You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Post-activation potentiation: power your way to a new PB!

Tom Whipple explains the relatively unknown concept of ‘post-activation potentiation’ (PAP), why it can benefit endurance athletes, and how to integrate PAP training into an endurance program

Post-activation potentiation (PAP) is the phenomenon by which an athlete’s power can be improved following moderate to high intensity muscle contractions. The method used to induce PAP is known as ‘complex training’, and involves bookending two complimentary exercises around a recovery period. A typical example would involve coupling a set of barbell back squats with a 60-meter sprint. If the squat intensity and rest interval are programmed correctly, the sprint speed will be enhanced relative to a non-potentiated trial. Complex training has been a historical staple in the development of power athletes, and its role in improving endurance performance is expanding.How does PAP work?

Scientists have proposed several mechanisms; some of the more plausible include enhanced psychological arousal, modulation of effort perception, increased muscle cell recruitment, increased blood flow, changes in muscle cell architecture, and improved binding of muscle proteins through a mechanism known as ‘myosin RLC phosphorylation’.What complex training exercises work best?

Most of the training studies to date have utilised traditional strength exercises like squats, cleans, or bench presses to potentiate jump or sprint performance. Importantly, the first exercise must be similar in action to the second. A squat would be a safe bet to precede a jump; the bench press would likely improve an explosive push-up. Examples of complex exercise pairs include:- Squat variety → counter jump, vertical jump

- Bench press → explosive push-up, medicine ball chest pass

- Deadlift → sprint, horizontal jump

- Deadlift→ kettlebell swing

- Barbell row→ rowing ergometer, rowing

- Split squat→ bicycle ergometer, cycling, running

A key principle in complex training: prioritise load and tension in the first exercise, and the rate of force development (or speed) in the second exercise.

What protocols work best?

One to five priming sets of less than 5 repetitions per set have been successful in inducing potentiation. Conversely, sets of more than 5 reps are likely to induce a level of fatigue that will dampen rather than boost power. Also, one set of potentiating exercise may be sufficient for multiple sets of power exercises. For example: 1 set of deadlift reps @ 85% 1 RM followed by a recovery Interval can then be followed by 3 sets of 3 rep of counter jumps.The rest time between the first and second exercise must be long enough to allow most or all fatigue of the first exercise to resolve - yet be short enough to take advantage of the potentiation window, which last for around 20 minutes. Experience and training status, as well as the intensity and volume of the potentiating exercise, are relevant considerations. In general however, 3-12 minutes appears to be range that works best for most athletes.

In one recent study of strength trained males, researchers investigated whether athletes could effectively determine their optimal recovery interval between a 5RM back squat and a vertical jump(1). The athletes were tested under two conditions:

- A four minute fixed rest interval (4FRI).

- Self-selected rest interval (SSRI) where athletes were asked to rest until “they felt fully recovered and able to exercise at maximal intensity”.

The training status and strength of an athlete may be the largest determinants of whether performance in the second exercise is improved. Well trained athletes are capable of recruiting more muscle cells and are more fatigue resistant; as such, PAP should be considered an advanced training method and reserved for athletes that have achieved high levels of strength.

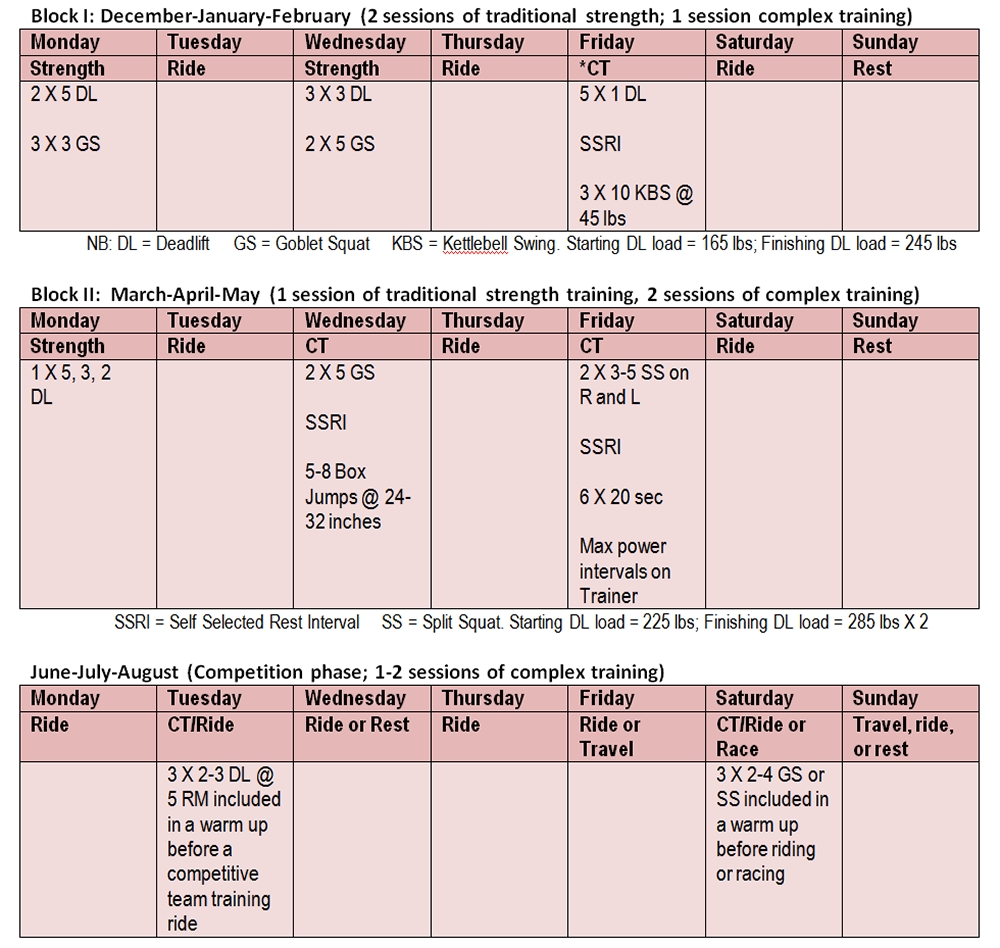

Table 1: Examples of complex training sessions

Does PAP improve endurance?

Although complex training and the expression of PAP is a scientifically proven technique for improving power, what is less well known is that it may also improve an athlete’s fatigue resistance. A 2014 study evaluated the effect of PAP on repeated sprint performance in professional Rugby Union players. Four minutes after performing back squats (using 90% of 1RM), ten males performed 7 X 30-meter sprints, separated by 25 seconds. They also performed the sprints without the priming. The results demonstrated that sprints 5, 6, and 7 were significantly faster and the fatigue rate was lower at both the 10 and 30 meter distances in the potentiated trial(2).Can PAP be used to improve race performance?

A 2012 study investigated rowing time trial performance under two different warm-up conditions (potentiated versus normal warm-up) in ten national class oarsmen. The potentiated trial consisted of five sets of 5 isometric contractions (2 seconds submaximal, 3 seconds maximal) with a 15-second recovery between sets. The rowers elicited these contractions by ‘pulling’ on a fixed ergometer handle, creating tension in their rowing specific posture. A 1,000 meter ergometer time trial was performed after each warm-up on separate days and performance data was collected every 100 meters. The potentiated condition resulted in a slightly better performance as the overall finishing time was reduced by 0.8%. This improvement was brought about by increases in mean power and stroke rate over the first 500 meters(3).Another study featuring trained cyclists, who used four sets of 5RM leg presses with a 10-minute recovery period to potentiate a 20km time trial. Results were an impressive 6.1% reduction in overall finishing time. Even better, the PAP trial provided the cyclists with a ‘free’ return on investment, as their power was increased without altering their perception of effort or pacing strategy(4).

Is PAP training limited to short-term increases in power?

No. Studies have demonstrated that long-term complex training leads to improvements in both strength and power that are at least as effective as stand-alone strength or plyometric training protocols(5). Therefore, complex training can be an efficient training method, simultaneously addressing both strength and power development.Using PAP in training and competition

Complex training may be used during a base (general), or competitive phase of the training year. However, in order for your power to be enhanced using complex training, you must first develop a high level of strength; and consequently, the ability to stabilise and move effectively in fundamental movement patterns. As the old saying goes, “You can’t shoot a canon from a canoe”. If you are a novice or recreational athlete, work toward achieving a deadlift or back squat with 1.5-2.0 times your body weight before considering complex training.Case study: PAP training in action

What follows is a case example of a 21 year old competitive cyclist with previous season results in a 40K TT series of 61:30, 60:48, 62:15. For three previous years John had had worked in the weight room during the winter (December, January, February) but discontinued all gym work during the spring and summer cycling seasons. Although he had achieved a personal best 1RM deadlift of 260 pounds at a body weight of 155 pounds, he felt as though he lost a considerable degree of strength and bike power throughout the season. His plans for the upcoming year were to maintain strength training throughout the entire season, and break the elusive 60 minute barrier for the 40km time trial. His new training structure – which now included complex training - was as follows:

The season concluded with new personal bests in the deadlift (285 lbs for 2 reps in June) and 40km time-trial times of 58:30, 57:42, and 56:10 in June, July, and August, respectively.

Key learning points

- *PAP is the term describing short term increases in power following the performance of moderate or high intensity muscle contractions. The method of inducing PAP is known as complex training.

- *Complex training is an advanced tactic that involves pairing two similar exercises around a rest period. The first exercise must develop near maximal force so the power of the second exercise is enhanced.

- *Self-selected rest intervals between 3-12 minutes between exercises appear optimal.

- *Consider implementing complex training into your programming AFTER you have achieved a 1RM back squat or deadlift of equal to or more than 1.5-2.0 times your bodyweight.

- *Complex training may be performed throughout the year in either non-competitive (base) or competitive seasons.

- *Potentiating exercise protocols typically involve 1-5 sets of less than 5 repetitions. The goal is to facilitate your neuromuscular system; avoid fatigue!

- *The intensity range of the potentiating exercise should be approximately 85% of your 1RM.

- *The PAP phenomenon can be used to increase power in both training and competitive situations.

- *Complex training sessions are typically scheduled 1-3 times per week during base or building cycles. Even lower frequencies can be useful for retaining strength and power during competitive seasons.

- J Strength Cond Res 2018 Feb; Epub ahead or print

- J Sports Med Phys Fit. 2014 Apr;54(2):238-43

- J Strength Cond Res 2012 Dec; 26(12):3326-3334

- J Strength Cond Res 2014 Sep;28(9):2513-20

- J Strength Cond Res 2000 Nov;14(4):470-476

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.