercise dose than those with more training experience. If female athletes receive such benefit from relatively small additional exercise loads, they suffer from chronic under-loading during training. Maybe the high rates of injury among female athletes is not the result of female frailty. Instead, perhaps the sports development systems fail to prepare them for the sport’s demands adequately.

PREPARATION IS KEY

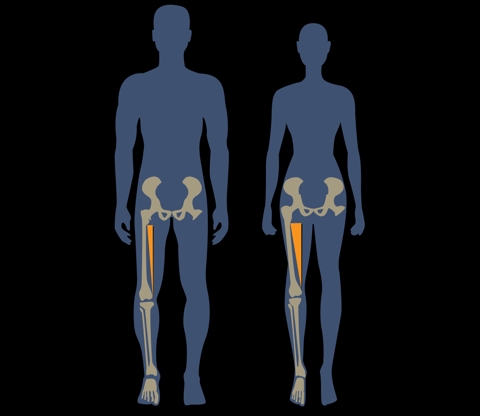

A typical athletic development pathway looks different for a young male versus a young female. An interesting case study to illustrate this point is the English football talent development system (see figure 3). The Football Association (FA) established the first women’s professional football league in 1991. Therefore, women have played professional football in England for almost 20 years.To feed this system, the association encourages promising female youth players to join one of 34 Regional Talent Clubs that offer a minimum of three hours of training per week. In comparison, there are currently 85 full-time academies that provide up to 12 hours of professional training per week for male players. Is it any wonder that female footballers are more susceptible to injury? They receive a fraction of the training and preparation that their male counterparts receive.

FIGURE 3: FOOTBALL ASSOCIATION GIRLS’ ENGLAND TALENT PATHWAY

It’s time to throw out the female frailty narrative in sports. Female physiology is different from that of males, but not inferior. If you correct for body size, men and women display very similar strength and endurance capabilities(14). The predominant sex hormones – testosterone and estrogen – primarily mediate the differences in performance capacities between sexes. Due to the hormones’ influence, males tend to have a greater overall muscle mass, while females tend to retain a greater percentage of body fat. In addition, men tend to have longer bones, which creates a mechanical advantage in some sports. The net result of these factors is, females demonstrate about 66% of a weight-matched male counterpart’s strength. This difference is smaller in highly trained individuals, with an approximate 10% difference in world record performances for males and females in running and swimming.

Even without correcting for body size, women display a sporting advantage over men. They are more resilient to fatigue than males, and as a result, recover faster. In a study where both men and women performed a 1-rep max lift 20 times, the men’s performance decreased by 28% over the exercise session, while the women’s deteriorated by only 19%(15). In addition, the female participants showed lower levels of residual fatigue 1 hour after the training session than the males did(15). This female resistance to fatigue has also been demonstrated in long-distance running, where female runners do not slow down as much as male running in the second half of marathon races(16).

When considering injury prevention in female sport, it’s important to think about the phenomenon of female resistance to fatigue. The presence of residual fatigue from training is a known risk factor for sports injury(17). Given equal preparation and training, female athletes should be less susceptible to injuries than males because they fatigue more slowly and recover faster!

The female frailty narrative is damaging for female sports participants at all levels. It’s presence allows coaches and athlete service providers a convenient excuse when an injury occurs. This justification stops them from further investigating the reasons for the injury and taking steps to rectify these problems. Being female should not be an injury risk factor in the 21st century.

Female athletes aren’t physiologically inferior, but the services provided for them and the development processes available to them may well be. It’s time to stop accepting the high frequency of female sports injury as inevitable and start challenging the system that causes it. Our daughters deserve access to all the benefits that come with a lifelong involvement in physical activity without having to fear the long term consequences of injury.

One of the first sports to recognize and address the gender gap was tennis. In 1974, Billie Jean King threatened to boycott the US Open if men and women weren’t offered equal prize money. Today, tennis is one of the fairest sports in terms of pay, with female players earning 80% of what males earn. Within this (almost equitable) environment, Serena Williams emerged to become the best tennis player in history. Serena has won more Grand Slams than any other player, male or female. Given an even payment playing field, female athletes have better resources to secure more training time, equipment, and personnel. With better preparation and training, girls might just rule the sports world.

REFERENCES

- www.fifa.com/womensworldcup/news/fifa-women-s-world-cup-2019tm-watched-by-more-than-1-billion

- www.cnbc.com/2019/06/07/the-2019-womens-world-cup-prize-money-is-30-million.html

- Br J Sports Med. 2019 Aug;53(16):1003-1012.doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096274

- Sports Med. 2014 Jan;44(1):123-40.doi: 10.1007/s40279-013-0102-5.

- Sports Health. Nov/Dec 2019;11(6):486-491.doi: 10.1177/1941738119877186.

- Br J Sports Med. 2009 May;43 Suppl 1:i46-50.doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.058172.

- Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002 Aug;(401):162-9.

- J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2019 Nov;49(11):779-786.doi: 10.2519/jospt.2019.8760.

- Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010 Jun;18(6):824-30.doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-0901-2.

- Sports Med. 2016 Aug;46(8):1111-24.doi: 10.1007/s40279-016-0490-4.

- Br J Sports Med. 2013 Aug;47(12):794-802. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091886.

- BMJ. 2012 May 3;344:e3042.doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3042.

- J Strength Cond Res. 2005 Nov;19(4):950-8.doi: 10.1519/R-16874.1.

- Sports Med. Sep-Oct 1986;3(5):357-69.

- Int J Sports Med. 1993 Feb;14(2):53-9.doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1021146.

- Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015 Mar;47(3):607-16.doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000000432.

- Br J Sports Med. 2017 Mar;51(5):428-435.doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096040.

About Jason Tee

Jason Tee is a Strength and Conditioning coach and researcher in athletic performance, focusing on injury reduction and training prescription, particularly in rugby union players. Prior to his career as a university lecturer, Jason spent 12 years working as a coach within youth and development sportNewsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.