Cool garments: good for hot performances?

Can hi-tech fabrics improve cooling and performance when the heat is on? SPB looks at the evidence and latest research

Most athletes are familiar with technical clothing designed to keep you warm and dry. In the last decade or so however, a new breed of garments using so-called ‘cooling fabrics’ has appeared on the market. These use various technologies to try and actively cool the skin - examples include aluminium-based dots embedded into the fabric to conduct heat away from the skin, and embedded hydrophilic (water-attracting) rings inside a moisture wicking fabric to create a cooling effect when triggered by sweat. But how effective are these cooling fabrics for actually enhancing performance?In theory at least, there should be benefits when using these fabrics. In warm or hot environments, clothing acts as a barrier to maintaining thermal balance by inhibiting evaporative and convective cooling – important routes to shedding excess heat. Clothing construction, fit, and fabric are all critical influences on the amount of sweat absorbed from the skin and transported throughout the clothing. If these factors can be manipulated to help transport sweat away from the skin and enhance evaporative cooling, heat losses from an exercising body should be greater, thus helping to maintain lower (and more desirable) core temperatures.

Early research

That’s the theory, but what does the research say? A comprehensive 2013 review study (a study that pools data from previous studies) concluded that the majority of the research analyzing advertised synthetic fabrics has shown ‘no difference in thermoregulation or clothing comfort while exercising in those fabrics in the heat compared to natural fabrics’(1). One eloquent example of this early research was carried out by US scientists(2). They investigated whether temperature regulation was improved during exercise in moderate heat by the use of clothing constructed from fabric that was purported to promote sweat evaporation compared with traditional fabrics.In this study, eight well-trained, fully hydrated males performed three exercise bouts on three separate occasions wearing garments made from two different materials along with a control condition. These were as follows:

- A specially designed evaporative polyester fabric (SYN) designed to enhance cooling

- A traditional cotton fabric (COT)

- Control condition, dressed semi-nude (ie no clothing barrier to inhibit sweat evaporation)

The results of the trials showed that although the average skin temperatures recorded during pre-exercise rest were lower in the semi-nude trial compared with SYN and COT, there were absolutely no significant differences in mean body temperature, rectal (core)temperature, or mean skin temperature observed during or after the exercise sessions. In addition, no differences in oxygen uptake or heart rates were seen and no differences in perceptions of comfort were observed. In short, the hi-tech fabric in this test produced absolutely no cooling benefits whatsoever.

Later research

Later research supported these findings. In a 2015 study by Canadian scientists, twenty trained athletes were divided into two groups(3). Both groups completed an indoor ride to exhaustion at 85% of their maximum power (hard!) on an exercise bike while wearing an outfit consisting of a fitted long-sleeved shirt and full trousers. However, one group wore a cooling fabric claimed to have superior cooling properties and evaporative characteristics (a Nylon/Spandex mix manufactured by Lamour Hosiery) while the other group wore garments made of a synthetic control fabric with no claimed cooling properties.The results showed that the ‘cooling fabric’ offered no significant advantages to the athletes who wore garments made from it. Their riding times to exhaustion were no longer, and their skin temperatures, heart and breathing rates and perceived exertion levels were no different either (you would expect all these measures to be lower if there had been an actual cooling effect). So like the earlier research, this study once again drew a blank.

Bogus claims?

At this point, you might reasonably assume that many of these ‘cooling garments’ claims are bogus. However, because different cooling garments employ different technologies, they can’t be all dismissed out of hand, but the studies cited above do suggest that buyers shouldn’t automatically assume that all cooling garments will live up to the manufacturers’ promises! Of course, like all technologies, clothing technology does not stand still. This means that just because earlier clothing technology might have failed to produce cooling benefits in the past, better materials and designs could reap benefits going forward. But is there any evidence for this?A 2017 study suggested that perhaps cooling clothing IS becoming technologically better at delivering benefits(4). In this study, researchers investigated the influence of clothing on thermoregulation and comfort during exercise in the heat, and whether sports textiles made from synthetic fibers have superior properties for keeping wearers cooler, drier, and more comfortable compared with natural fibers.

Eight male collegiate athletes performed three trials on three separate occasions, each consisting of a 45-minute treadmill run at 60% of maximal oxygen uptake (easy-moderate effort) in an environmental chamber where the temperature was held at 32C (90F). In each trial, the athletes wore T-shirts during exercise made of one of three different fibers:

- 100% cotton

- A blend of natural fibers (50/50% cotton/soybean)

- A synthetic ‘cooling’ fiber (100% polyester) with mesh loops to facilitate ventilation through the clothing

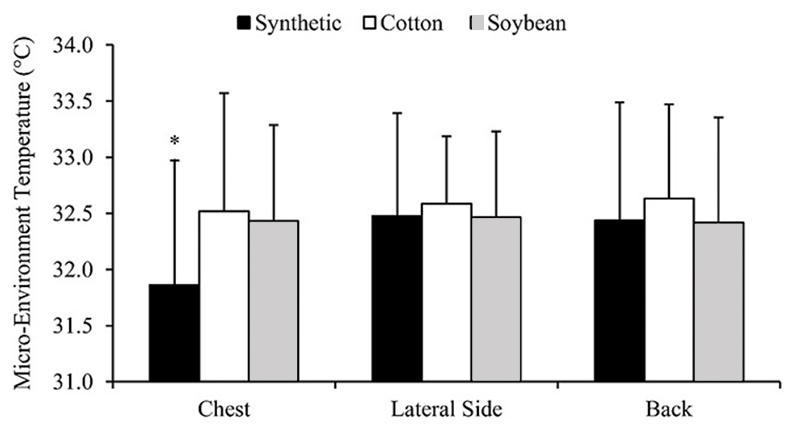

Figure 1: T-shirt material and microenvironment temperatures(4)

The cotton/soybean and synthetic fabrics resulted in a trend to lower skin temperatures around the lateral side and back, but not enough to be statistically meaningful. However, when it came to the skin temperature around the chest area, the synthetic cooling fabric produced a very significant effect (ie reduced temperature.

Latest findings

Following the above study, research on cooling garments seemed to taper off somewhat but a brand new study just published suggests that garment technology may have moved on even further in the interim period. In a study, which appears in the journal Frontiers in Sport and Active Living, researchers examined the effects of different fabric types on the 20-km cycling time trial performance of competitive cyclists and triathletes(5). What’s particularly interesting in this study is that the scientists didn’t just look at the physiological effects of each clothing type, they also sought to discover if there was a direct effect on exercise performance.Fifteen well-trained cyclists and triathletes performed two 20km time trials on two separate occasions. Both trials were carried out under identical ambient laboratory conditions (24C (75F) and 17% relative humidity) with a simulated wind speed of 3 meters per second. However, what the athletes wore during each time trial varied:

- A 100% cotton long-sleeved shirted with a snowflake mesh bi-layer construction and full-length leggings using the same weave construction.

- The same shirt/leggings design and identical weave but constructed from a synthetic blend of 60% polyester and 40% nylon – the cooling garment (made by ‘Under Armour’, Baltimore, MD, USA)

Results

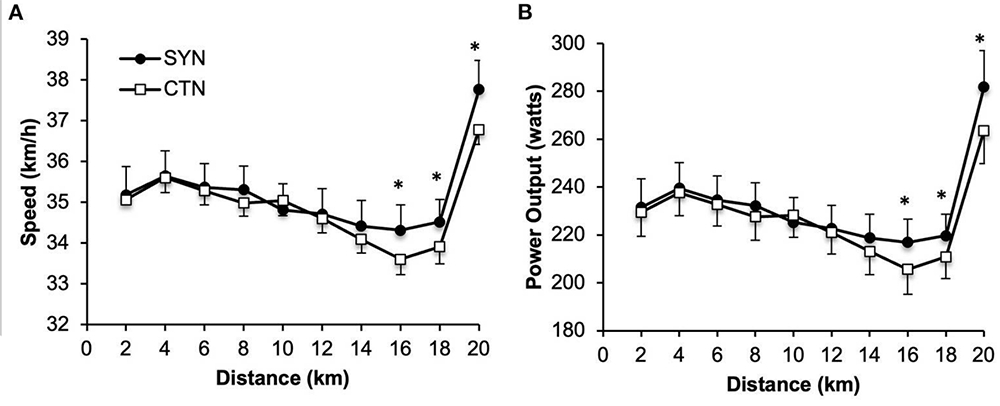

The key findings were as follows:- Participants maintained a significantly higher cycling speed (+0.98kmh) and power output +18.4 watts) over the last 6kms of the 20km time trial when they wore the synthetic (cooling) garments (see figure 2).

- Consequently, 20km time trial times were significantly reduced by around 15.7 seconds (+0.8%) when wearing the synthetic garments compared to the cotton trials.

- Bizarrely however, the increase in time trial performance that was clearly evident could not be explained by lower core temperatures, rates of sweating, ratings of perceived exertion and/or the athletes’ cardiovascular responses during exercise, as all of these factors were similar between trials.

- The better performances during the synthetic trials however were accompanied by significantly lower mean skin temperatures (around 1C lower) and more favorable ratings of perceived clothing comfort and thermal sensations during exercise.

Figure 2: Speed and power output during the 20km time trial(5)

In the later stages of the time trial, both speed (A) and power output (B) was significantly higher when the synthetic garments were worn compared to cotton.

In a nutshell, wearing the synthetic ‘cooling garments’ didn’t really impact on key aspects of heat regulation. However, what they did do was to lower the ambient temperatures around the skin and make the athletes feel more comfortable, which seems to have enabled them to perform better during the time trials.

Conclusions and practical advice

As we head into summer (here in the northern hemisphere), what should athletes make of these findings, and how do they inform clothing choice? The first thing to say is that when it comes to the fundamentals of heat regulation during exercise such as core temperature and sweating rate, there’s little evidence that these hi-tech cooling garments offer a significant advantage over tradition fabrics such as cotton. However, in recent years, some of the newer fabrics do seem to help promote cooler microenvironments close to the skin, which in turn improves comfort and perceived effort. The psychological advantage of improved comfort is not to be sniffed at, especially as the brain and perceived effort play a major role in exercise performance. This improved comfort may in turn allow higher work rates to be sustained, particularly during longer efforts in very warm/hot conditions.The downside of course is cost; compared to conventional fabrics such as cotton, the more technologically advanced garments come at a hefty price premium. Also, there’s no guarantee that a particular garment will definitely lower local skin temperature; it’s a ‘case of try it and see’ (a more effective garment will likely feel noticeably more comfortable). Don’t forget too that even conventional fabrics differ in their ability to keep you cool, and some can be quite good; an open weave, loose fitting plain white cotton T-shirt for example can promote decent air movement and has excellent radiant heat reflection properties. While not suitable for cyclists (tight fitting clothing is best), it could be a reasonable choice for runners on a budget. Another thing to remember is that there are other ways of reducing thermal sensations – not least drinking plenty of cold drinks during exercise and using water sprays/mists for extra evaporative heat loss!

References

- Sports Med. 2013 Aug;43(8):695-706

- Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001 Dec;33(12):2124-30

- Physiol Rep. 2015 Aug;3(8). pii: e12505

- J Strength Cond Res. 2017 Dec;31(12):3435-3443

- Front Sports Act Living. 2022 Jan 5;3:735923

You need to be logged in to continue reading.

Please register for limited access or take a 30-day risk-free trial of Sports Performance Bulletin to experience the full benefits of a subscription. TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.