You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles. For unlimited access take a risk-free trial

Brain and pacing: why ignoring the clock might be good for a PB

In a previous article for Sports Performance Bulletin, Richard Lovett looked at the physiology of pacing and what this means for runners for seeking a PB. In this article, Richard discusses how your state of mind can play a major role in determining your ideal pacing strategy

When the horn sounded for the start of the 2017 Sportisimo Prague Half Marathon, Joyciline Jepkosgei went out hard. So hard in fact that she wound up running what most of us would consider a dismal set of positive splits. In percentage terms, her speeds for each successive 1km were 100.0% (the fastest 1000m pace) 98.0%, 95.7%, 94.2%, and (for the final 1.0975 km), 94.7% (see figure 1). That’s not what most of us would want - until you look at the raw numbersHer first two splits over 10kms added up to a 30:04, breaking Paula Radcliffe’s 14-year-old 10km road-race mark by 17 seconds! The next 5kms yielded a 15km world record (this one by 37 sec) and the fourth was good enough to chop 15 seconds off the 20km mark. All of it en route to the fastest women’s half-marathon in history (64:52).

In a previous article we discussed the science of pacing, which generally favors either even pacing or what we can call ‘U-shaped’ pacing (usually a very wide and shallow U), in which you start fast, settle, then finish fastSports Performance Bulletin Apr 2017. (364)3-8. But the research also found that - at least for non-professional runners - breakthroughs sometimes come from forgetting the rules and simply throwing caution to the wind, which appears to be what Jepkosgei did. Would her half-marathon time have been even faster had she paced it more traditionally? Who knows? But her kamikaze approach netted not only the half-marathon record, but three extra records along the way. Sometimes, it appears, exercise science takes a backseat to psychology!

Figure 1: Joyciline Jepkosgei’s splits For the 5km

Fooling the brain

Part of our pacing psychology is probably subconscious. The world famous South African exercise physiologist Professor Tim Noakes has long argued that the sensation we interpret as fatigue doesn’t actually mean our muscles are nearing their absolute limits. Rather, there is a part of the brain he dubs the ‘central governor’ whose job it is to make us feel tired in order to ensure we don’t overtax ourselves badly enough to risk serious damageJ. Experimental Biology 2001. 204 (Pt 18): 3225–3234. In other words, fatigue isn’t the result of muscles hitting their limits—it’s an ‘emotion’ generated by the brain to make sure that complete muscle fatigue never happens.His first inkling of this came when he read an account of the first-ever ascent of Mt. Everest without supplemental oxygenReinhold Messner. Everest: Expedition to the Ultimate (1979). “As we get higher,” Italian climber Reinhold Messner wrote, “it becomes necessary to lie down to recover our breath. Breathing becomes such a strenuous business that we scarcely have strength left to go on.”

It’s easy to see why Messner found breathing to be such an all-consuming task: the summit of Everest has only one-third the amount of oxygen we are accustomed to (see figure 2). But why, Noakes wondered, did the climbers feel so fatigued? Their muscles weren’t doing any more work climbing the last meter than they were in the first.

Figure 2: Diminishing oxygen pressure with increasing altitude

The answer, he concluded, came from the fact that at high altitude, the body is desperately struggling to get enough oxygen into the blood to keep the brain functioning, and the margin for error is so small that even moderately vigorous climbing would cause blood oxygen to dip dangerously. So to save itself, the brain produces a sensation of exhaustion, even when there’s no exercise-based reason for it.

Noakes’ colleague Alan St. Clair Gibson has suggested that evolution may have predisposed the central governor to be quite conservative, thereby ensuring we never completely wear out our muscles. That way, there’s always something left for emergencies, such as the appearance of a lion or pack of hyenas at the end of a grueling day RA Lovett “Running on Empty,” New Scientist March 2004. 42-45.

The upside of this means there might be extra energy to harvest in a race if we can convince our central governor that the other runners (or the clock) are equivalent to a pack of hyenas that will eat us if we falter. Perhaps this is why start-fast strategies sometimes work, even when they would seem to be prescriptions for disaster— the fear of being eaten by the pack (or faltering and embarrassing ourselves) may be all it takes to get the central governor to relax its grip, even if by just a bit.

Ignoring the clock

Alternatively, maybe it’s sometimes possible to fool the brain by ignoring the clock, so the central governor doesn’t know what we’re doing until it’s too late to stop us. This may be how Jepkosgei ran her four-record race. As she herself put it: “I didn’t know even at the finish line. Even now I am surprised about it!” It may even be possible to simulate this in training. Sometimes, when I think a runner is poised for a breakthrough, I tell them to take off their watch in a track workout and let me time them.The first time I tried this was with a female marathoner who usually did mile repeats at about 5:35s. Her first watch-less repeat came in at 5:23. “What did that feel like?” I asked. She shrugged. “Not all that fast. 5:38? But don’t tell me.” Five repeats later, she pronounced the workout “easy,” estimating she’d averaged about 5:36s. Actually, she’d averaged 5:28s, and only once had been slower than 5:30.

Later, when she ran the same workout with her watch, the new pace recurred. The bottom line is that while the central governor may be powerful, if you can find a way to fool it, it may allow you a breakthrough. And once convinced that you won’t die at your new quicker pace, it may reset, allowing the ‘new’ to become the norm.

This approach may also help to prevent your training from falling into a rut. Rather than always doing workouts focused on your target race distance, it can be a way to jolt your body out of its routine. Mo Farah’s coach Alberto Salazar explains it in terms of laying the groundwork for what you want to accomplish – rather like constructing a flight of stairs.

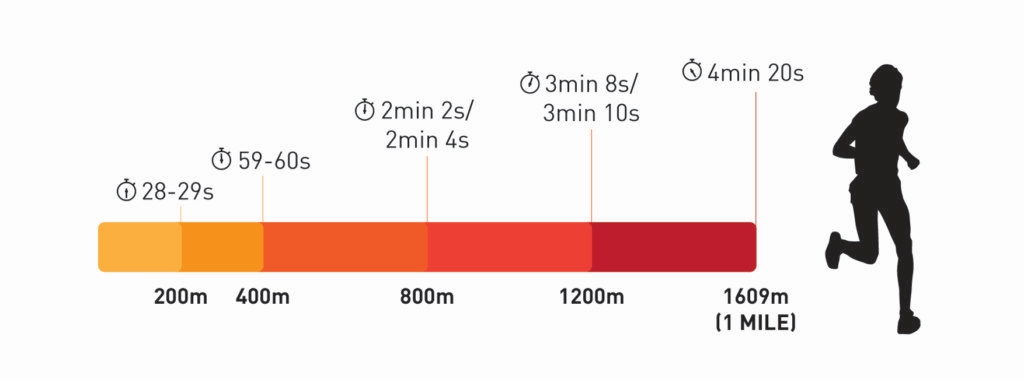

When Salazar was planning on racing 10kms at a 4:25 per mile pace, he needed to run repeat miles at 4:20. But to do that, he needed to be able to run 1,200 meters in about 3:08 to 3:10. That required a background of 800-metre runs in 2:02 to 2:04, which in turn required him to be comfortable with 59 to 60-second quarters. Those quarters in turn needed to be based on the ability to run 28 to 29-second 200 metres (see figure 3). As Salazar explainsAlberto Salazar’s Guide to Road Racing (Ragged Mountain Press: Camden, ME) 2003, 66-67 “Without the 200s, I couldn’t have built the speed for the quarters, 800 metres, 1,200 metres or miles. And 4mins:25 second miles during the 10K would have been impossible. The short intervals provided a base that supported the long ones.” Some of that is physiological, but maybe you periodically need to remind the central governor that you are faster than it wants to think.

Figure 3: Breaking down the pacing into fast 200m segments

Yoda running

So far, we’ve talked about the psychology of pacing when things are going well. But what about the opposite situation, where you start a race, and instead of having a breakthrough (or even running at your normal energy level), you’re feeling sluggish and wondering if you’re going too fast?It’s possible, of course, that this feeling is correct. Perhaps you’re coming down with an illness, over-stressed at work, or not properly rested. Perhaps your race plan wasn’t realistic for your present level of fitness. But before you throw in the towel, remember the old adage about doing the race one kilometer at a time. Or, if at that moment a kilometer seems incomprehensibly long, one block, or even one telephone pole, at a time!

Jeff Simons, a sports psychologist at California State University believes that endurance athletes often focus too much on thinking about the beginning or end of the race and not on the middle - even though the middle is often the bulk of it. “One of the ways to get through a plateau is to really think during the middle of your race,” he says.

Faulder Colby, a clinical psychologist and marathon runner from Washington, refers to a famous scene in the second Star Wars movie, in which Luke Skywalker is whining about his training, telling Jedi Master Yoda that he’s trying as hard as he can to accomplish the assigned task. Yoda cuts him off. “Do or do not,” he says. “There is no try.”

This sounds like the worst possible kind of high-pressure coaching, but some sports psychologists believe there’s more than an element of truth in this approach. That’s because ‘trying’ requires mental energy. ‘Doing’ however replaces fear and frazzled efforts with focused action. This is what is what is often referred to as ‘being in the zone’ - a mental state where you’re performing without thinking about success or failure.

Most, if not all, sports have such a stateOnline J. Sport Psychology 1999. (3)21-30, the with the resulting state of mind sometimes also described as ‘flow’. According to the literature, this state of mind, or being in the zone, is characterised by eight factors (see figure 4)Csikzentmihalyi, M. (1990). “Flow: The psychology of optimal experience”. New York: Harper & Rowe.:

- *Well-understood goals

- *Reasonable expectations

- *Merger of action and awareness

- *Total concentration on task at hand

- *The feeling that you are (or at least can be) in control

- *Immersion so deep you lose your normal sense of self-consciousness

- *Altered sense of time

- *Doing it simply for the sensation of doing it

Figure 4: Eight characteristics of ‘flow’

Another useful analogy is to think of the difference between watching a football game and only caring about the final score. The fun part of watching the game is the experience of living through it – you can always read the score in the paper the next day! In other words, when we race, we ourselves are the game. What’s needed is to shift focus from thinking only about the outcome, to the drama and experience of the event itself. This approach represents a shift from outcome-oriented thinking to mastery-oriented thinking - ie a realisation that you are the runner, not the clock.

In terms of racing, there’s evidence that this approach really can be useful. A 2003 study of British dance students found that those who had followed performance-oriented programs were more anxious and perfectionistJ. Dance Med. & Sci. 2003 7(4), 105-114. Those from mastery-oriented programs were more task oriented — this is exactly what you want to be in a race. In other words, if you find yourself feeling sluggish or wondering if you’re going too fast, try not to worry about the outcome. Concentrate on the moment, assessing how your body is performing (assisted by the eight principles of flow), and do the race, one telephone pole at a time.

CASE STUDY: Steve Moneghetti

Australian Steve Moneghetti was one of the great marathoners of his time. Moneghetti started out as a 10,000-metre runner and finished fifth in that event at the 1986 Commonwealth Games. He ran his first marathon at the same meet, winning the bronze medal. Moneghetti’s first marathon victory was in Berlin in 1990, which he won in the time of 2:08:16, coming only a couple of weeks after winning the Great North Run in 1:00:34. In 1991 he set the course record of 40:03 for Sydney’s iconic 14km City-2-Surf race (which still stands). In 1994 he won the Tokyo Marathon and the marathon at the Commonwealth Games.In 1997, Moneghetti entered the World Championships, in Athens, Greece. He’d never won a medal in the Worlds, nor had he ever run well in heat. But as the race start drew near, it was obvious it was going to be a scorcher! Worse, on a training run a week before, he’d been clipped by a motor scooter that had bruised his Achilles tendon. Some people might have written it off, but Moneghetti was already in Athens, had trained hard, and was thinking of retiring afterwards. So he began his warm-up routine. Jeff Simons (sports psychologist) got the story firsthand from Moneghetti. During this warm up apparently, Moneghetti was ‘feeling like crap’. Nevertheless, he started – only to be promptly dumped by the lead pack.

It was at this point that Moneghetti decided to let go of ‘what was supposed to happen’, instead deciding to simply settle into a rhythm and accomplish whatever the day would allow – even if that was just placing somewhere in the top 20. However, about ten miles into the race, he learned that he was starting to catch up with the leaders. Gradually, he moved up the field, until, somewhere around mile 23, he had moved up all the way to fifth position. By the end of the race, Moneghetti had moved into third position, bagging a bronze medal. As Simons explained, He wound up with a bronze - his only world medal in a long, illustrious career. The fact that he got that medal on a ‘crap’ day was almost certainly partly due to his ability to adjust his pacing expectations!

Newsletter Sign Up

Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.