You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Strength training loads: time for a more flexible approach

New research suggests a less rigid approach to setting training loads during strength training could provide athletes with greater benefits

In recent years, SPB has highlighted research on the benefits of strength training for athletes in all sports. In a nutshell, these benefits are almost impossible to overstate; not only can stronger muscles help reduce the risk of injury, the gains in strength and power that result are also beneficial to many athletes – even those engaging in sports, which although primarily endurance in nature, require occasional bursts of power. In addition, more recent studies have demonstrated that strength training can significantly boost muscle efficiency – more technically known as ‘muscle economy’ (see this article for a more in-depth article on economy and how to improve it)(1-5).Fixing your strength-training load

For many decades, traditional ‘fixed-loading’ strength training programs based upon the individual's strength limitation - usually known as the 1RM (one repetition maximum, the highest weight that allows the athlete to complete one repetition using good form) – has been recommended for optimum gains in strength. Briefly, the working load of a fixed-loading method, such as the training intensity and volume, is designed and fixed before the training gets started, where the name ‘fixed-loading’ of the traditional strength training comes from. For example, an athlete with a 1RM of 80kgs for the squat might be prescribed a program of 3 sets x 10 reps at 80% of 1RM (ie using a fixed loading of 64kgs). As training progresses of course this fixed-loading method needs to be performed with an accurate estimation of the supercompensation to achieve effective progress – ie as strength increases, reassessment of 1RM takes place, with adjustments to the fixed loads prescribed in the strength program.Is fixed loading best?

For many, many years, the fixed-loading method has been considered as the gold-standard strategy for strength training, and with good reason; research shows that fixed-loading strength training has been successfully applied in a large number of different sports and among athletes with ranges of abilities(6,7). But is it actually the best strategy? Could there be even more effective ways to set the optimum loading when strength training?These are reasonable questions because while effective, the fixed-loading method also has some disadvantages. For instance, due to daily fluctuations in biological rhythms (principally the circadian rhythm – see this article for a fuller discussion), strength levels can vary by around 10-20% during the day, with highest levels normally occurring late afternoon/early evening and lowest levels in the early hours of the morning(8). In addition, other factors can also affect the strength performance, including sleep levels, warm-up programs, and sports supplements intake, all of which make it difficult to set a perfectly-judged predetermined load(9-11). Consequently, these uncertainties in training load may result in overtraining or inadequate training for the athlete, leading to less than optimum gains.

Other loading methods

To try and improve on the fixed-loading approach, a flexible and adjustable strength training method - known as the ‘auto-regulation’ method – has been developed as an alternative. This method aims to monitor and evaluate whether the working load is reasonable according to the specific performance of athletes at that particular time – ie in accord with each athlete’s real-time conditions. The auto-regulation approach can be executed in three distant ways:- Autoregulatory Progressive Resistance Exercise (APRE) - This is a program that is regulated (and adjusted) on the number of completed reps. The APRE program requires athletes to determine the training load (weight) of the first and the second sets in advance, and then adjust the training weight of the fourth set according to the completed reps of the third set. If the third set's completed reps are more than the target reps, the weight is increased. Otherwise, the weight is reduced.

- The Rating of Perceived Exertion program (RPE) – In this program, the load is regulated using various RPE measuring scales. Regardless of which perceived exertion scale is used, a higher score indicates more difficulty in finishing one rep. For example, using the 1-10 scale, an RPE of 9 means an arduous attempt but still one more rep can be done, while an RPE of 10 means extremely hard and another rep is impossible. If a set is completed with a low RPE, the load is adjusted upwards. But if the RPE is in the 9 or 10 region, the load in the next set is adjusted downwards.

- The Velocity-Based Training (VBT) - This is a program regulated based on the movement speed during the training. This training program highly relies on speed detector, and linear position sensors or wearable devices to monitor athletes' movement and provide feedback. Movement velocity is important since research shows that speeds below 0.5 metres per second are most effective for developing maximum strength. Research shows that for maximum strength and power, movement velocities of the loaded limb should lie somewhere between 38% and 75% of maximum limb velocity(12). Therefore, using this approach, if the movement speed exceeds the velocity range, the load is increased; if it falls below this range, load is reduced or training terminated.

Which is best?

In theory at least, auto-regulation strength training, which adapts to the ability of the athlete on that day, should provide more optimal loading and therefore superior gains compared to fixed-load strength training. However, the evidence to date on this topic has been rather mixed, with some studies showing superior results of auto-regulation training compared to fixed weight(13,14), while others have shown no significant benefits(15,16). But now a brand new meta-review study (a study that pools and analyzes all the previous data on a topic) has been carried out into this topic and has come up with definitive conclusions(17).Published in the journal Frontiers in Physiology, this study pooled the data from eight related studies published between 2010 and 2020, with a total of 166 subjects including division one college players and athletes with at least one full year’s training history, and interventions ranging from five to ten weeks. Three of the studies used the APRE program, two used the RPE program, and three used the VBT program. Meanwhile, the control groups used various fixed-loading programs – ie pre-prescribed based on measures of 1RM. As the 1RM was tested for squat and bench press in the fixed-loading studies, the researchers decided to compare the outcomes for squat and bench press strength between the two approaches – ie between fixed and auto-regulation approaches.

What they found

When the data was analyzed, the key findings to emerge were as follows:- The auto-regulation method of setting loads during strength training was more significantly more effective than the fixed-loading method for developing maximum strength.

- Both squat and bench performance significantly benefitted from the auto-regulation approach, with the greatest effect seen for squats.

- The auto-regulation approach was shown to deliver significant strength improvement within eight weeks or less. However, it lost its advantage over fixed-weight loading when used for eight weeks or more.

- Of the three auto-regulation approaches, the APRE was the most effective training program – ie where athletes determine the training load (weight) of the first and the second sets in advance, and then adjust the training weight of the fourth set according to the completed reps of the third set.

Practical implications

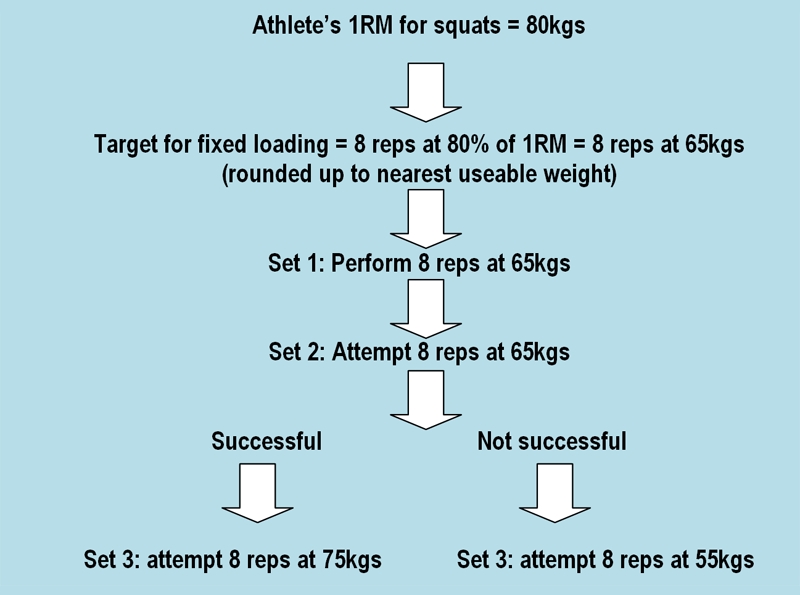

These findings suggest that using an auto-regulation approach rather than a fixed-loading approach when training could offer significant advantages. In particular, using the APRE program seems to offer the most benefits. This is perhaps because it’s the simplest method to apply and doesn’t rely on subjective feelings (RPE method) or complicated equipment (velocity method). Athletes wishing to try the APRE method for setting loads can easily adapt it to lower set counts. So for example, instead of setting the training load (weight) of the first and the second sets in advance, and then adjusting the training weight of the fourth set according to the completed reps of the third set, simply set the load for the first set (according to a % of your 1RM) then adjust the training weight of the third set according to the completed reps of the second set (see figure 1).Figure 1: Example of the APRE approach for squats adapted to three sets

This example assumes the athlete’s 1RM for squats is 80kgs and athlete wishes to work to 80% of 1RM.

Although the data showing the APRE method was more effective was limited to squats and bench presses, there’s no reason why it shouldn’t also be applied to other large compound exercises such as pull ups, dips, lunges etc. Interestingly, over longer periods of time (8+ weeks), the APRE method, while still effective at building strength, was actually no more effective than the traditional fixed-loading method. This suggests that athletes trialling the APRE method should periodize its use – eg use it for say six weeks then revert to fixed loading for a few weeks before re-introducing APRE for another six weeks.

References

- J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2021 Mar 17;6(1):29.

- J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 1991 Sep; 31(3):345-50

- J Physiol. 2008 Jan 1; 586(1):35-44

- Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2006 Oct;31(5):530-40

- Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2002 Oct;12(5):288-95

- J Strength Cond Res. 2003 Feb; 17(1):82-7

- Eur J Sport Sci. 2013; 13(5):445-51

- Int J Sports Med. 2004 Jan;25(1):14-9

- Res Q Exerc Sport. 2020 Oct 21; ():1-8

- Res Sports Med. 2017 Jan-Mar; 25(1):78-90

- Eur J Appl Physiol. 2014 Aug; 114(8):1749-55

- J Hum Kinet. 2011 Jun; 28():33-44

- Mann J. B. (2011). A Programming Comparison: The APRE vs. Linear Periodization in Short Term Periods. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Graham T, Cleather DJ

- J Strength Cond Res. 2019 Apr 17

- Front Physiol. 2018; 9():247

- Fisher D. L. (2016). Velocity-Based Training as a Method of Auto-Regulation in Collegiate Athletes. Bellingham, WA: WWU Graduate School Collection

- Front Physiol. 2021 Mar 12;12:651112

Related Files

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.