You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Transgender women in female sport: why biology matters

Do transgender women competing in the female category of sport enjoy a biological advantage, and what are the implications for female sport?

Here’s a statement of fact: males enjoy significant physical performance advantages over females within competitive sport. This is because sporting performance is strongly influenced by a range of physiological factors, including muscle force and power-producing capacity, size characteristics, cardiorespiratory capacity and numerous metabolic factors. Many of these physiological factors differ significantly between biological males and females (see table 1)(1-7).Table 1: Selected physical differences between untrained/moderately trained males and females (female levels are set as the reference value)(1-7)

Variable |

Magnitude of sex difference (%) |

| Lean body mass | +45 |

| Body fat% | −30 |

| Muscle mass lower body | +33 |

| Muscle mass upper body | +40 |

| Grip strength | +57 |

| Knee extension peak torque | +54 |

| Tendon tensile force | +83 |

| Tendon stiffness | +41 |

| Absolute oxygen uptake values | +50 |

| Relative oxygen uptake values | +25 |

| Lung ventilation (maximal) | +48 |

| Cardiac output (maximal) | +30 |

| Cardiac stroke volume (maximal) | +34 |

| Blood hemoglobin concentration | +11 |

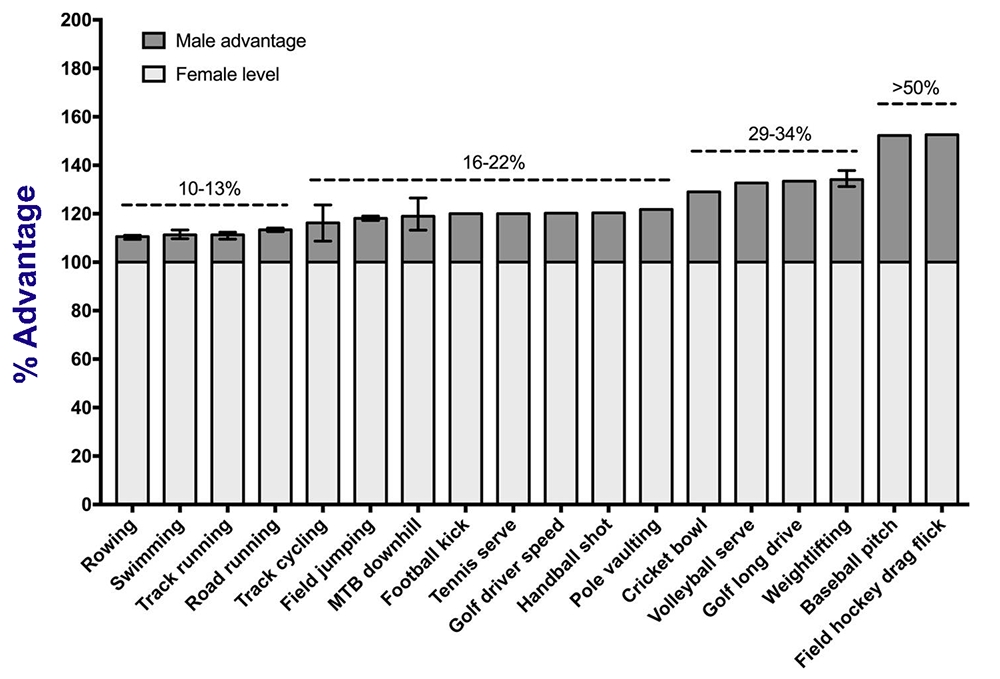

These differences arise as a result of genetic differences between biological males and females, and the hormonal-directed development of secondary sex characteristics – eg secretion of testosterone in males and estrogen in females(8,9). Taken together, the differences confer large sporting performance advantages in terms of physiology for biological males over females(10). The significance of the sporting advantage can be seen in figure 1, which shows for a range of sports, the performance advantage (some 10-50%) conferred by biology that male elite athletes enjoy over their female elite equivalents.

The male performance advantage over females across various selected sporting disciplines(10)

Notes: Female achievement level is set to 100%. In sport events with multiple disciplines, the male value has been averaged across disciplines, and the error bars represent the range of the advantage. Data shown compiled from publicly available sports federation databases and/or tournament/competition records. MTB = mountain bike.

Female and male sports categories

Broadly speaking, males are bigger and stronger than females - thanks to the superior physical capacity developed during puberty in response to testosterone - and enjoy significant performance advantages over females. It has been argued that this performance divergence has been compounded historically by poor cultural acceptance of, and financial provision for, females in sport, which in turn slowed the rate of improvement in athletic performance in females. However, since the 1990s, the difference in performance records between males and females has been relatively stable, suggesting that biological differences created by sex hormones during puberty actually explain most of the male advantage(11,12).When comparing athletes who compete directly against one another, such as elite or same-aged school athletes, the performance data strongly suggests that the physiological advantages conferred by biological sex are insurmountable. Furthermore, in sports where contact, collision or combat are an important component of games, the widely different physiological attributes between males and females may lead to serious safety and athlete welfare concerns for females. Therefore, to ensure that both men and women can enjoy sport in terms of fairness, safety and inclusivity, most sports are divided (in the first instance) into male and female categories.

The transgender dilemma

The traditional sex-based segregation into male and female sporting categories does not account for transgender persons who experience incongruence between their biological sex and their experienced gender identity. In particular, the issue of transgender women (born biologically male but subsequently identifying as women) wishing to compete in the female category has come to the fore, with concerns about fairness and safety within female competition, and discussion about how to fairly and safely accommodate transgender persons in sport.The current International Olympic Committee (IOC) policy on transgender athletes states: ‘it is necessary to ensure insofar as possible that trans-athletes are not excluded from the opportunity to participate in sporting competition’. But the policy also states: ‘the overriding sporting objective is and remains the guarantee of fair competition’. However, if male performance advantages (conferred by being born biologically male) are carried through to competition in the female category, an obvious question surrounding transgender women competing in sport arises - are these two goals conflicting?

To try and square the circle, the IOC determined criteria by which transgender women may be eligible to compete in the female category of sports. These include a solemn declaration that the athlete’s gender identity is female and the maintenance of total serum testosterone levels below 10nmol/L (achieved via testosterone-suppressing drugs) for at least 12 months prior to competing and during competition(13). The limit of a 12-month testosterone level below 10nmol/L was set by the IOC in the belief that this testosterone criterion is sufficient to reduce the sporting advantages of biological males over females and deliver fair and safe competition within the female category. However, new research suggests this might be far from the actual reality.

New research

In a newly published paper titled ‘Transgender Women in the Female Category of Sport: Perspectives on Testosterone Suppression and Performance Advantage’ researchers from Sweden and the UK have investigated the longitudinal effects of testosterone-suppression therapy on the physiological characteristics of transgender women to establish whether such a course a therapy does indeed level the playing field between biological female athletes and transgender female athletes, thus allowing fair and equitable competition(14).In order to establish the actual effects of testosterone-suppression therapy on transgender women in sport, the data from twelve longitudinal studies (where the subjects were tracked over a period of time) was analyzed to examine the effects on the subjects’ lean body mass or muscle size. These studies typically used a very accurate method of determining muscle mass, lean body mass, and muscle volume or cross-sectional area known as ‘Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry’ (DEXA). In these studies, subjects were tracked for between one and three years, with measurements taken at a number of time points throughout the monitoring period.

What they found

The key findings were as follows:- All the studies found very consistent changes in lean body mass after 12 months of treatment.

- The change (reduction) in lean body mass averaged between -3% and -5% after 12 months of testosterone suppression therapy.

- The subjects tended to have slightly greater reductions in arm muscle mass compared with the leg region.

- The duration of the testosterone-suppression therapy did not significantly affect the magnitude of muscle mass loss – ie there were no greater losses at three years compared to one year.

- The reductions in muscle mass (averaging around 5%) after testosterone-suppressing therapy were small compared to the relative initial superior mass conferred to the transgender women as a result of being born biologically male (typically around +40% compared to athletes born biologically female).

Understanding the data

The researchers questioned the IOC criteria outlined above and concluded that ‘the muscle mass advantage males possess over females, and the performance implications thereof, are not removed by one to three years of testosterone suppression in transgender women’. They also concluded that ‘in sports where muscle mass is important for performance, inclusion is therefore only possible if a large imbalance in fairness, and potentially safety in some sports, is to be tolerated’.The researchers did acknowledge that the longitudinal studies analyzed examined the lean muscle mass changes in non-athletic transgender women with relatively low activity levels - not athletes – and therefore more research is needed. However, they advanced three possibilities that might be expected in that research:

- The first possibility is that athletic transgender women will experience similar reductions (approximately − 5%) in muscle mass and strength as untrained transgender women, and will thus retain significant advantages over a comparable group of females.

- A second possibility is that by virtue of greater muscle mass and strength at baseline, pre-trained transgender women will experience larger relative decreases in muscle mass and strength particularly if training is halted during transition – ie resulting in smaller advantages.

- A third option is that training before and during the period of testosterone suppression may attenuate reductions in muscle mass so that that relative decreases in muscle mass and strength will be very small or non-existent in transgender women who undergo training, thus conferring an even bigger advantage

Conclusion

As the researchers reported, the reductions observed in muscle mass, size, and strength were very small compared to the baseline differences between males and females in these variables, which suggests major performance and safety implications in sports where these attributes are competitively significant. Moreover, the data also undermines the delivery of fairness and safety set out in transgender inclusion policies, particularly given the stated prioritization of fairness as an overriding objective (for the IOC). There’s another issue at play here too: if testosterone suppression therapy doesn’t equalize the playing field, transgender athletes are being unethically coerced into adopting medical practices that do not achieve the desired outcome.Summing up, the researchers concluded that ‘because different sports differ vastly in terms of physiological determinants of success - which may create different safety considerations and retained performance advantages - universal guidelines for transgender athletes in sport should be abandoned for a system in which each individual sports federation evaluates their own conditions for inclusivity, fairness and safety’. Given the profound implications for women’s sport, this is an area of research that we will continue to pay keen attention to. In the meantime, we would be interested to hear what our readers have to say on this topic. You can contact the editor via email: editor@sportsperformancebulletin.com

References

- Br J Nutr. 2017;118(10):858–866

- Appl Physiol. 2000;89:81–8

- Am J Occup Ther. 2019;73(2):1–9

- J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1999;29:116–26

- J Strength Cond Res. 2018;32(11):3070–9

- Sports Med. 1984;1(2):87–9

- J Appl Physiol. 1964;19:268–274

- Physiology (Bethesda). 2015 Jan; 30(1):30-9

- Endocr Rev. 2018 Oct 1; 39(5):803-829

- Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2018 Jan 1; 13(1):2-8

- J Sport Sci Med. 2010;9(2):214–23

- Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2018;13(4):530–535

- IOC consensus meeting on sex reassignment and hyperandrogenism. 2015. stillmed.olympic.org/Documents/Commissions_PDFfiles/Medical_commission/2015-11_ioc_consensus_meeting_on_sex_reassignment_and_hyperandrogenism-en.pdf. Accessed 22 Feb 2021

- Sports Med. 2021; 51(2): 199–214

- Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006 Dec; 291(6):E1325-32

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.